Ford has a vision for the office of the future, and it starts with this 100-year-old building

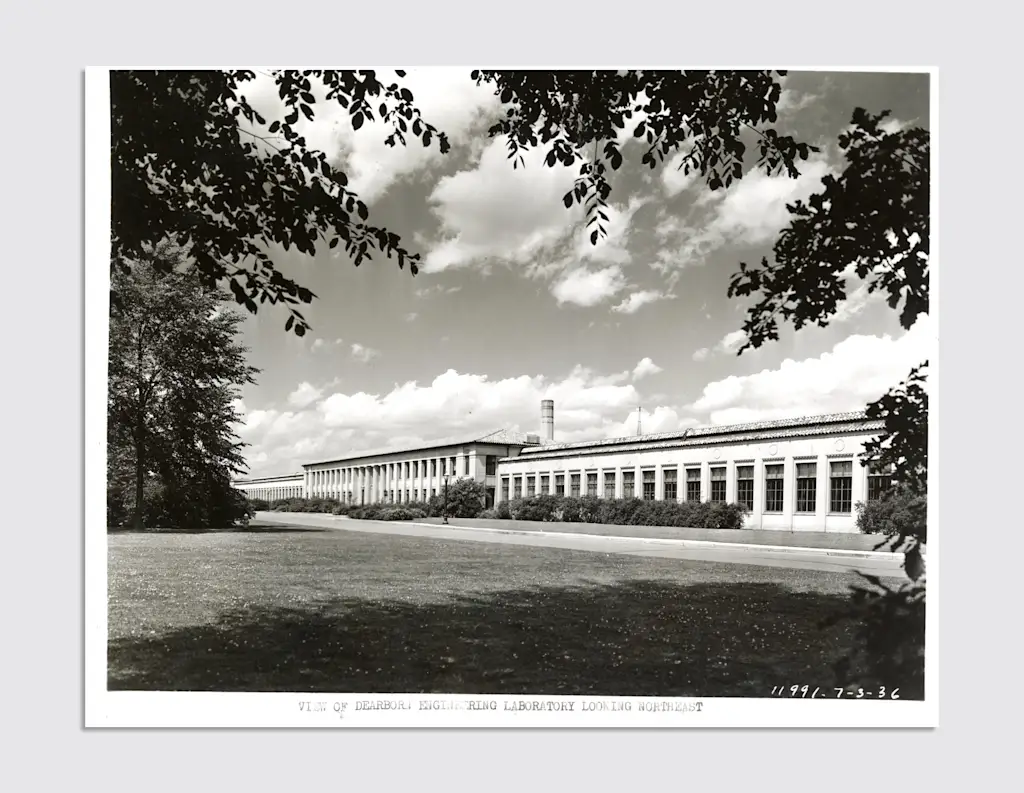

Even though it was built more than 100 years ago, a former engineering lab on the Ford Motor campus in Dearborn, Michigan, is a vision of the company’s future.

The building originally opened in 1924 as a kind of early research and development lab, but Ford has now transformed it into a modern office building that the company sees as a model for its new global workplace standards. With more than 300 million square feet of offices in 46 countries, the approach for this one building will have wide implications for the face of the company, and the workforce it’s able to attract.

The Ford Engineering Lab, as it is still known, is Ford’s version of a post-pandemic, human-centric workplace, according to Jennifer Kolstad, Ford’s global design and brand director.

Sitting on a long curving couch within one of the open collaboration and social spaces in the center of the building, she points out the range of spaces around her. There are small modular meeting rooms, clusters of desks for small teams, café seats, and cushy chairs with side tables that look straight out of a fancy hotel lobby. “Before, Ford Motor Co. was a culture of desks,” Kolstad says. “We have consciously worked to reconstruct the association with how work gets done, which is that work does not necessarily occur at a desk.”

A historic setting for a modern workplace

An architect whose previous work has included luxury hotels in the Middle East and hospitality design for large architecture firms like Gensler and HKS, Kolstad is no office traditionalist. When she joined Ford in 2019, she set out to bring her hospitality experience to bear on a new kind of workplace. “Part of this work is to encourage people to share information, and to want to be together sharing ideas, in order to be more innovative,” she says.

A building from 1924 might seem an odd place for this kind of transformation to begin, but this building was different from the start. Designed by Albert Kahn, the famed industrial architect behind many Ford company buildings and factories, the Lab was intended to spur design innovations by putting ideas people, designers, engineers, and executives all under one roof.

And it’s a big roof. The long, two-story, 221,000-square-foot building has room for hundreds of workers, and the original design pushed the office space to its sides. Along the front face of the building there’s a dark wood-lined hallway the company calls Mahogany Row. (Fact check: It’s actually walnut.) Down this hall were the highly prized private offices that executives clamored for when this building originally opened, complete with picture windows to the outside and large anterooms where their personal secretaries sat.

