With ICE crackdowns on the rise, private prisons are booming businesses

Within apartment complexes, workplaces, and courtrooms, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers have forcibly detained more than 50,000 people in the first six months of 2025. These people, some of whom were reportedly detained for matters as trivial as a single missing form, find their lives abruptly uprooted as they are transported—sometimes thousands of miles across the country—to large-scale ICE detainment facilities, which are primarily located in the South and on the East Coast.

ICE currently holds more than 48,000 detainees, though the agency only has funding to support housing for 41,500. Despite that overflow, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem and White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller now want ICE to ramp up arrests to 3,000 per day—and private prisons stand to benefit.

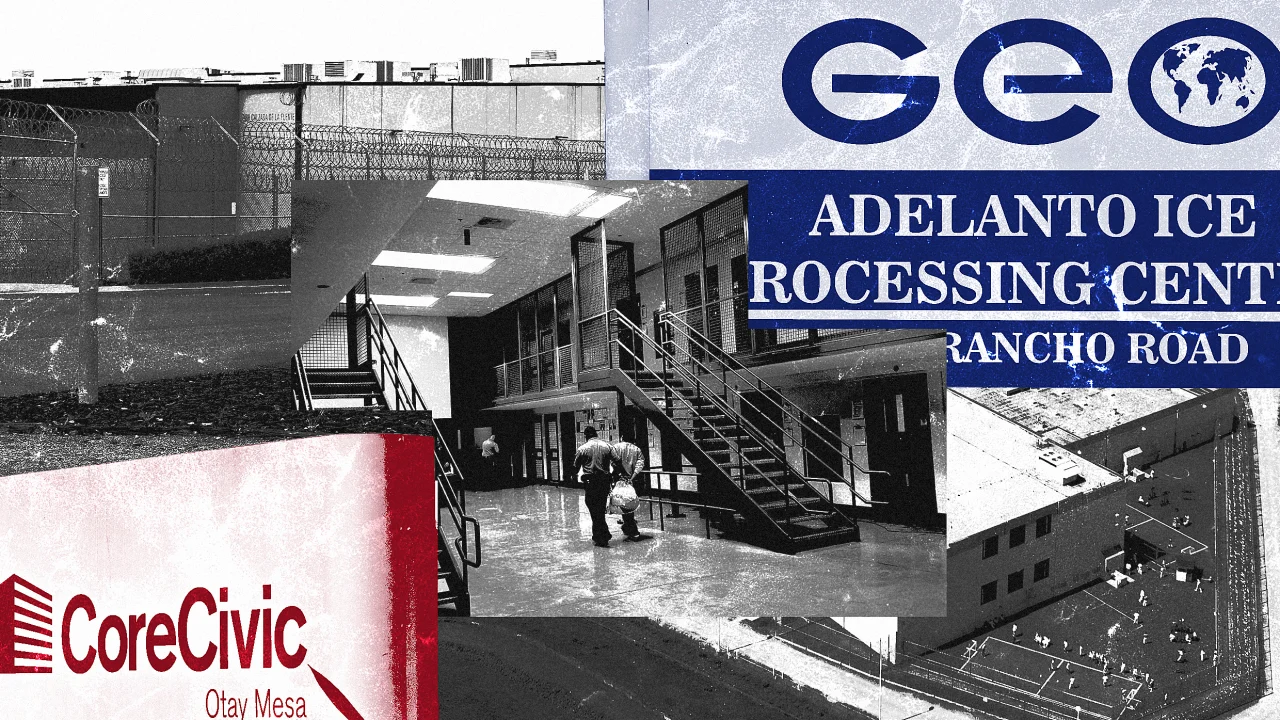

Taxpayers are expected to shoulder the cost of this potential expansion, but the money won’t just go to the government: The majority of ICE’s 113 detention facilities are not government run. More than 90% of immigrants arrested by the agency are held in private detention centers, most of which are operated by just two companies: Geo Group and CoreCivic.

Private prisons occupy a controversial place in the criminal justice system, said Bob Libal, a senior campaign strategist at the Sentencing Project. Beyond general discomfort with the idea of profiting off of incarceration, reports have also questioned safety and security, citing higher incidences of assault, theft, and contraband in private facilities than those operated by the Bureau of Prisons.

Despite their controversial status, private prisons have long been a part of the immigration landscape—and their role is only expanding as the Trump administration makes sweeping changes to immigration policy and enforcemen

The start of the Private Prison Industry

The first modern private prison, Libal says, was CoreCivic’s Houston Processing Center, which opened in 1984 as a U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, and later ICE, detention center. Four years later, cofounder Thomas W. Beasley told Inc. that CoreCivic—then known as Corrections Corporation of America—can sell prison contracts “like you were selling cars or real estate or hamburgers.”

