Why do we trust certain people (even when we shouldn’t)?

Why are some people perceived as more trustworthy than others?

In a perfect world, the answer would be simple: because they are more trustworthy. In other words, ideally, the average human would be perfectly able to infer someone’s trustworthiness by objectively assessing their degree of honesty, reliability, and integrity.

But, in the real world, things could not be more different.

Indeed, there are many factors unrelated to a person’s actual honesty that determine whether that person is generally seen as trustworthy or not. Here is just a small selection of them:

1. Attractiveness: The halo that blinds

We don’t just trust attractive people more. We also assume they are smarter, kinder, more capable, and even morally superior. This is the classic “halo effect,” the well-documented cognitive bias in which our overall impression of a person (often based on a single positive trait like physical attractiveness, confidence, or status) influences how we judge their unrelated traits, such as intelligence, morality, or trustworthiness. In other words, if someone looks good or sounds smart, we are more likely to assume they are good and smart.

The term was first coined by psychologist Edward Thorndike, one of the fathers of social psychology, in 1920, when he observed that military commanders who rated their subordinates as physically impressive also tended to rate them higher on leadership, intelligence, and character, even when there was no evidence to support those links. This spillover effect distorts objective evaluation, making it harder to see people clearly.

In practical terms, the halo effect explains why charismatic leaders get away with bad behavior, why attractive people are presumed innocent, and why we often misplace trust in those who simply seem impressive. This is perhaps the most durable illusion in human social perception.

The definitive quantitative review comes from J.H. Langlois, who conducted a meta-analysis of 76 studies to test whether “what is beautiful is good” holds up across various domains. It does. Attractive people were consistently rated more positively across virtually all traits, including honesty and trustworthiness, by both adults and children (yes, even 5-year-olds assume people are more trustworthy when they meet predefined societal archetypes of beauty or attractiveness). The researchers concluded that “attractive individuals are judged more favorably than unattractive ones, even when there is no objective basis for such judgments.”

This bias is not just persistent; it is also consequential. In legal settings, for instance, attractive defendants receive lighter sentences than unattractive ones for identical crimes. In hiring, attractive applicants are rated as more qualified regardless of their résumé. And in leadership, beauty can serve as a false credential for competence.

If beauty is a signal, it’s a deceptive one. Especially because attractive individuals learn (early and consistently) that charm and appearance open doors. Over time, this can create a mismatch between how trustworthy they appear and how trustworthy they are. And this mismatch is something many learn to exploit. In theory, it should lead to a self-correction over time, such that beauty or appearance ceases to act as a signal of trustworthiness (becoming instead a fake signal or noise). So far, though, it is clear that even if you can’t judge a book by its cover, people still do; and there is no second chance for a good first impression.

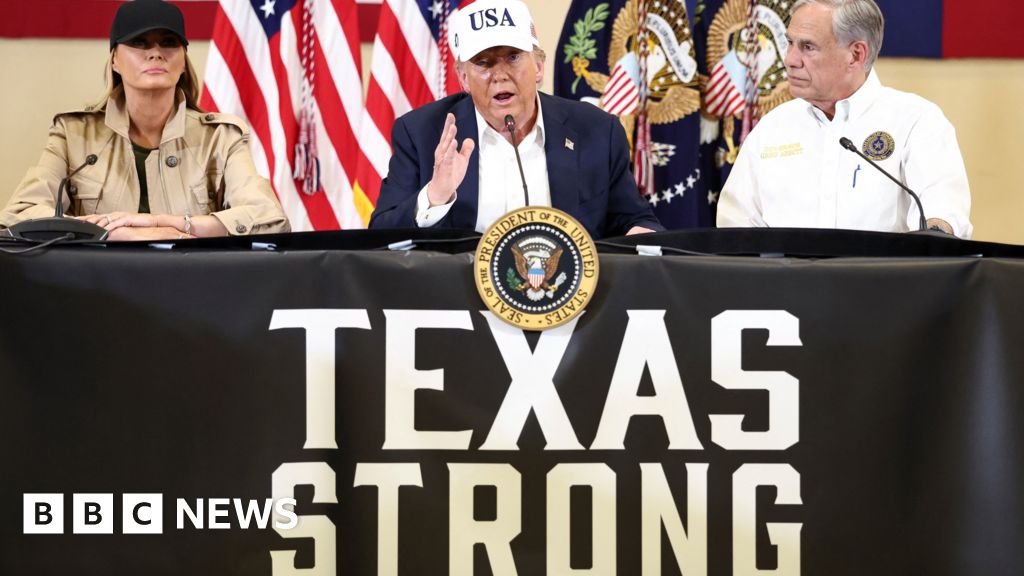

2. Social class: The wealthier they seem, the more we trust them

Status symbols trigger unconscious biases. A seminal study found that people wearing luxury brand logos (think Ralph Lauren, Rolex, or even carrying a Starbucks cup) were judged as more competent and trustworthy, regardless of their actual behavior. Note that there are only trivial differences in actual prosocial behavior in general by social class or socioeconomic status, so the perceived effect is more like a self-fulfilling prophecy and subjective or cultural projection, than a reality-based inference.

