The Wrigley Building: the making of an icon

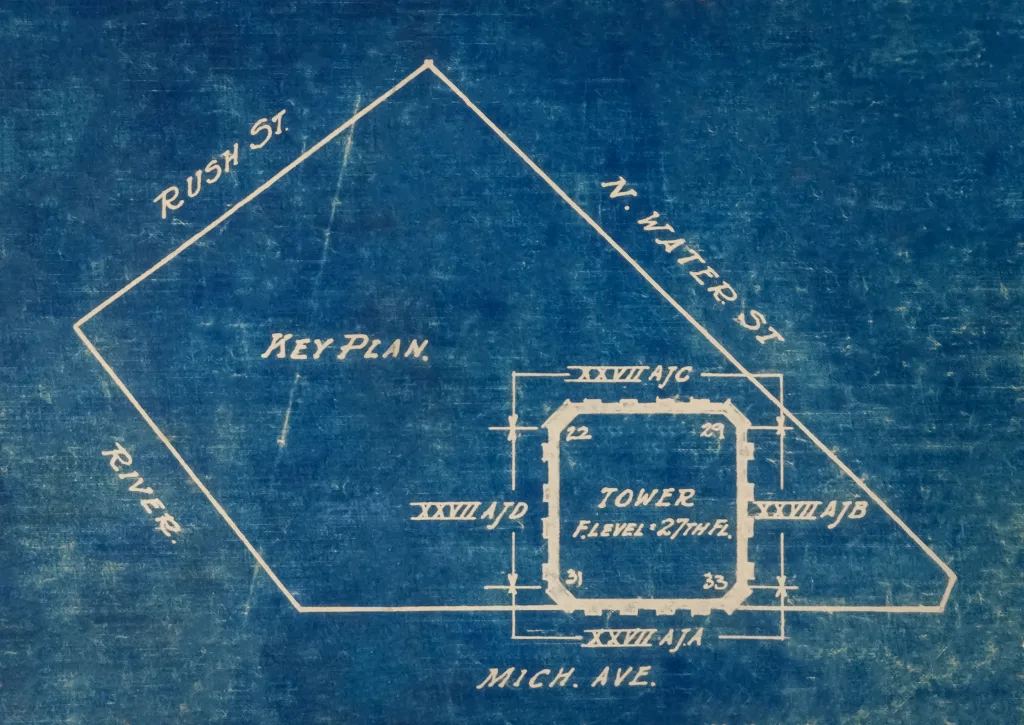

Charles Beersman was thirty-one when he began designing the Wrigley Building, young even in those days for such a major commission. Why he was given this break is unknown. From the very beginning, however, it is clear that he developed close bonds with Peirce Anderson and William Wrigley. He likely started with a sketch, as he was taught by Paul Cret all those years ago at the University of Pennsylvania—a quick drawing of the facade and footprint and probably a detail of the clock tower.

But before that, he would have walked the site and reviewed all the data relating to dimensions and square footage. More importantly, he would have met with William Wrigley, probably more than once, and questioned him about his plans for the building and what he hoped it would convey in terms of the company and its product. Years later, Beersman would tell his daughter that Wrigley was his favorite client.

It is easy to see why. Wrigley’s approach to architecture was in many ways identical to his approach to marketing. Be anything but ordinary! Stand out, make people notice you, give them something that feels like a gift. And don’t take yourself too seriously. For Beersman, it was an open-ended invitation to dig deep into his imagination and create something extraordinary.

Chicago debut

Beersman would also have been aware that the building would be his debut in Chicago and would determine how he was regarded for the remainder of his career. Ironically, the architect would never again have the freedom he enjoyed with this project. The building was and is unique, the product of a certain moment and of personalities who came together to create a lasting work of art. It also marked the last time Beersman would channel his mentor, Julia Morgan, in so forthright a manner. (In some ways the Wrigley Building is Morgan’s Los Angeles Examiner Building lobby turned inside out.)

The uniqueness started with a site that was both advantageous and problematic. Advantageous because of its visibility. Fronting on the river and a vast new plaza, whatever was built there would dominate the Near North landscape for miles. Problematic because of its shape and dimensions. A true Beaux-Arts building is by nature completely symmetrical. The Wrigley Building, however, is completely asymmetrical—“cockeyed all the way around,” as William’s son, Philip, later characterized it.

There was also the added challenge of the Wrigley being a four-sided building. Most buildings are four-sided, of course, but most are also designed to fit into a block or a corner where two or more of those sides will never be seen. When a building sits by itself, it is held to a higher standard. It becomes an object and a form of public sculpture. (Which, of course, is precisely what Wrigley wanted — offices, yes, but also a building that would be the architectural equivalent of his illuminated sign in Times Square.)

