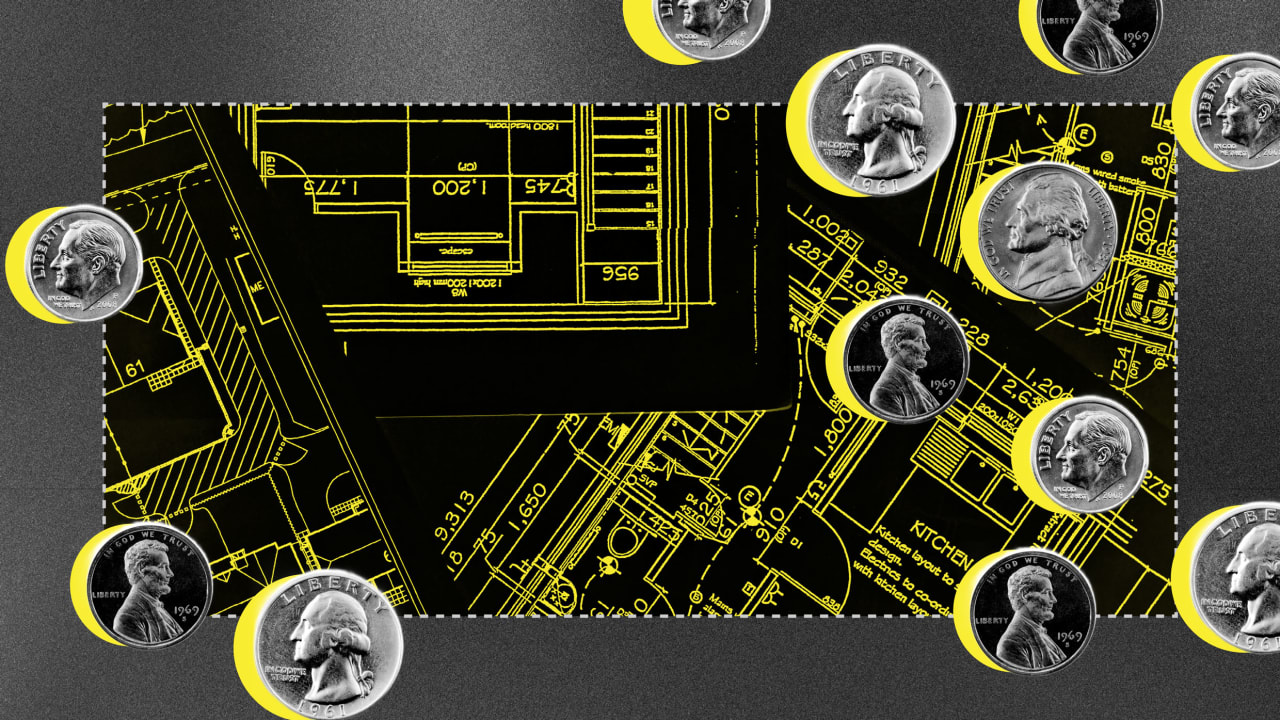

Why are architects so underpaid? Here are 4 reasons, plus one way to fix it

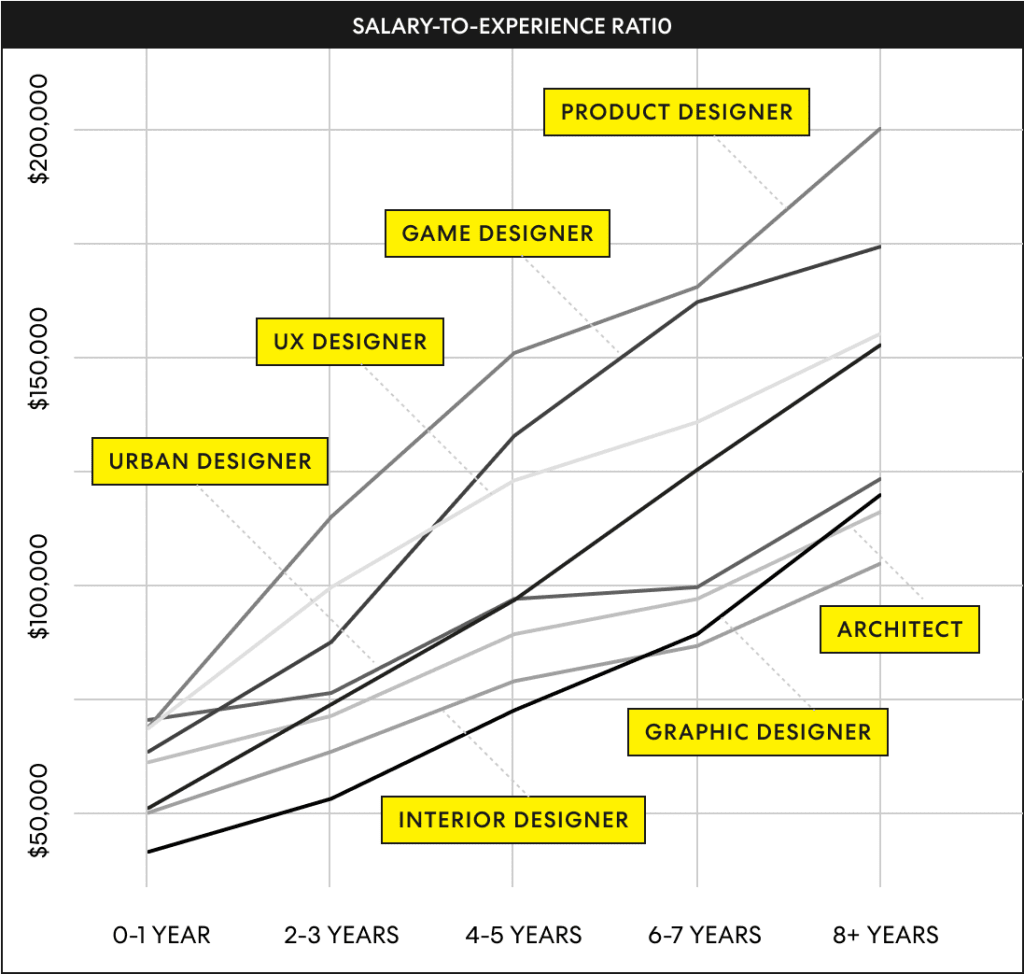

Architects have long complained about the industry’s relatively paltry pay. Given the amount of expensive education architects require (master’s level), and the years they have to put in (many) before qualifying to take a licensure exam (arduous), they have been rightly upset: Architects can barely expect to crack the $100,000 salary mark after more than eight years in the profession.

Now there are some numbers to back that up. Compared to every other design descipline Fast Company has studied in our our ongoing analysis of where the design jobs are, architects are underpaid, particularly as their careers progress. Their compensation increases at the slowest rate, based on years of experience.

Fixing the problem requires a nuanced understanding of the outside factors that limit pay, according to Evelyn Lee, president of the American Institute of Architects. “Architecture is an industry that’s always been known to work within tight margins,” she says. Part of the reason is that the industry long ago set standardized fee structures—basically a percentage of overall construction costs—and those numbers haven’t changed much. “Our ability to get paid more is tied back to that,” Lee says.

Architecture is also tied to economic cycles, and it can be a bellwether of recessions. “When things are good, and people are spending a lot of money on capital costs, we are doing well. But we’re usually the first service to get cut when people start to hold back, and we’re the last to come on board when the economy starts coming back,” Lee says. And because they’re never quite sure when the next project will come around, many architecture firms end up being conservative with their spending and salaries.

Also, the highly competitive nature of the architecture industry means that it is governed by antitrust laws that prohibit price fixing. These laws are meant to encourage competition, but they often end up creating a race to the bottom. Firms underbid each other in order to secure commissions, and then rely on underpaid workers and uncompensated overtime to get the job done. “It’s very internalized in the profession, starting at the university level,” says Jennifer Siqueira, an architect at New York-based Bernheimer Architects who helped organize the first union at an architecture firm in the U.S. “You’re taught to work very hard because it’s like these are passion projects. It’s almost an artistic endeavor to do architecture . . . It’s a very exploitative environment.”