In fact, some studies suggest that certain antisocial behaviors are more frequent or likely in higher status individuals. In a large-scale study, higher socioeconomic status was associated with significantly higher rates of unethical behaviors in a range of contexts, from cheating in games to endorsing dishonest behavior in hypothetical scenarios. The researchers also found a negative association between social class and empathy. In other words, people with more resources and power were less likely to consider the perspectives of others or feel compelled to behave ethically.

So, while our instincts might nudge us to defer to the affluent, the evidence says we should do the opposite: interrogate the credentials behind the confidence, and ask whether their influence reflects substance or merely style.

3. Charisma: A red flag in disguise?

Charisma is often mistaken for authenticity, but as any psychologist will tell you, it’s frequently a performance—and one that masks darker traits. Narcissists and psychopaths tend to score high on perceived charisma. They know how to manipulate impression management to engineer trust. In fact, according to a meta-analysis, individuals with high narcissistic traits are more likely to rise to leadership positions, in part because their confidence and charm seduce people into trusting them, even when that trust is undeserved. Put simply, we confuse style for substance. And we pay for it later.

4. Familiarity and fluency: Trusting what feels easy

This is perhaps the most pervasive finding of all. We tend to trust people who look like us, speak like us, or fit our mental models. This is called the mere exposure effect, and it means we trust what we recognize, even when it’s not trustworthy. For example, research has shown that people with easily pronounceable names are seen as more likable and even more trustworthy. In the corporate world, people with “simpler” or Anglo-sounding names are more likely to be hired and promoted. It’s bias masquerading as gut instinct.

This bias toward the familiar is not just an aesthetic preference, it can be morally distorting. Psychologist Paul Bloom, in his book Against Empathy, argues that our instinctive emotional empathy is narrow, biased, and often unethical precisely because it is selective. We are more likely to feel empathy for those who resemble us, think like us, or share our background, even when that empathy is misplaced. Bloom contends that this favoritism can lead to harmful decisions, such as favoring charismatic insiders over competent outsiders or excusing unethical behavior from those we identify with. In other words, when familiarity governs our moral instincts, trust becomes parochial, and our judgments lose objectivity.

So how can we get better at trusting the right people — especially in a world where style so often disguises substance?

1. Focus on behavioral consistency, not first impressions

Instead of asking “Do I like this person?” or “Do they seem confident?” ask: “Have they behaved predictably and reliably over time?” Research in personality psychology shows that trustworthiness is strongly correlated with the trait of conscientiousness, which manifests as consistency in behavior, follow-through, and self-control. Interestingly, conscientious people may often be the exact opposite of entertaining, charismatic, attention-seeking, narcissistic individuals. At times, they can be quite boring in the sense of being structured, organized, methodical, and predictable, which is precisely what makes them so reliable and trustworthy. You probably won’t have much fun if they organize your vacation (a spreadsheet for everything and zero time for serendipity), but they are your perfect choice if you want someone to organize or manage your finances.

2. Discount overconfidence—it is often a proxy for deception

People tend to mistake confidence for competence, and even more dangerously, for integrity. But the research is clear: overconfidence is often unrelated to actual ability, and it is positively correlated with deceit. A widely cited study showed that individuals who were most overconfident in their self-assessments were also most likely to cheat or deceive others when given the opportunity. In other words, if someone always seems certain and never admits what they don’t know, that is not a sign of strength. It is a sign of strategic self-presentation.

3. Judge character through adversity, not performance in ideal conditions

People’s true nature is more visible when things go wrong. Research on moral character and trust by Nancy Darling and colleagues shows that stressful or ambiguous situations expose discrepancies between stated values and actual behaviors. If someone remains generous, fair, or honest when there is no benefit to doing so, or when the pressure is on, it is a much stronger signal of trustworthiness than how they act during polished moments or well-rehearsed pitches.

4. Take your biases seriously, not personally

Everyone is biased. But most people assume that they are the exception. In one famous study on bias blind spots, over 85% of participants believed they were less biased than the average person. That illusion of objectivity is precisely what makes us so susceptible to misplaced trust. You are not a human lie detector. None of us are. But you can become more accurate if you start by doubting your own instincts and controlling for the predictable ways they go wrong.

Trust, then, is not just a matter of judgment. It is a mirror reflecting our hopes, biases, and blind spots. We trust not because others are trustworthy, but because we need to believe they are. And the more persuasive the illusion, be it beauty, confidence, wealth, or likability, the more likely we are to mistake it for the real thing. This is not a flaw in individual reasoning, but a feature of human cognition. Our brains are designed to take shortcuts, especially when it comes to social decisions. The problem is that those shortcuts were optimized for tribal life, not complex modern systems where bad actors can scale their charm and weaponize it.

The solution is not to stop trusting. It is to trust smarter. That means getting more curious about people’s track records than their charisma, more attuned to patterns than first impressions, and more willing to scrutinize those who seem above scrutiny. It means accepting that your instincts might be less accurate than you think, especially when they feel most certain. Ultimately, the goal is not to become cynical, but discerning; to replace reflex with reflection, and wishful thinking with evidence.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0