“Frozen music”

In 1919, the height limit for buildings in Chicago was 260 feet, with a proviso that allowed towers and other ornamental features to rise to 400 feet. The building Beersman designed was 210 feet. It had eighteen stories, two of which were below street level. The eleven-story tower soared to 398 feet.

If architecture is, as Goethe famously called it, “frozen music,” the Wrigley is a symphony—a series of movements and crescendos culminating in an explosion of ornamentation at the apex of its clock tower. The tower is at the heart of the building’s undeniable grandeur.

The facade of the Wrigley is divided into what was then the typical Beaux-Arts arrangement of base, shaft, and capital or cornice. There are ornamental stringcourses at the third, fourth, fourteenth, and fifteenth levels, and the four- teenth level includes a flock of terra-cotta eagles with wings spread wide that gently lift the upper floors. At the top is an exquisite grouping of unoccupied spires and setbacks that serve as a transition to the eleven-story tower.

A magnificent four-sided clock with faces 20 feet in diameter occupies the eighth and ninth floors. The clock hands were made of pine soaked in oil and painted black. The hour hands are 7 feet long, and the minute hands are 11 feet long.

The floor above the clock was officially unoccupied but was designated for use as an observation deck. Above that is a circular Greek temple, which in turn is topped by a lantern and a crocketed spire. The lantern originally contained a flashing red and white beacon that was visible for twenty miles. Upon completion the Wrigley was the tallest building in the city, although it would hold the title only briefly.

Structurally, the Wrigley is a typical steel-frame Chicago high-rise of its period, with fifty caissons encased in concrete going down 100 feet to bedrock. But almost everything else about it derives not from Chicago—a city Beersman had never visited—but from the metropolises Beersman knew best: San Francisco and New York.

