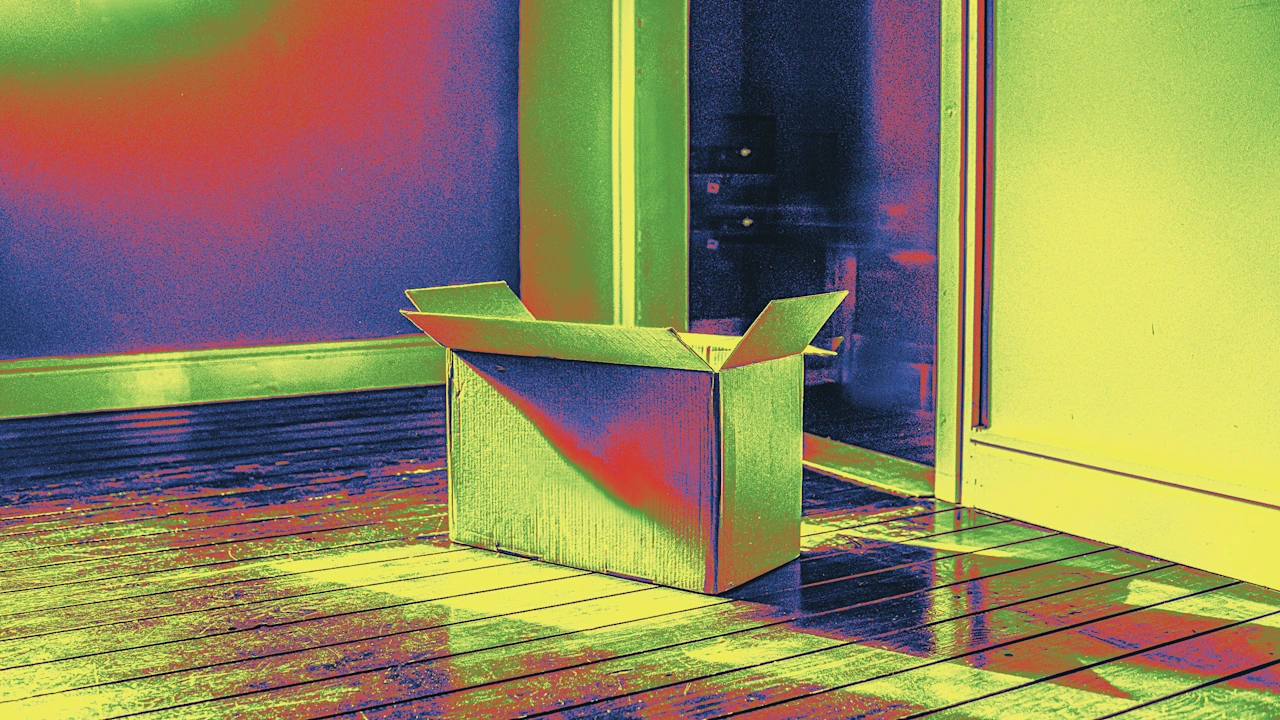

How ‘good cause’ eviction laws aim to protect renters from eviction

Matt Losak got interested in evictions when he was nearly subject to one. He was working for a union, which required frequent travel. One month he accidentally left his rent check on his refrigerator and left. He called the property manager, who told him it wouldn’t be a problem as long as he gave her the check when he returned and paid a $25 late fee, all of which he did.

Six weeks later, he received an eviction notice for failure to pay rent.

Losak fought the eviction off by proving that the property owners had signed the eviction papers after having already cashed his check. “I caught them by the toe,” he said. But the experience focused him on the fact that, in most places, landlords can move to evict tenants for any reason. It’s one part of why evictions have been climbing steadily since the pandemic, even outpacing pre-pandemic levels in some places.

Losak helped found Renters United Maryland in 2017, and enshrining “good cause” protection from eviction was his number-one issue. Good cause laws require landlords to have a specific reason for evicting someone or terminating their lease, although typically tenants can still be removed for things like violating lease agreements or failing to pay rent. The lack of good cause protections, is “a major loophole,” he says, allowing a landlord to, “based on whim and caprice, rip somebody out of their home.”

