The IRA was the biggest climate bill ever. It was also a marketing flop

When Dustin Mulvaney teaches a class in environmental law at a California university, he always asks a simple question: Who’s heard of the Inflation Reduction Act? Over the last three years, he says, only around 10 students out of hundreds have raised their hands.

His students aren’t alone. When the IRA passed in 2022, it was the largest climate investment in American history. But while climate nerds may know the law well, most people know little about what it includes. In one survey last year, only 10% of Americans who said climate change was a “very important” issue to them had heard much about what the Biden administration had done to try to tackle it. Another survey found that around a quarter of voters had never heard of the IRA at all.

“I consider myself to be a highly engaged voter,” says Britton Taylor, a brand strategist with more than two decades of experience working with big brands. “I take in tons of political media. And whatever Democrats did to message this or talk about climate, even I didn’t see it. Or if they did do stuff, nothing resonated with me.”

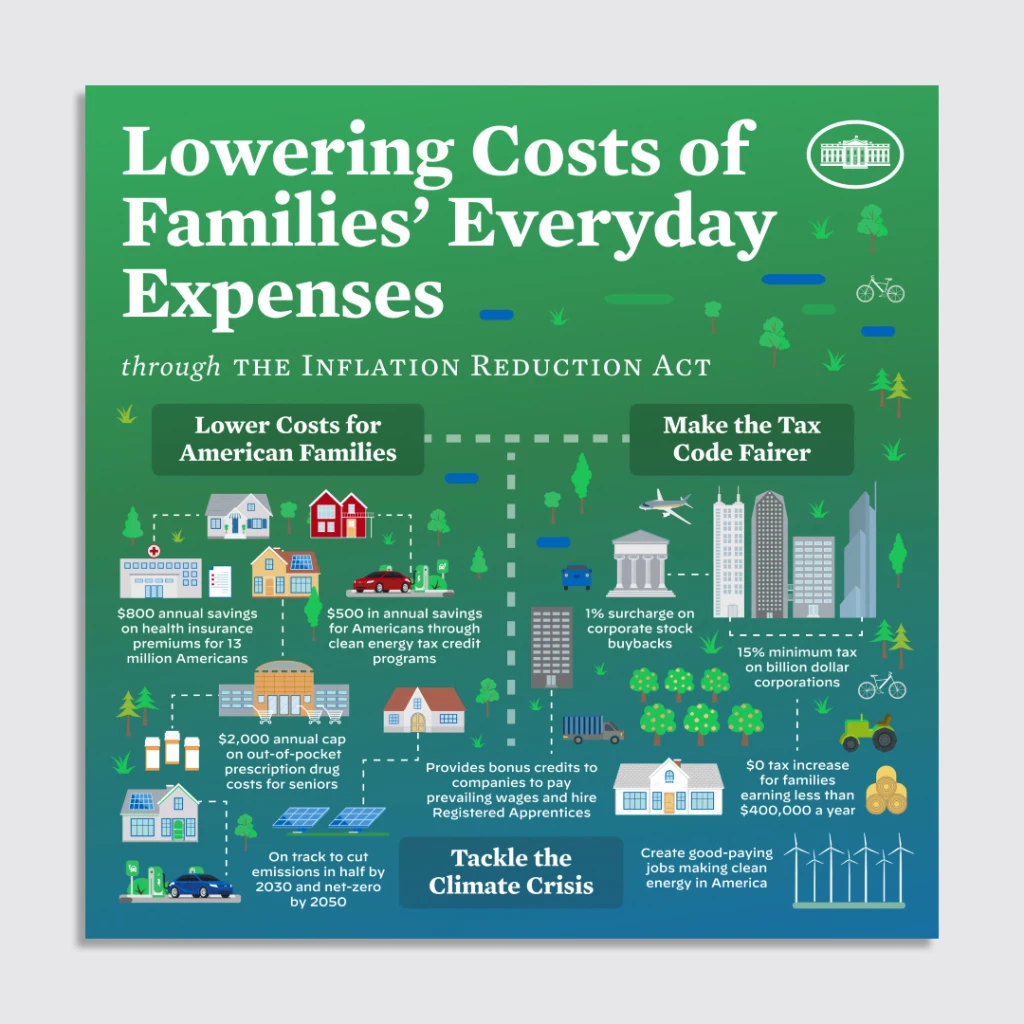

The law’s climate ideas are broadly popular—most people support extended tax credits for electric cars, incentives for American solar panel factories, and a slew of other programs designed to slash U.S. emissions 40% by 2030. Most Americans are also worried about climate change and how it’s affecting their lives, from extreme weather to home insurance rates. But the IRA was a marketing failure. Now it’s on the chopping block, as the Senate considers a bill that would eliminate or phase out almost all of it—despite the fact that it has benefitted red states and districts the most.

