A winding new bridge connects Honolulu’s downtown to the beach

Honolulu’s coastal Ala Moana Boulevard is a critical road in the Hawaiian capital, but it’s also a major hindrance. With six lanes of fast-moving traffic and few easily accessible crossing points, it’s effectively a hurdle between the city and its main public space, Ala Moana Park, and the broad beach there. Now, a stunning new pedestrian bridge has opened to make it easier to cross that rushing road.

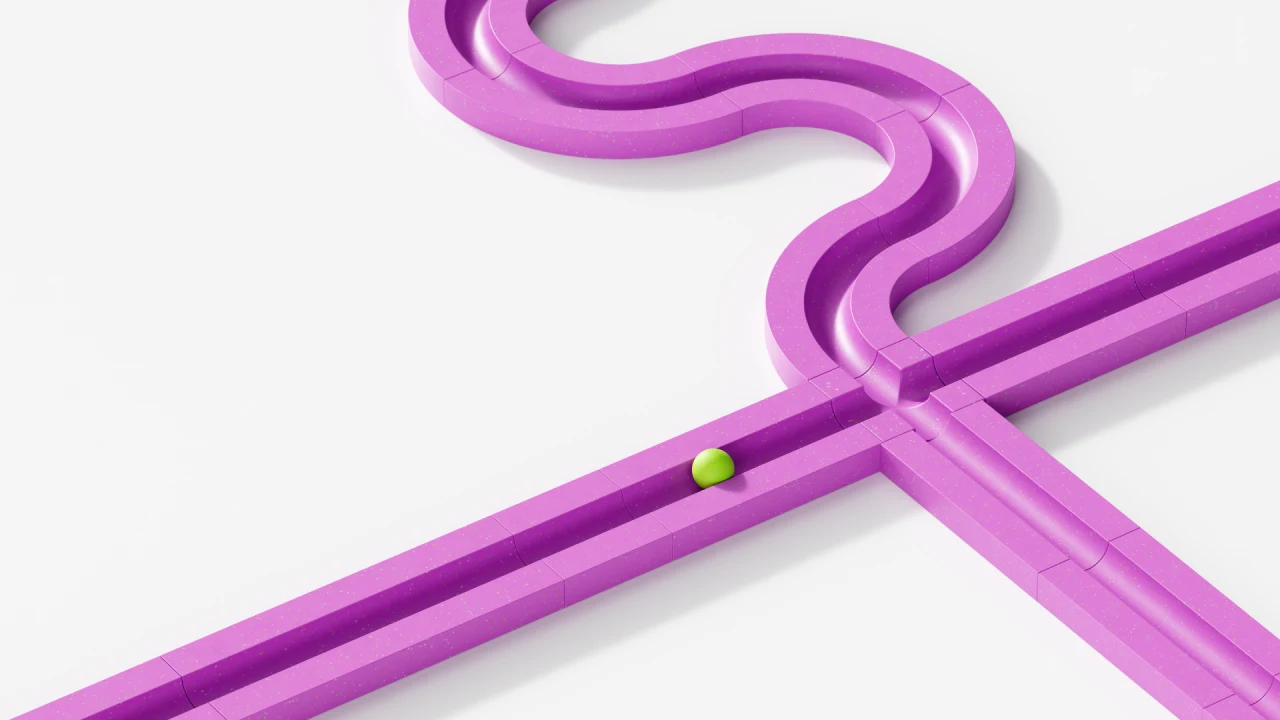

Winding its way from the edge of downtown Honolulu over the highway to a boat harbor and the corner of Ala Moana Park, the pedestrian bridge is an elegant piece of urban infrastructure, accented by artwork and connected to a series of paths cutting through a lush tropical landscape. It’s part of Victoria Ward Park, a two-phase publicly accessible open space connected to Ward Village, the 60-acre mixed use development that aims to redefine the urban realm in this part of the city.