When Losak first started advocating for good cause, he says state lawmakers “literally laughed in my face.” They didn’t buy that it was a big problem, not to mention that landlords and their lobbyists, who oppose such laws, hold huge sway.

But his organization has worked to build support over the years. It pushed the idea that a lack of stable housing leads to concrete costs in mental and physical health declines, lower academic achievement for children, and higher crime rates. “There’s all types of costs, financial and social, that people are beginning to recognize are directly related to unstable or poor quality homes,” he says.

The Pandemic Effect

Then came the pandemic, which “clearly was an accelerant” and focused state lawmakers’ attention on housing policy, he says. In 2020, experts and analysts put the number of potential evictions at anywhere between 17 million and 28 million. “That fear of widespread evictions led courts and others to look at the eviction process differently and try things out,” says Sarah Gallagher, vice president of state and local innovation at the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Eventually eviction moratoria and rental assistance would help to keep the number of evictions low. Now, however, those protections are gone and rents are rising rapidly. The housing crisis, Gallagher says, is “even worse than it was before the pandemic.” Rents rose 29% between 2019 and 2023 and homelessness is at a record high.

So lawmakers have been looking for other tools to continue helping people stay housed. Maryland was among a number of other states that considered good cause eviction protections during this year’s legislative session. After a “bottleneck” against advancing legislation was ousted, the bill came close to passage. Losak was able to marshal support from a wide coalition that included the ACLU, NAACP, unions, and even the governor. Legislation passed the state house, only to die in the senate under pressure from landlord lobbies.

Losak noted that next year is an election year for the Maryland legislature. “There is a bubble of anger and frustration that is growing among a huge number of Marylanders that might very well have a political impact,” he says. “We’re optimistic.”

Fights are now brewing in Chicago and Rhode Island. These cities and states are looking to join a growing movement: 11 states and 27 localities have now passed good cause laws. The majority of those laws were passed in the years since 2020. “It is gaining momentum,” Gallagher says.

Reducing eviction rates

Research has found that these laws reduce eviction filing rates, keeping people both housed and firmly rooted in their communities. Academics have also found that good cause protections in California, Oregon, and New Hampshire didn’t decrease housing production after they passed.

New York State passed good cause eviction protection last year that went into effect immediately in New York City and allowed other places to opt in. It used to be that, as long as a New York landlord filled out all the forms correctly, it could evict someone. But now landlords can’t just say, “Well, I want this person out,” says Judith Goldiner, attorney in charge of the civil law reform unit at The Legal Aid Society.

Under the new law, landlords have to offer their tenants a lease renewal unless they can prove they have a good reason not to, such as illegal behavior or the need to demolish a building. It also capped rent increases. But the law came with a long list of exceptions, including any building built after 2009, luxury buildings, and buildings owned by someone with a portfolio of 10 or fewer units. The carveouts mean that, while “it’s a useful tool,” Goldiner says, it is often “unduly complicated and hard to explain.” It can be hard even to figure out what entity owns buildings, let alone how many others they own.

The law is still new, so there haven’t been decisions hammering out exactly what counts as a good cause for evicting someone. Still, Goldiner knows of a number of tenants who were able to use it to negotiate leases instead of ending up in eviction proceedings. “Definitely it’s been really helpful for a lot of people to actually avoid litigation,” she says.

Expanding tenant protections

Good cause laws won’t stop evictions all on their own. “There isn’t one protection that’s going to do it all,” Gallagher says. “You have to look at putting in tenant protections at all stages of the housing and eviction process.” That includes starting with regulating how tenants are screened by landlords so they aren’t discriminated against all the way to sealing eviction records after tenants are forced out so they aren’t penalized when trying to get housing in the future.

Still, good cause laws are particularly important because they help insulate tenants from retaliation for asserting any rights they do have. They enable tenants to speak out against unsafe or unhealthy housing conditions or other abuses. Under good cause laws, landlords can’t kick people out just because they, say, asked for repairs. And policies like right to counsel, which guarantees legal representation in eviction proceedings, are only useful if there are actual rights for lawyers to defend.

If tenants “don’t have the ability to advocate for their rights, then what good is the protection?” Gallagher says.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0