The problems started with the name

The bill was originally called “Build Back Better”—not a particularly creative name, since it had been used multiple times in the past after disasters like Hurricane Sandy. But it captured the basic idea: as the country recovered from the pandemic, the right policies could help the economy recover while also cutting pollution and improving workers’ rights.

Then came Joe Manchin, the West Virginia senator whose vote was necessary for the bill to pass. Manchin wanted a name focused on inflation. “The audience we were marketing to was a single man,” says Holly Burke, vice president of communications for the nonprofit Evergreen Action. The bill was renamed the Inflation Reduction Act.

Critics said the name was misleading. Manchin was right that voters cared about inflation, but the bill hadn’t been designed to directly address it. Models from the Congressional Budget Office and Penn Wharton projected that it would have little short-term impact on inflation. And while it would help reduce the price of energy and could help with inflation over time, the name didn’t really reflect what the bill was about.

It also set up the wrong conversation, some critics say. “The Inflation Reduction Act was, as a name, possibly one of the silliest self-owns I can recall,” says Anat Shenker-Osorio, a progressive strategist who does public opinion research and message testing. “It basically forced Democratic politicians to run around for an entire cycle saying ‘inflation, inflation, inflation.’ The point was inflation reduction. But people don’t listen to details, and you’re literally saying the word inflation over and over again, thereby reminding them of their pain point.”

Inflation did decrease, largely driven by other factors like Federal Reserve interest rate hikes, and the easing of pandemic-related supply chain disruption. But people couldn’t see those impacts in their own lives. “Americans struggle with math, and many of them don’t understand inflation to be a rate of change,” says Shenker-Osorio. “So when they’re told inflation is reduced and prices are not reduced, they say, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about. I go to the grocery store every week. There’s no inflation reduction.’ So, there’s a disconnect.”

Voters tend to trust Republicans more on economic issues, whether or not that’s justified. So Democrats may have been better served by framing the bill around something other than the economy, Shenker-Osorio says.

“If, for illustration, they had named this the ‘God Bless America’ bill or ‘We Love America Act,’ suddenly we’re having a conversation about what does it mean to love America, to do right by America? That allows you to talk about things like ensuring we have clean, renewable energy and that the places you loved to go with your grandparents as a kid will be the places you take your grandkids in the future. What you have to do is figure out, what is my brand advantage? What is the conversation where voters trust me most, regard me most highly?”

It also didn’t help that the acronym “IRA” already had multiple associations, including retirement accounts and the Irish Republican Army. “When the bill first passed, I Googled something about it, and all I got was information about the ‘Troubles’ in Ireland,” says Burke. “I was like, I could have seen that coming.” (And while laws often don’t have catchy names, “IRA” is particularly dull.)

Other laws have been rebranded after passing. The Affordable Care Act, for example, became widely known as Obamacare. (The name was initially used pejoratively, though the Obama administration eventually embraced it.) But no one attempted to find a different way to talk about the IRA.

The complexity didn’t help

The law, at 273 pages long, isn’t easy to concisely describe. There are at least 21 different tax provisions for clean energy alone, for example. It also goes beyond energy and climate to include things like lowering the cost of medicine.

Some of the programs also take time to roll out, making the direct benefits to voters harder to communicate. The tax credits for consumers were also somewhat hard to market—you probably don’t think about getting a discount on an efficient water heater until your current water heater breaks. And if you do eventually buy an appliance and get a tax credit, you might not realize where it came from. It also might not be obvious that a particular factory opened in your town because of the law.

“You have to connect a lot of dots to get from we passed this tax incentive, that had this additional bonus credit that incentivized companies to invest in your community, and create that job,” Burke says. “That’s a lot of leaps to make for an average voter who does not care about tax credits.”

There’s a lesson, she argues, for different policy design. “That’s not to say that we shouldn’t do abstract, wonky policies that make real impacts on people’s lives,” she says. “But if you want to have a politically durable victory, I think making sure that you’re incorporating things that are really understandable to the general public, and there’s a clear line from point A to point B: the government did this thing, and here’s how it supported my community.”

Some programs like this were in the original bill but eliminated, she says. For example, there was a clean energy performance standard that would have required utilities across the country to get to 80% clean energy by 2030. That’s “a more clear cut and intuitive way to understand how the Biden admin was delivering on climate than something with a fuzzier impact like ‘hundreds of billions in investments into clean energy,'” she says. “Both of those policies are good, to be clear, but saying we’re getting our entire grid to 80% clean electricity is a more immediately understandable impact.”

Boring stats don’t sell ideas

The Biden administration and supporters often focused on abstract statistics, like the fact that the IRA could create or support more than a million jobs nationwide. Those types of messages don’t really land. “The more conceptual and distant it is, the worse it does,” says John Marshall, a marketing executive who left the corporate world to launch Potential Energy Coalition, a nonprofit focused on climate. “The more local and human it is, the better it does.”