At the end of Mahogany Row are two larger adjoining offices, one for company founder Henry Ford, and the other for his son, Edsel. The Fords’ offices have been carefully preserved—this was the elder Ford’s last office at the company before his death in 1947—but the rest of the spaces on Mahogany Row are now history-tinged conference and meeting rooms, updated with modern equipment and furnishings.

On the other side of that hallway, a door leads to a light-filled open plan space, with a double-height cavern running down its spine. That double-height space, like a top hat on the building, is lined up and down with large skylights that pour daylight throughout. This facility has the DNA of the archetypal Henry Ford assembly line, and it sometimes worked that way. Ford workers could design, engineer, and build full-scale vehicle prototypes all within this one building, the car’s chassis moving through the building while hanging from steel rails that still sit just below the skylights. Ford’s Model A, introduced in 1927, was designed in this building.

The ‘epicenter’ of a newly centralized corporate campus

After many decades of use and several renovations—perplexingly, drop ceilings were added in 1978, blocking out the skylights—the building was decommissioned by Ford’s real estate arm, Ford Land, in 2007. But its history, and those skylights, played a role in giving the building a second life.

The company reengaged the building in 2015, and it was highlighted for renovation in a large-scale master planning effort in 2017. The effort was led by the architecture firm Snøhetta, which is also behind the design of a 2-million-square-foot R&D hub under construction across the street from the Engineering Lab. Instead of buildings that were previously scattered across the low-density suburbia of Dearborn, Ford is centralizing its offices and facilities into a corporate campus. “This is the epicenter,” Kolstad says, inside the Engineering Lab. “For us, there was no question we were going to make use of this building.”

The master plan for rethinking the corporate campus came out in 2019, and also started a process within the company to focus not just on the buildings but how employees use those spaces. Kolstad says the company has embraced the Well Building Standard, along with its evidence-based building design and operation protocols that prioritize human health and well-being. Rather than just thinking of offices as rooms full of desks, the company shifted its focus to environmental sustainability, natural light and materials, biophilic design principles, and the emerging science of neuroaesthetics. “It’s all very core to the way that we’re designing all of our buildings,” Kolstad says.

New design principles take architectural shape in Ford offices

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic kicked this work into overdrive. Rather than waiting to see these ideas take form in the new research and development building that’s still under construction across the street, Ford folded them into the renovation of the Engineering Lab.

Inside the building on a recent day, these principles show up in the varied types of workstations, the formal and informal collaboration areas, the seating, the conference room furnishings, and especially, in all that natural light. Groups of workers could be seen gathering around large screens in quiet conference rooms, while one-on-one meetings were happening at the central café space or on a long library table or on the steps of a grandstand-style tiered seating structure.

On one end of the building, an open floor was peppered with a more traditional layout of individual desks, though even these rows were interrupted with clusters of desks pulled together seemingly ad hoc. “All of it is meant to evolve over time and, frankly, let our employees decide how they want to use the space,” Kolstad says.

‘We better be looking good to them’: Building loyalty among a new generation of workers

When Kolstad joined Ford, part of the job was to reckon with the demographic reality that an estimated 60% of the company’s workforce was turning over within the following decade. “That really struck me because it meant that we were going to have this totally regenerated new younger workforce that had no historical loyalty to the company, necessarily,” she says. “So part of our work is about reestablishing that. We’ve got Gen Z, we’re now moving toward Gen Alpha joining us. We better be looking good to them, and ready for them.”

Kolstad says the Engineering Lab, and the broader workplace transformation underway across Ford’s real estate portfolio, is all about designing for outcomes. She calls the approach “human affordance thinking,” and says every design decision was considered through the lens of improving workers’ experiences. “We were asking the question, do we believe it’s going to sustain a desired outcome, like innovation or collaboration or community building. And if it didn’t, we vetted it, and we didn’t allow it to move forward,” she says.

The efficacy of these design approaches will likely become more clear in the coming months. Ford is instituting a five-day return to office policy in September, up from the current three. Having people in this office building every day will help Kolstad and her team understand how the design is, or maybe isn’t, creating the conditions for those worker experiences and outcomes.

Whatever they learn, she says the building is set up to be able to evolve. And this approach is being implemented in Ford’s other offices around the world, and will even trickle out into its dealerships in the coming years. The goals for the new Ford offices go beyond aesthetics or office amenities, she says, though those are both important. “This is as much about cultural change as it is about physical tools,” she says. “These buildings are just tools.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

![Chris Columbus Reveals He's Working on 'Gremlins 3' [Exclusive]](https://static1.moviewebimages.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/still-from-gremlins.jpg?#)