How Blender won over the design world

For decades, Blender—the open-source 3D software tool—had a quirk that distinguished it from other animation software on the market. Instead of clicking to select with the mouse or trackpad’s left button, it required users to right-click selections. It was a small but strange defiance of usability norms, and it was illustrative of Blender’s unconventional approach to design software.

For years after launching in 1994, Blender was considered an under-the-radar tool. Its challenging UX and open-source nature meant it was used primarily by designers and animators who had no money to spend on five-figure professional 3D software licenses.

Then in 2019, things changed.

Blender rolled out a wholesale redesign, including switching right-select to left-select. It updated its interface to be easier to use and introduced new features that could compete with bigger-budget software packages like Cinema 4D and Autodesk’s Maya. Data from Blender shows that download numbers jumped from tens of thousands of downloads per month to nearly 1 million after the relaunch, and since then user numbers have continued to grow.

Today, Blender has become a go-to tool for creatives, and one of the most requested tools across current design jobs listings. According to data from Fast Company’s 2025 Design Jobs report, requests for expertise in Blender jumped 88% in the past year, and it’s the most mentioned piece of software in graphic design job listings.

The updates made six years ago have had ripple effects on Blender’s business and relevance in the creative world. “2019 was the moment when the Blender Big Bang started,” says Francesco Siddi, who serves as COO at the Blender Foundation and producer at Blender Studio. “It was really a lot of different factors, but you sometimes reach a threshold of usability and accessibility combined with a bunch of other factors, and that’s when things start to roll.”

The Swiss Army knife of software

In recent years, Blender has transformed from niche software into a Swiss Army knife of digital creation that is invading designers’ desktops everywhere. There are motion graphics designers who put After Effects on the side and work in 3D space using Blender’s real-time rendering, which allows for instant visualization of scenes. Concept and traditional artists sketch directly in 2D/3D space using Blender’s Grease Pencil, a powerful 2D paintbrush that allows users to draw, sculpt, and edit 2D elements directly in a 3D environment. Industrial designers prototype with geometry nodes.

Alberto Petronio—a lead designer who worked on yachts and planes before getting into the entertainment market—says he hopes Blender will “completely emancipate” him from Photoshop, “because that software has gone downhill.” Petronio even edits video in Blender rather than using dedicated software. “I know that there is DaVinci Resolve, but I don’t know how to use it. So if I have to cut or revert a video, it’s very easy for me to be in Blender.”

The revolution extends far beyond traditional creative fields. Every year at the Blender Conference, people come from all industries and parts of the world with extraordinary uses for the software, a testament of the flexibility and approachability that has made it so popular. Siddi told me how surprised he was when he discovered doctors simulating proteins with geometry nodes, forensic analysts reconstructing crime scenes from phone footage, and architects designing fire safety elements in buildings. One presenter at the 2022 edition digitally re-created the Beirut explosion of 2020 in extraordinary 3D detail using multiple video sources.

Breaking down the wall

The expansive use cases for Blender were not something the company could have foreseen. For decades, 3D software was considered niche and out of reach for most creatives. Since 1986, when John Lasseter and Ed Catmull launched Pixar as 3D modeling software, 3D software has spawned a constellation of multibillion-dollar industries producing everything from Hollywood hits to console games. But that creative explosion also created barriers that locked out entire communities of creators who didn’t have the money or the resources needed to learn increasingly complex and technical software suites.

Back in the ’90s, it was a professional industry dominated by packages that cost thousands of dollars from companies like Alias and Wavefront running on prohibitively expensive computers by Silicon Graphics. Later, the software got cheaper as production moved to high-end (but barely affordable for most) PCs running packages like Maya or 3ds Max.

Today 3D software demands monthly subscriptions ranging from $200 to $500, pricing out freelancers, students, and artists who might want to experiment with 3D. Luís Cherubini, cofounder of a Tokyo-based 3D outsourcing company, tells me that he started with Blender 17 years ago in Brazil because “most people in Latin America back in the days couldn’t afford the licenses.”

But price was just one part of the adoption equation: Historically 3D software has been really hard to use. The software interfaces remained “very, very complex and disorganized,” Cherubini says. “The learning curve to get started was really big.”

All those packages evolved as specialized tools for large and small animation studios. Each software addressed specific production pipeline stages—modeling, rigging, animation, rendering—requiring teams of specialists. The complexity worked for studios with dedicated departments, like Ford’s serial production factories, but alienated individual designers, 2D artists, conceptual artists, product designers, motion graphics creators, and even tattoo artists who needed broader tool sets without steep learning curves.