A mash-up of masterpieces

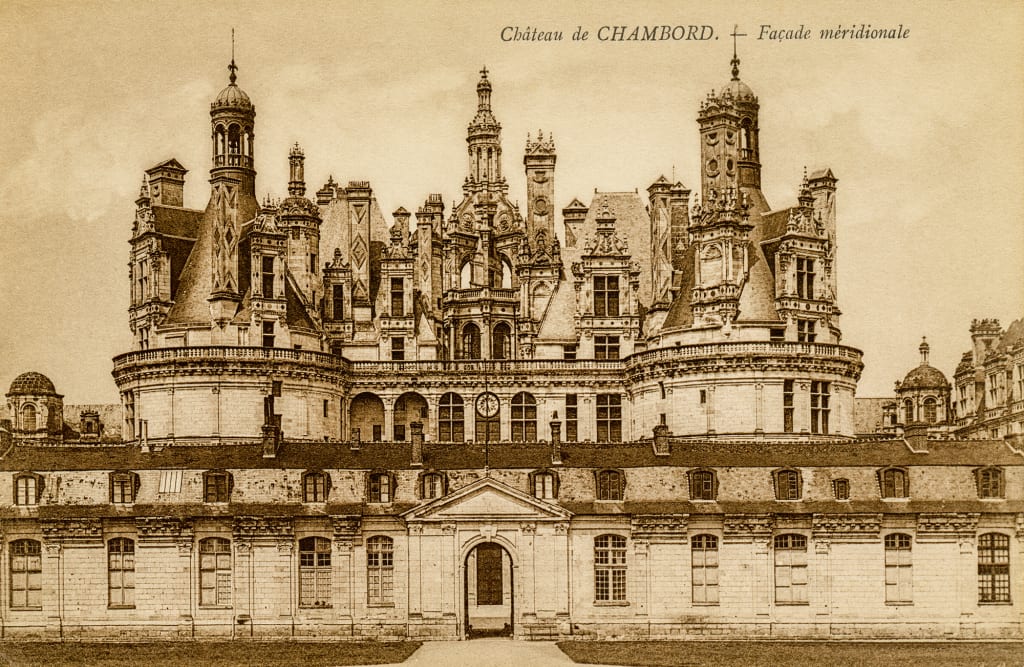

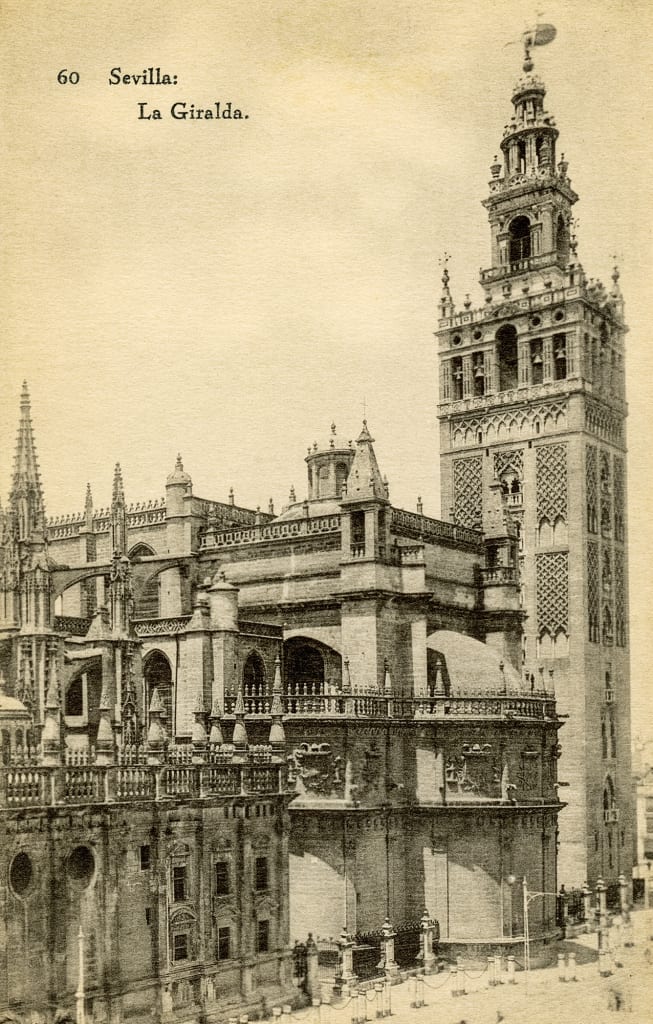

The completed building is basically a mash-up of two Renaissance masterpieces—the Château de Chambord in France’s Loire Valley and the Giralda Tower in Seville, Spain—with additional inspiration provided by McKim, Mead & White’s Municipal Building in lower Manhattan. Whether Beersman saw either of the first two on his 1914 sketching tour is unknown, but he would definitely have been familiar with the third, as he was living and working in New York when it was completed.

The Château de Chambord is an immense 440-room castle built as a hunting lodge for King Francis I over a twenty-eight-year period starting in 1519. No definite architectural attribution has been found, but it is likely that Leonardo da Vinci played some role in the design. The artist and inventor lived not far from the site, and several of Chambord’s most notable features—including an ingenious double staircase and a surprisingly modern latrine system—are described in da Vinci’s famous notebooks.

The château is also renowned for its skyline—a dazzling collection of highly ornamented turrets and towers executed in glistening white limestone that novelist Henry James described as “an exaggeration of an exaggeration.”

And then there are the salamanders. Francis I took as his emblem the mythological salamander, a creature that supposedly could live in fire. Architectural historians have counted more than three hundred depictions of salamanders—many wearing crowns—throughout Chambord. Beersman would re-create many of these features—including the salamanders—at the Wrigley Building.

The Giralda Tower began as a minaret for a mosque in 1198 but did not achieve its final form until it was renovated into a bell tower in 1528, long after the mosque had been converted into a Christian cathedral.

The heavily ornamented square tower is constructed of brick and marble and is 323 feet tall. At the top is a 19-foot metal sculpture of a woman—La Giralda—that doubles as a weathervane. (The word giralda is Spanish for “she who turns.”)

A collection of spare parts?

Does this mean that the Wrigley Building is nothing but a collection of spare parts? Not at all. Château de Chambord, the Giralda Tower, and the Municipal Building represent ideas and archetypes that are endlessly mutable and adaptable. Beersman’s genius—and the ultimate greatness of the Wrigley Building—relates to the uses he makes of these venerable models.

For example, the original Giralda Tower has the weight and ruggedness one associates with load-bearing structures. Beersman’s interpretation, however, which includes steel construction, has the lightness and opalescent beauty of a pearl necklace.

Due to the Wrigley’s irregular dimensions, it functions almost as a prism, with different views from different directions. The view from the south is romantic. One journalist wrote, “At a distance of about a mile, one becomes suddenly conscious of the new presence . . . one can see the tower in all the airy grace of its many pinnacles and turrets much as one might glimpse the towers of some distant castle set on a rock.” The east facade, meanwhile, provides the illusion of symmetry and has a compressed verticality that—combined with the explosive energy of the clock tower—creates a thrilling sensation of upward thrust.