All-nighters are common in the field, from university through the working world; Siqueira says that she herself worked through the night multiple times in previous jobs at architecture firms, including some that are very prominent. Part of the unionization effort she led at her current firm was centered around improving working conditions and making the level of pay match the level of effort. She and fellow union organizers even negotiated with the firm’s management to set salary floors based on years of experience. “It’s very rare, especially because in a lot of contracts you’ll see a clause saying you can’t even talk about what you make to another coworker,” Siqueira says. “This is a level of transparency that’s really lacking within the profession.”

Lee, at the AIA, says that the association conducts its own compensation surveys in order to fill that void, but she explains that the upwind forces that limit architects’ fees and salaries are largely beyond the industry’s control. Still, that doesn’t mean architects should sit back and wallow in low fees forever. She says that the AIA has increased the number of training programs it provides that are geared toward the business side of running architecture firms, and it encourages architects to be more proactive in offering clients more than just the limited scope of a one-off building design. “I do think there’s an opportunity to get more savvy though about how we package and deliver our services in a way that better reflects the value that we bring to the table,” she says.

Changing an industry takes time, especially one that is predominantly made up of small businesses. About 75% of the 19,000 architecture firms operating in the U.S. have 10 employees or fewer, and 28% are run by sole practitioners. Architects are “wearing many hats, as the marketer and the operations person,” Lee says. Other types of designers work within “a much bigger ecosystem, where they have business experts that are brought on to support non-project needs. We architects feel like we have to do that all on our own.”

Lee, who has worked as a fractional chief operating officer for multiple small and medium-size architecture firms, says that the AIA is “trying to support our architects and tell them that it’s just as important to design their business as it is to deliver design as a practice.”

But that may take longer than some architects are willing to wait. In the meantime, Siqueira says there’s a clear path toward improving pay and working conditions for architects: “The only way is to unionize,” she says.

This article is part of Fast Company‘s continuing coverage of where the design jobs are, including this year’s comprehensive analysis of 170,000 job listings.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0