Blender wasn’t the exception. For decades, Blender was even more alienating than its competitor tools. It suffered from usability problems until the Blender Foundation—the nonprofit organization that controls its development—committed to radical change at the risk of alienating its tiny but extremely dedicated user base.

Blender’s breakthrough moment

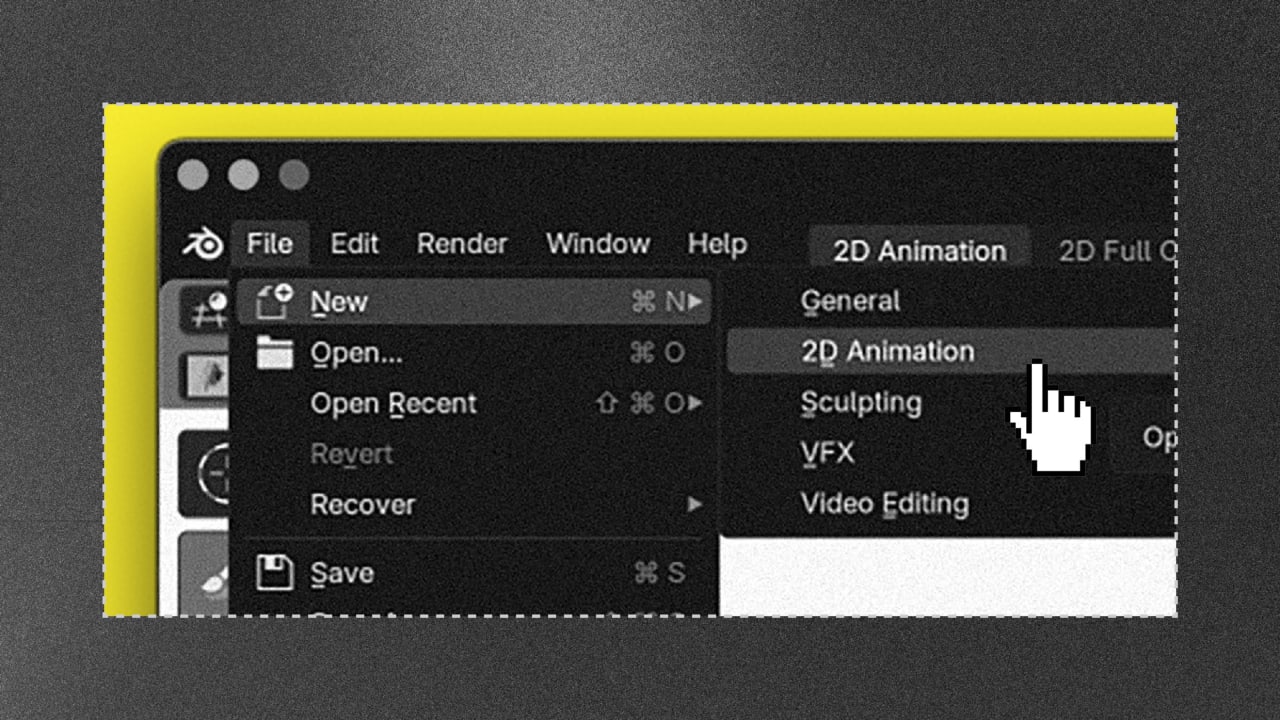

In 2017, Google’s Summer of Code initiative provided funding to Blender for a complete overhaul of its user interface. “They hired two to three programmers in-house in Amsterdam to revamp the software user interface,” Cherubini tells me. “The user interface became more accessible, everything became more user friendly. It was not only about the user interface, it was about the entire user experience.”

The July 2019 release of Blender 2.8 represented a complete reimagining of Blender’s UX. The foundation modernized the viewport system, which Siddi describes as “the space where you spend the majority of your time.” The previous system relied on technology that was 10 to 15 years old. The new viewport—which took over the entire screen rather than being constrained to a small window surrounded by a labyrinth of icons and menus—was redesigned to let users “focus on your artwork rather than distracting UI elements.”

It also enabled real-time visualization and faster iteration, which is crucial for production in general but especially for 2D design, motion graphics work, and concept development. It did so through a visualization system called Eevee, a real-time rendering engine that eliminated lengthy render times and provided instant feedback to your actions in full color, rather than having to work with wireframes.