And then there’s the north facade, which is startling—“a huge, sharp dominating prow, for the Wrigley building is only five feet wide at that point,” wrote one journalist. “It seems to cut the air and to be slowly bearing down on the spectator with an awful majesty quite overpowering.” It clearly references D. H. Burnham & Company’s Flatiron Building in New York, another structure that makes a virtue of its irregular site.

Radiating joy

In a city of mainly dark brown and dull gray buildings, the Wrigley stands out for its bold coloration. The facade is enameled terra-cotta in six different shades of white, starting with snowy white at the base and gradually acquiring a yellowish tint as it rises. The effect, according to one observer, is “as if the sun were always shining on its upper reaches.” (In order to maintain this illusion in Chicago’s then-sooty atmosphere, the china-like facade needed to be washed four times a year in the early twentieth century.)

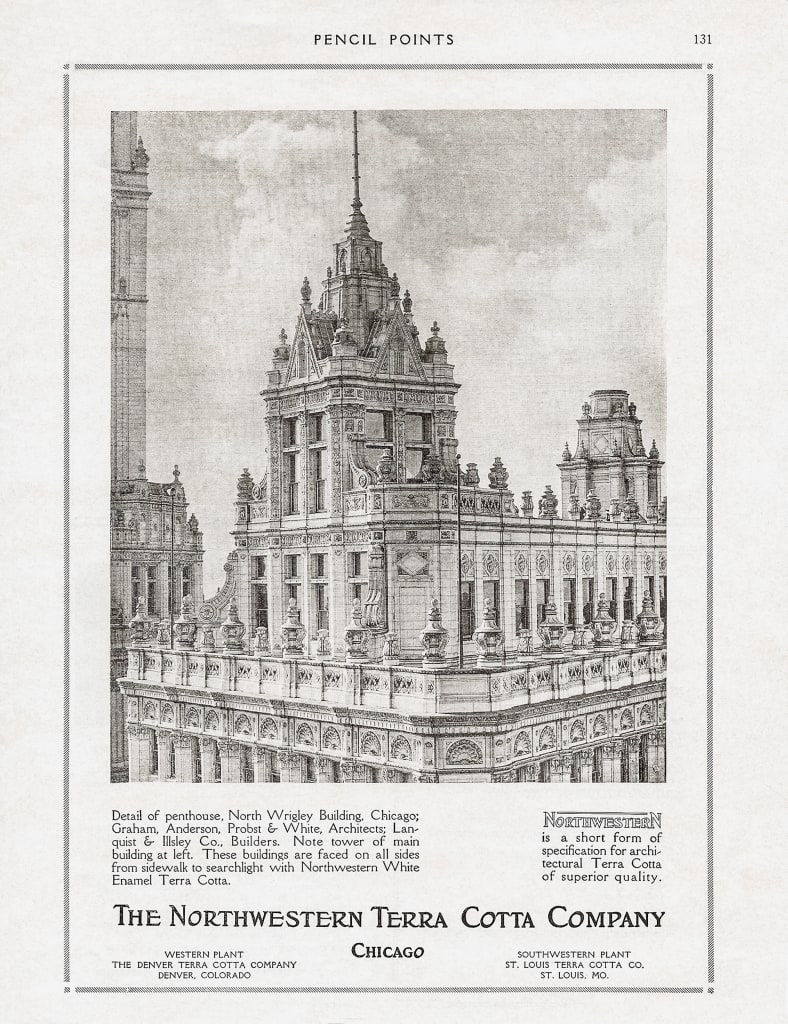

The facade was fabricated by the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company, a Chicago-based firm with a long history of working both with Burnham and with Graham, Anderson, Probst & White on such monumental projects as the Rookery Building (1888), the Reliance Building (1894), the Fisher Building (1895), the Railway Exchange Building (1903), the Conway Building (1912), and the Continental and Commercial National Bank (1912).

The Northwestern Terra Cotta Company operated out of a multi-acre complex at the corner of Clybourn and Wrightwood Avenues on the city’s north side. With more than 1,500 employees, it was the largest terra-cotta firm in the country. The president was Gustav Hottinger, a Viennese immigrant who was one of the original founders of the firm in 1887. The company’s reputation was such that “Northwestern or better” was a standard phrase inserted into contracts by architects in order to denote quality levels.

As the firm that fabricated much of the terra-cotta for the architect Louis Sullivan’s extravagantly ornamented buildings, Northwestern was used to impossible demands. But even for Northwestern, the Wrigley’s incredibly dense and compacted ornamentation was a challenge.