Developed by Howard Hughes, Ward Village is a blank slate development on former warehouse land that will add, over the course of decades, more than 5,000 units of housing, nearly 1 million square feet of retail, and more than three acres of public greenspace. Several condo buildings are fully occupied and many future condos are already pre-sold, representing more than $6 billion in revenue, according to Howard Hughes’ 2024 annual report. Beyond its Honolulu project, the company made more than $1.75 billion in revenue in 2024, according to Pitchbook.

Building a bridge to downtown

Greenspace, primarily in the form of Victoria Ward Park, is a key part of the company’s strategy for luring residents and businesses, and turning Ward Village into a new model for urban development in Honolulu.

“A goal for Ward Village is to make the overall neighborhood significantly more walkable, comfortable, and safe,” says Doug Johnstone, president of the Hawaii region for Howard Hughes. Born and raised in Honolulu, Johnstone says that while the city is full of world-class amenities, its urban realm can sometimes be lacking. “It’s inherently a little disjointed and difficult to get around,” Johnstone says.

That’s why the Ward Village development—estimated to cost several billion dollars over a planned implementation period that runs through the 2030s—set aside the space for the park, and spent a considerable amount of time coordinating with state and local officials to get the pedestrian bridge built. Costing a total of $17.8 million, the bridge is technically a project of the state’s Department of Transportation. It was mostly funded by a federal grant, and Howard Hughes helped pay for the 20% portion of the budget required from local sources, donating land, funding the bridge design and providing environmental documentation.

“There’s a lot of folks wearing different hats that are trying to see it through, and making sure also it’s done well aesthetically and experience-wise,” Johnstone says. “It’s complementary to what we’re doing in Ward Village, but also something Honolulu can be proud of.”

Ocean-to-inland

Making the bridge possible is the existence of Victoria Ward Park, which was designed by Vita Planning and Landscape Architecture. The first phase of the park covers 1.4 acres from the edge of Ala Moana Boulevard inland, and is now open. The second phase, covering roughly 2 acres higher inland and more nestled in the Ward Village development, will finish construction later this year.

This ocean-to-inland connection became a guiding concept for the Honolulu park’s design, according to Don Vita, founder of Vita Planning and Landscape Architecture. “Going back and forth from the ocean up to the mountains is a very important cultural orientation in Hawaii and that’s exactly what we did with the configuration and the location of the park,” he says.

The section of the park closest to the ocean is more of a natural experience, inspired by the ecology of the region and the plants that were brought to Hawaii on canoes by its first settlers. Connecting to the pedestrian bridge, there are winding paths that slope up through this section of the park, passing by densely planted section and water features that reference the brackish ponds that would form on the shoreline. A large berm was created at the edge of the park as it approaches Ala Moana Boulevard, referencing the beach sand but also forming a buffer. “It encloses the space so that you could have this very calming respite from the active urban activities that Honolulu offers,” Vita says.

Higher up in the development and bisected by a road, the second section of the park will be more active, with space for vendors, events, and a playground. Having a street go through the space “at first was kind of a challenge,” Vita says. “We thought about it and it actually helped to tell the story of a passive and a more active space, and helped define those accordingly.”

Creating publicly accessible space has become a strategy for Howard Hughes, which has included more than 270 parks and recreation spaces within its community development projects across the U.S., including in Summerlin, Nevada, and in the Houston area.

In Honolulu, the new park space expands that ethos. But it’s still in a bit of a gray zone as a privately-owned space that is publicly accessible. Vita says that unique condition influenced the design of the park and he creation of what he calls visual permeability. “When people feel they’re in a place that others are looking at them, they tend to behave a little better,” he says. “Along with that visual permeability there’s actual physical permeability. We made the spaces very free flowing so it doesn’t feel you can’t come here.”

Making a new connection to the beach—and, conversely, reconnecting the beach to the city—is a way of giving downtown residents more access to the natural amenities of the area without expanding the city’s developmental footprint or sprawling beyond its edges.

“What we’ve been doing over the years is trying to really advance smart growth in Honolulu,” Johnstone says. “We want to really protect the environment and things that make it special and unique… The saying goes, if you want to keep the country country, you need to make the town town. And we’re doing a bit of that here.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0