A tabbed workspace system streamlined navigation. Modern icons and dark themes made the interface more intuitive. The new UI also allowed users to tailor the UX to their specific needs, Petronio tells me. “You can completely restructure your layouts,” he says. “You can completely restructure your shortcuts. It’s very flexible, so it allows a lot of different types of professionals to use it for work.” The customization capability transforms Blender from generic software into personalized creative environments.

This modularity spawned an entire add-on economy, too. Add-ons range from $20 tools to specialized software like Quad Remesher, which costs $160 and optimizes complex 3D models. Some developers release code freely on GitHub while accepting donations. Others create proprietary tools for specific industries.

But there was also a tiny, seemingly inconsequential UI change that was crucial for the Blender revolution: Left-click selection replaced right-click selection. For decades, Blender defied industry standards by using the mouse/trackpad’s right button for selection, creating an immediate barrier for newcomers. As Cherubini points out, this unconventional approach felt “very strange, even for people who had never used a 3D software” because most digital tools reserve left-click for primary actions like selection.

The old method caused practical workflow issues too, as Petronio notes. “While you’re selecting things, you don’t move them accidentally” with left-click. This precision matters when manipulating complex 3D scenes. Like UX expert Jakob Nielsen says: Don’t change an industry-wide UX convention unless your alternative is fundamentally better.

The selection button change allowed users from Photoshop, Illustrator, and other standard tools to transition without reprogramming their muscle memory. This seemingly small update symbolized Blender’s shift from niche tool to accessible platform. The change was a cornerstone of a broader new philosophy: making Blender work with user intuition rather than against it, Siddi says.

The accessibility breakthrough happened because Blender’s developers approached tool design differently than commercial software companies. “When they implement something, they’re not trying to nudge you one way or the other,” Petronio points out. “They just put it in. They’re like, all right, it’s yours now.” This philosophical difference enables users to adapt Blender to their workflows rather than forcing workflow changes.

Daniel Vesterbaek, a freelance 3D generalist, tells me via email that this is one of Blender’s core advantages. The software “never followed the ‘industry standard’ and wasn’t controlled by studios and shareholders. It was built by a bunch of skilled developers who submitted code because they were passionate about the project, not because they wanted their paycheck.”

The Grease Pencil factor

Another important tool that has changed the perception of Blender for 2D artists and designers is Grease Pencil, one of the most attractive tools for newcomers because it basically feels like painting with a Photoshop brush. The tool fundamentally reimagines how artists approach 2D creation by placing it directly within 3D space. It began as a simple annotation tool for making temporary notes in 3D scenes but evolved into a 2D drawing, painting, and animation system that exists natively in Blender’s 3D viewport.

The core innovation of Grease Pencil lies in its unique approach to digital drawing. Unlike traditional 2D software that works on flat canvases, Grease Pencil creates strokes as collections of points positioned in 3D space. These strokes behave like 3D objects—they can be moved, rotated, lit, and even rigged like any other element in a Blender scene. Artists can draw a character from one angle, then move the camera around to view it from different perspectives, or integrate 2D drawings directly with 3D models and lighting.

Users love Grease Pencil because it breaks down the traditional barriers between 2D and 3D workflows. Artists can create traditional frame-by-frame animation, concept art, paintings, illustrations, cutout puppet animation, motion graphics, and storyboards all within the same 3D environment. At any time, you can transform and animate those 2D designs into sophisticated animated graphics adding tools like lighting and cameras. Photoshop and After Effects have tools to add 3D elements, but they feel like an afterthought slapped into their 2D architecture. Grease Pencil takes the opposite approach, adding 2D flexibility and power to a 3D environment in a way that feels natural.

The tool supports pressure-sensitive styluses and offers sophisticated features like onion skinning, vector-based editing, and a comprehensive modifier system that includes noise, build, tint, and other effects. These modifiers allow artists to create complex art without destroying the original artwork, maintaining nondestructive workflows at all times.

This versatility has attracted artists from diverse backgrounds who previously worked in separate software ecosystems. Illustrators can paint directly on 3D surfaces, motion graphics designers can create depth-aware animations, and concept artists can sketch ideas that integrate seamlessly with 3D scenes. The tool’s ability to combine traditional 2D drawing freedom with 3D spatial awareness has made it particularly valuable for stylized animation projects, where artists want to maintain hand-drawn aesthetics while benefiting from 3D camera movements and lighting.