Although federal contracts were a part of the private prison industry from the beginning, it was a 1996 law that cemented their place in the criminal justice system. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 required commissioners to consider buying or leasing existing facilities before building new federal detention centers.

In the 30 years since this law passed—and particularly since the post-9/11 formation of the Department of Homeland Security and ICE—federal contracts have become the industry’s primary growth driver. Last year, federal contracts made up 52% of CoreCivic’s total revenue and 62% of Geo Group’s, much more than the revenue received by state and international contracts.

“The federal government never built their own capacity,” said Lauren-Brooke Eisen, a senior director at the Brennan Center for Justice and author of Inside Private Prisons. “They relied on these companies to do that.”

A Growing Partisan Divide

Federal reliance on private prisons grew substantially under both Democratic and Republican administrations, but there has been a sharper partisan divide in the industry in recent years.

Presidents Obama and Biden each passed legislation to phase out private prisons during their terms. The Obama administration worked toward ending all private prison contracts except those undertaken by ICE, and the Biden administration vowed not to renew any private prison contract. These measures, later rescinded by the first and second Trump administrations, responded to safety and security concerns in private facilities, where differences in contracts and levels of oversight mean standards can vary not only by company, but by facility.

“It makes it very easy for there to be a pass the buck situation,” said Jennifer Ibañez Whitlock, senior policy counsel at the National Immigration Law Center, noting that government agencies awarding contracts may not have enough presence in private facilities to identify problems, let alone address them.

Reports about ICE denying basic medical care to detainees have filled the news recently. Rümeysa Öztürk, a Tufts University PhD student detained in March, said her asthma attacks worsened after not receiving adequate medical care or opportunities to access fresh air while in detention. Similarly, Maria Isidro, a Florida resident detained during a routine check-in with immigration officials, has been shackled and denied medication for her diabetes in an ICE facility in Texas. “We really don’t have a full sense of the scope of it, except for on the occasions that people are released by ICE and can describe to their community or to the media,” Whitlock said.

Still, these concerns and the legislation by Democratic administrations did little to stymie the industry’s growth. The Geo Group, for example, has had relatively steady growth in its U.S. secure services sector, a part of the business including ICE facilities. That sector’s revenue increased from $600 million to $2.4 billion between 2004 and 2023.

A new era of Unprecedented Growth

After Trump spent the 2024 campaign promising to initiate immigration crackdown (a deciding factor for many voters in the 2024 election), private prisons expect their growth to reach new heights in his second term.

Both Geo Group and CoreCivic have disproportionately supported Republican campaigns in most election cycles, but in the last election cycle, Geo Group was also the first company whose political action committee reached its contribution limit donating to the Trump campaign.

Their loyalty seems to have paid off, with Geo Group’s stock price surging from $14.18 to $25.36 during the week of Trump’s election last year, and CoreCivic seeing a similar rise, from $13.19 to $22.52.

“Never in our 42-year company history have we had so much activity and demand for our services as we are seeing right now,” CoreCivic CEO Damon Hininger told investors on the company’s first-quarter earnings call last month.

Both CoreCivic and Geo Group also donated $500,000 to Trump’s inauguration, which CoreCivic spokesperson Brian Todd told Fast Company was “consistent with our past practice of civic participation, including contributions to inauguration activities for both Democrats and Republicans.”

The Geo Group did not respond to a request for comment, but has expressed its willingness to support the new administration’s goals and has stressed the significance of Trump’s immigration policies for the company.

“We’ve taken several important steps in anticipation of what we expect to be significant future growth opportunities and related operational activity during 2025,” Geo Group CEO J. David Donahue said on the company’s Q1 earnings call last month.

Private detention’s expanding impact

Already, ICE has awarded a 15-year, $1 billion contract to Geo Group for a 1,000-person detention center in Newark, New Jersey—the first of several idle private facilities that may be reopened to accommodate the influx of detainees under Trump officials. Within a week of the reopening, Newark Mayor and gubernatorial candidate Ras Baraka was arrested for trespassing during a weeklong protest at the facility. His office previously filed a lawsuit, alleging the facility had not obtained proper permits before reopening.

Tom Homan, Trump’s “border czar” and a former consultant for a division of the Geo Group, has said the administration plans to increase the number of immigrant detainees from 48,000 to 100,000. Another boon for the private prison industry, given the average cost of around $165 per detention bed.

In this time of transition, Geo Group’s and CoreCivic’s stocks remain well above their preelection price, and concern among researchers and activists continue to rise.

“Every detention bed is a person whose life and family and community are likely to be impacted,” Libal says. “It’s another story of somebody who’s dropping their kids off at school who was picked up by ICE and now is in a detention bed.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0