Why did 9,000 of Philadelphia’s municipal workers go on strike?

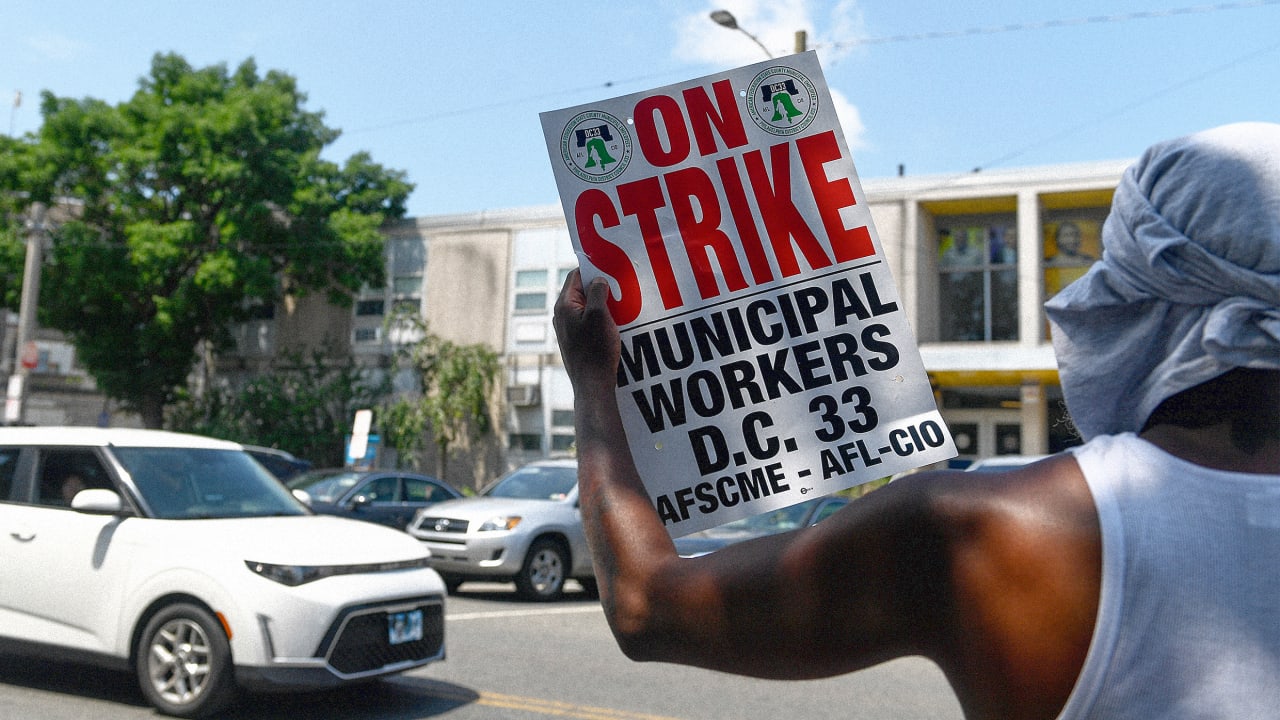

On July 1, more than 9,000 members of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME)’s District Council 33 in Philadelphia went on strike. The work stoppage entered its second week with no end in sight, but a marathon bargaining session resulted in a 4 a.m. tentative agreement between the union’s leaders and the city on Wednesday, July 9.

While Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle Parker has tried to spin it as a win for the workers (and has embraced it as a victory for her administration), some union members’ public reaction to the deal has been far from positive. On Monday, July 14, they’ll vote on whether to ratify the new contract, and the outcome is currently anyone’s guess.

The union—known better as DC33—represents the city’s blue-collar municipal workers, who handle a wide range of job descriptions—from 911 dispatchers to library assistants to water department employees. Perhaps most notably, it also represents thousands of sanitation workers, and it’s that group in particular that became the most visible symbol of the strike due to the nature of their work—and the visceral ramifications of their work stoppage. As the sixth-largest city in the U.S., Philadelphia generates a lot of trash. And with the trash collectors on strike, things quickly got ugly.