Taking over education

Midge “Mantissa” Sinnaeve—a 3D artist and teacher at the Syntra AB training center in Flanders, Belgium—witnessed the other Blender seismic shift that led to its recent popularity. “It exploded in schools,” says Sinnaeve, who’s been teaching for 15 years and noticed Blender’s popularity surge in the last 5. “Suddenly, it’s everywhere,” he says, noting that students embrace Blender’s Swiss Army knife approach. “You can do 2D animation. You can do video editing. You can do compositing. You can do 3D animation. You can do everything really.” It also helps that the software is free.

Universities worldwide have adopted Blender as primary teaching software, creating talent pools that influence industry implementation. Game studios like Ecosoft, where Petronio worked, “decided to use Blender to save money and to take advantage of the amount of talents that are studying Blender instead of 3ds Max.”

Another unexpected factor that helped popularity was COVID-19. The global pandemic and its lockdowns accelerated adoption as creators gained time at home to experiment. “There was really big growth of the software,” Siddi recalls. “People had time to play with it and they found out that it was actually something fun that they wanted to do. Blender retained a lot of users after that time.”

Social media also amplified Blender’s visibility as artists shared impressive work online. “You get skilled artists who have never used the software before,” Siddi tells me. “They can find their way around. They can make something awesome, show it to the world. And all of a sudden, people think Oh, wow, Blender is a great tool!’”

The transformation reflects deeper changes in digital creation. “The digital natives, kids who start to do content creation nowadays, they know about Blender,” Siddi says. “Everybody knows. So then you at least try it and then you play with it. And Blender is meant to be accessible and playful.” All you need is a computer and an internet connection and you’re ready to go, at any company, anywhere in the world, Sinnaeve says. “I just download it, install it, and I’m good to go. I don’t have to think about licensing. Just having that safety net of knowing that the software is never going to go anywhere really gives me more time to think about what I want to do with it.”

AI control

The flexible power of Blender feels even more appealing in the era of generative art. It’s something the Blender Foundation has been thinking about. “The topic of AI is obviously very hot, and people want to know what Blender is going to do with it,” Siddi says. The foundation is leaning toward creating AI tools that can speed up people’s creative workflows while allowing them to keep control. He says its developers are talking about upscalers (to lower render times), denoisers (to increase quality), voice isolation (for dubbing), and “computer vision-related stuff” to help artists work with external images in an easier way.

These technologies address practical workflow bottlenecks without generating content that might compete with human artistic vision. The foundation will maintain its core philosophy, Siddi says, noting, “Our goal is to make artists be in control. That’s the mantra when you talk about anything, but especially when you talk about AI stuff.”

There is already AI integration through community initiatives. Users employ Blender for synthetic data generation, training AI models with 3D-rendered environments. Others bridge Blender with ComfyUI—an open tool to set up all types of generative AI workflows—feeding 3D scene information to AI rendering nodes.

Siddi highlights Cascadeur as an example of AI assistance that maintains artistic control while improving efficiency. This keyframing tool allows animators to pose characters, then uses motion capture training data to interpolate between poses more naturally than traditional algorithms. “This is something that is already entering more the territory of making people cringe, thinking that this is now taking control away from the artist,” Siddi admits. “But this is a tool that allows animators to pose a character in 3D, then do another pose, and then the AI interpolates.”

The vision extends to contextual AI interfaces that understand user intent without replacing creative decisions. Siddi describes potential VR workflows in which artists could command “Put a tree there” and have the system reference their existing asset library rather than generating new content. “I don’t want it to generate a random tree. I have a tree in my library. I know the tree that I’m talking about,” he explains. “And in theory, if you train a system to be aware of what your context is, you can say, ‘Put the tree there.’”

This measured approach also reflects Blender’s nonprofit structure and community-driven ethos. Unlike megacorporations that are rapidly restructuring around AI, the foundation must balance innovation with sustainability. “We are in a constant battle for making our project really, truly sustainable,” Siddie tells me. So even if they wanted to go crazy on AI, the development fund that supports core features cannot match the AI investments of companies orders of magnitude larger.

The result, however, is the same. The foundation’s strategy acknowledges AI’s potential while preserving what makes Blender unique: its commitment to empowering artists rather than automating them away. It makes sense, as this is the core philosophy that transformed an obscure open-source project into the creative industry’s most versatile tool.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0