It is an astounding menagerie Beersman has assembled here. In addition to the omnipresent salamanders, there are lions, horses, rams, eagles, raptors, crocodiles, roosters, swans, and dolphins as well as a plethora of mythological griffins, dragons, and gargoyles. Also present are cherubs and winged putti, dancing youths, grimacing satyrs, and what look to be carnival masks. All of this is in addition to twisted columns, niches, flaming braziers, stacked vases, rosettes, balustrades, molten finials, and seashell and poppy-flower cornices that embellish every available surface. The building has extraordinary animation. It radiates joy.

Night lights

The wildlife is depicted both in motion and at rest and with close attention to detail. Taken together, the grouping suggests that Beersman had been storing up imagery for years and was determined to use every last bit of it on this one project. Architectural ornamentation is usually limited to walls and surfaces that can be seen from the street. The Wrigley, however, has great swathes of ornamentation on the roof and tower that are all but unviewable. The ornamentation is there, presumably, to provide authenticity. As at the Château de Chambord, its implicit model, the ornamentation is part of the architecture, not an expendable add-on. (The architects of the Renaissance believed such unviewable ornamentation was meant not for humankind but for God.)

The final touch was the exterior lighting, and here Beersman’s early training in electrical engineering proved critical. No one knows who suggested that the building be lit at night. But the obvious inspiration was Times Square, an area famous for its nighttime effulgence. Both Beersman and Wrigley had connections to Times Square—Beersman’s apartment at Westover Court was just off the square, while Wrigley had been a prominent advertiser there for many years.

The system Beersman installed consisted of 198 projectors with 500-watt lamps and 16 projectors with 250-watt lamps. The total power consumption was 103,000 watts, while the cumulative candle power was more than 25 million. The system added 30,000 dollars (about 437,000 dollars today) to the budget, and it was estimated that the annual cost of operating it would come in at just under 30,000 dollars. An architecture magazine of the period commented, “Although [the building’s] appearance at any time is impressive, it is particularly so at night when fully illuminated by a system which is itself unique and which is said to be the most complete illumination of a single building in the world. . . . Certainly it is for the Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co. the most striking possible form of advertising, indelibly impressing upon the minds of tens of thousands of people daily the Wrigley Chewing Gum product.”

Functional and businesslike

The final cost of the building was 3.79 million dollars (about 60 million dollars today), almost double the initial estimate from late 1919. At $1.22 per square foot, it was one of the more expensive office buildings of its time. Money did not appear to be a problem, however. The building carried no mortgage. Wrigley paid for it out of company reserves.

The higher-than-average cost must have related to the wildly embellished exterior. It certainly wasn’t due to the interior. One of William Wrigley’s inflexible rules of marketing was that you only spend money where people can see it. Consequently, the building has no grand interior spaces—no dining rooms or boardrooms, no ballrooms or auditoriums. It was built to be as functional and businesslike as possible.

Inside, the first floor—which is actually the third floor due to the elevated roadway—had a modestly scaled entry lobby with a vaulted ceiling and six elevator banks that occupy about one-third of the total square footage. (The rest was left open for retail tenants.) The original floor was marble, and the original plaster walls had a minimal amount of Spanish Renaissance detailing. The only hint of extravagance were the bronze fittings by the Chicago Ornamental Iron Company, another firm with a long history of partnering with Burnham and Graham, Anderson, Probst & White on various projects. The company’s contributions to the interior include the elevator doors, two chandeliers, a mail chute, and a clock suspended from the ceiling. The upstairs hallways, meanwhile, had marble floors and wainscoting and mahogany doors but were otherwise unadorned.

A work of staggering beauty

Great buildings are always revelatory, not only about the hopes and dreams of their makers but also about the cities where they are located.

“Anyone can make gum,” William Wrigley Jr. famously said. “The trick is to sell it.”

Chicago was the ultimate mercantile city and the Wrigley Building was conceived as a tribute to salesmanship. But it was also a place where a group of artists and craftspeople came together to create a work of staggering beauty and complexity.

That has always been the sustaining tension of Chicago architecture: art in the service of business and business in the service of art.

And then, every so often, a building comes along that expresses this formula so perfectly that it becomes what the Wrigley Building is—a beloved landmark and a symbol of a city that dares to dream big.

Adapted from The Wrigley Building: The Making of an Icon, by Robert Sharoff, William Zbaren, Tim Samuelson and John Vinci

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

.jpeg?width=1200&auto=webp&trim=0,100,0,100#)

![Big Brother Recap: Rachel’s HOH Sends [Spoiler] Packing](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/big-brother-live-eviction-week-6.png?#)