Enormous piles of trash popped up all over the city once the workers walked out, spilling out of the city’s designated temporary drop-off centers and onto the city’s streets and sidewalks. In an unflattering homage to Mayor Parker, who became the face of the city’s fitful negotiations with the union, some residents dubbed the garbage heaps “Parker piles.” Thanks to soaring temperatures, spiking humidity, and heavy rain, residents complained that the stench was becoming a serious problem before the agreement was reached.

So how did the city get here?

DC33’s most recent contract expired at midnight on July 1, following a one-year extension that the union agreed to at the beginning of Parker’s term in 2024. While the mayor’s office indicated a willingness to continue bargaining, the union’s leadership decided to call a strike, determined to secure a meaningful economic boost for their members. This marks the first time DC33 has hit the bricks since 1986, when workers stayed out for three weeks, and 45,000 tons of garbage towered over the streets.

The primary issue is money: Members of DC33 are the lowest paid of the city’s four municipal unions, as well as the only one with a predominantly Black membership; the other three include AFSCME DC47, which is made up of white-collar city workers, and the unions representing the city’s police officers and firefighters.

The average salary among DC33 members is only $46,000 a year, which workers have decried as poverty wages. (Sanitation workers, by the way, generally take home about $42,000 a year, and Philadelphia’s sanitation workers are among the lowest-paid employees in the country despite serving a city of more than 1.5 million residents.) Those numbers place them well below a living wage for Philadelphia, which the Massachusetts Institute of Technology calculated as $48,387 for a single adult with no children.

The union was most recently asking for a 5% yearly wage increase over a three-year contract, but the city refused to budge from its own proposal of 2.75%, 3%, and 3% increases over that same period—only inching up to a 3% first-year raise in the tentative agreement. The city of Philadelphia currently has a budget surplus of $882 million, from which the mayor budgeted $550 million to cover all four city workers’ union contracts. The cost of the proposed DC33 contract will be $115 million over its three years.

In contrast, Parker’s current budget proposal has already bookmarked $872 million for the Philadelphia Police Department, a $20 million increase that includes $1.3 million for new uniforms.

City officials touted their lowball offer to DC33 as a sign of fiscal responsibility, but even now that bargaining has ended, union negotiators and their membership remain adamant that it’s just not enough.

There were other issues at play, too. Unlike other city employees like police and firefighters, DC33 members are required to live inside the city of Philadelphia—which, given the rising cost of living, only adds to the economic pressures they face. The union sought to remove the residency requirement in order to give their members more flexibility, but the city ultimately shot down their request. In addition, the union fought to preserve and improve members’ healthcare and pension plans, and saw some success.

With an embattled mayor facing criticism over her own staff’s lavish salaries and mixed results on her campaign promise to make the city “safer, cleaner, greener,” the city took an increasingly combative posture toward the union. Multiple injunctions forced certain strikers (like those at the airport, the medical examiners’ office, the water department, and the 911 dispatch center) back to work, while the city paid private contractors to clear the trash drop-off sites and called in non-union workers to perform union labor.

Meanwhile, DC33 maintained picket lines outside libraries, sanitation centers, and city buildings during a week of sweltering heat. Workers danced, sang, marched, set up impromptu cookouts, and waved signs at passersby. The Wawa Welcome America concert on the Fourth of July lost both of its headliners, LL Cool J and Jazmine Sullivan, who both canceled their performances in solidarity with the strikers. There was also tragedy: Two striking DC33 workers, one of whom is pregnant, were the victims of a hit-and-run last week when an intoxicated individual drove into their picket line; Tyree Ford, a sanitation worker and father of four, sustained serious injuries and is still in critical condition.

Ultimately, the city’s strong-arm approach led to the current tentative agreement, which falls far short of what the workers wanted and is not guaranteed to survive the membership vote. Union leadership has been open about its own disappointment, too. “The strike is over, and nobody’s happy,” Greg Boulware, president of DC33, told The Philadelphia Inquirer as he left the marathon bargaining session. “We felt our clock was running out.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0