Creativity was also often missing in the messaging, which was typically driven by political consultants rather than creatives. “I thought about this a lot as someone who works in the more traditional advertising and branding world, as opposed to someone who’s anchored in the political space,” says Taylor, the brand strategist. “I feel like Democrats have fallen into a rut in terms of the way that they message . . . Like, ‘we have to explain stuff to people.’ It’s just boring and it does not resonate with people, especially young people.”

Being boring comes at a steep cost, as marketing studies have proven. “When you’re dull, it’s both ineffective and expensive,” Taylor says. “In the political context, being dull is extremely perilous for the Democrats, if you think about what’s at stake in terms of our democracy and our republic. You end up having to spend a lot more in media dollars in order to achieve the same amount of effectiveness than you would have with more compelling campaigns.”

There are exceptions. Potential Energy Coalition, for example, ran an ad for clean school buses that features a grimy bus driver handing out cigarettes to children—not boring. But Taylor argues that the Democratic Party would do better if it worked with a wide swath of experienced marketers.

“There’s been this firewall between the creative community and the political community,” he says. “I really wish that firewall would come down, because I think there’s so many people in the world of advertising that would love to help. Every brief that I get from brands now is, how do you make a dent in culture? Or how do you get talked about? It’s all about generating fame for your brand like press, earned media. That’s what we’re good at, or at least the really talented people in advertising. And I wish more of those people could get back in the political world.”

Climate wasn’t the focus

Most messaging about the IRA focused on economic benefits, rather than climate. The economic benefits are significant, to be clear. The tax credits for consumers, for example, help pay for appliances that can slash energy bills. “I think part of the conversation that we collectively should be having right now is, what are the best ways to reduce energy costs for American families?” says Ari Matusiak, co-founder and CEO of the nonprofit Rewiring America. “An obvious way to do that is by people having more efficient machines in their homes that use less energy and deliver better performance. And that’s exactly what these tax credits are helping to pay for.”

Surveys showed that Americans were worried about daily costs. That’s obviously a very real concern. Still, that doesn’t mean that the dominant messaging should have necessarily been about inflation or the high cost of living, says Shenker-Osorio. “You have to decide what the conversation is going to be about,” she says.

Climate change ranks lower when people are forced to compare it with the economy. Still, Americans do care about climate impacts, and they respond to strong messages about it. “We’ve done hundreds and hundreds of tests on this,” says Marshall from Potential Energy Coalition. “There is a latent, easily [activated] concern in the minds of almost all citizens that something is wrong with the planet and that we should be addressing it. That is a concern that touches people of all political persuasions. And so when you message the fact that we need to stop that from happening, it is very motivating.”

The dire threat to the planet is really the main reason for people to support clean energy. “It’s a pretty major reason—it’s actually bigger than the other things,” Marshall says. “And so we are chickening out of our big ‘why.'”

As Potential Energy Coalition tests different messages, the most effective are about the direct consequences of climate change on people’s lives. “The messaging needs to move from morality to materiality,” he says. “It shouldn’t be something one does because of my particular values. It should be something that one gets behind because it materially affects their lives . . . how it’s affecting your life, your kids, your farm, your insurance costs.” In the group’s testing, the least effective messages were promises of economic benefit.

How much does marketing matter for policy?

Even if most Americans don’t know the details of what’s in the IRA, the incentives have been popular. “We’ve seen massive uptake of the various programs,” says Matusiak. Taxpayers claimed more than $8 billion in credits on their 2023 returns—more than twice what the government had projected. Millions of people have used a tool that Rewiring America created to help households calculate how much they could save through tax credits and rebates. Companies invested hundreds of billions in new factories to make electric cars, solar panels, and other clean energy tech (though billions in planned investments have now been cancelled since Trump changed the direction of federal policy). The majority of the investment in clean manufacturing went to red states, despite the fact that no Republican voted for the legislation.

If the IRA’s initiatives had stayed in place as long as they were intended to—10 years—it wouldn’t matter so much whether most people knew that they existed. If you found out about a tax credit through a contractor, or TurboTax, and didn’t know where it originated, you’d still be able to use it. But if voters still aren’t making the connection between the programs and how they benefit their own lives, they probably won’t feel motivated to advocate for them now that they’re under threat. And name recognition isn’t enough on its own—even Medicare is at risk in the current version of the budget bill. But arguably, better marketing could have helped.

The biggest hurdle in marketing something like the IRA or another climate policy isn’t the exact message, Marshall says. Even though some messages perform better than others, climate messaging in general resonates. But it’s harder to make sure that those messages are actually reaching voters. “The major challenge on climate legislation is a distribution challenge rather than a messaging challenge,” he says. “We don’t have nearly enough spokespeople, we don’t have nearly enough faces of the movement. We need a lot more people talking about it.”

Political will for climate action could easily grow. “We, the citizens, haven’t changed,” he says. “The government changed . . . but the regular people haven’t changed. They’re getting the same limited amount of information. They still care a lot about this issue, and they’re phenomenally moveable on the issue.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0