No more Mr. Nice Guy: The incomparable Michael Bierut steps down

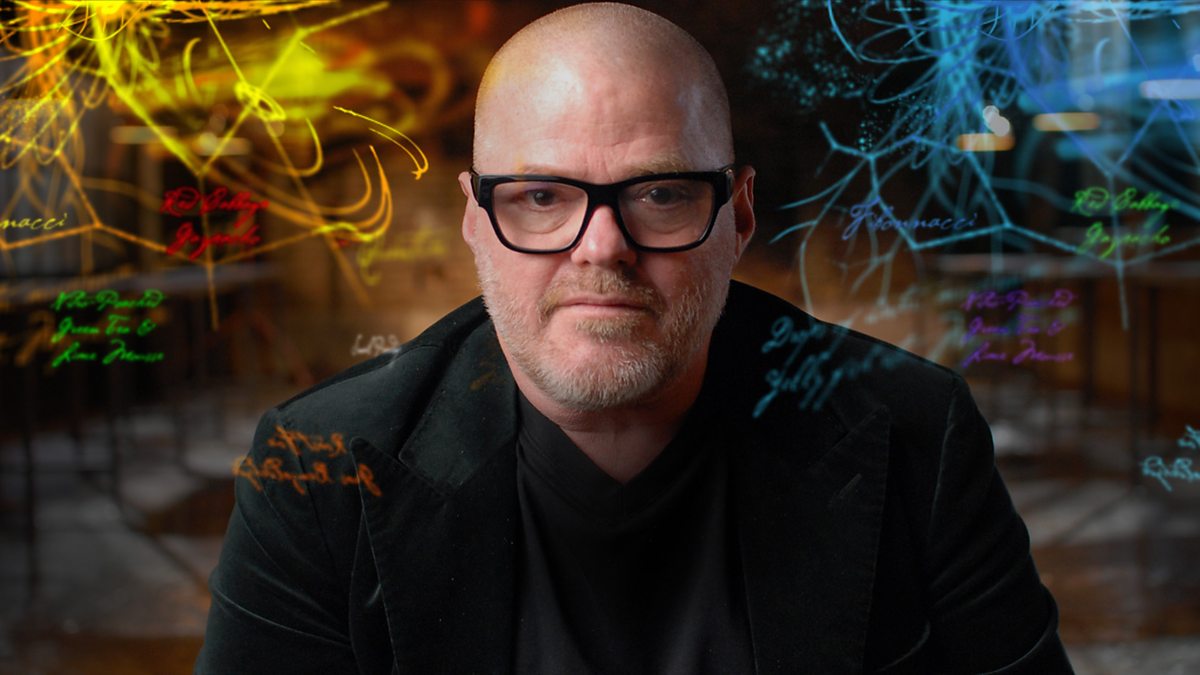

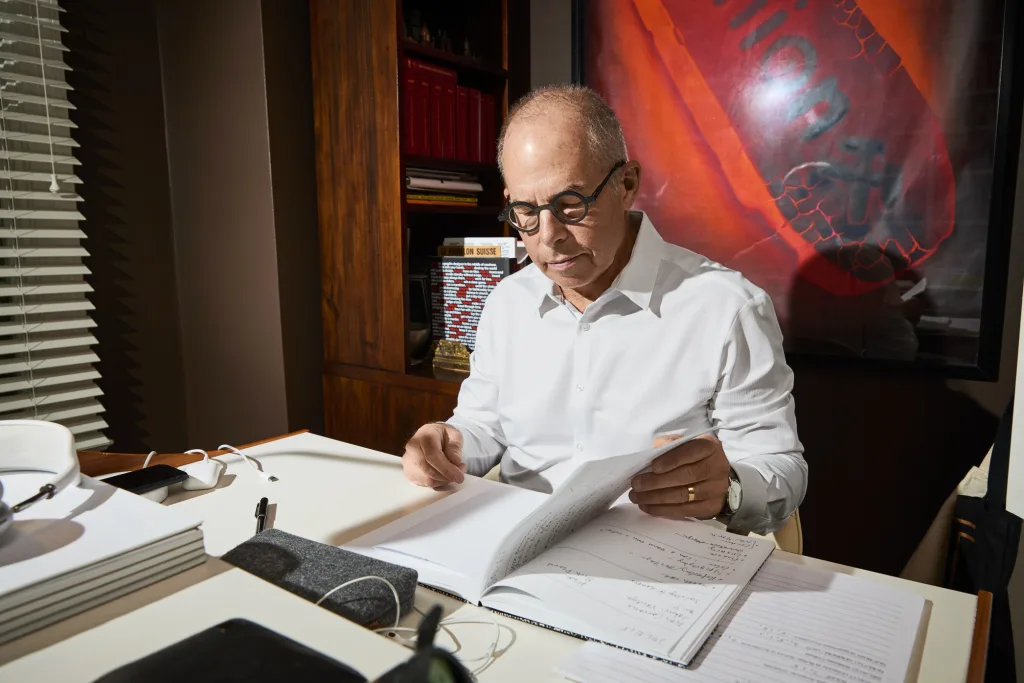

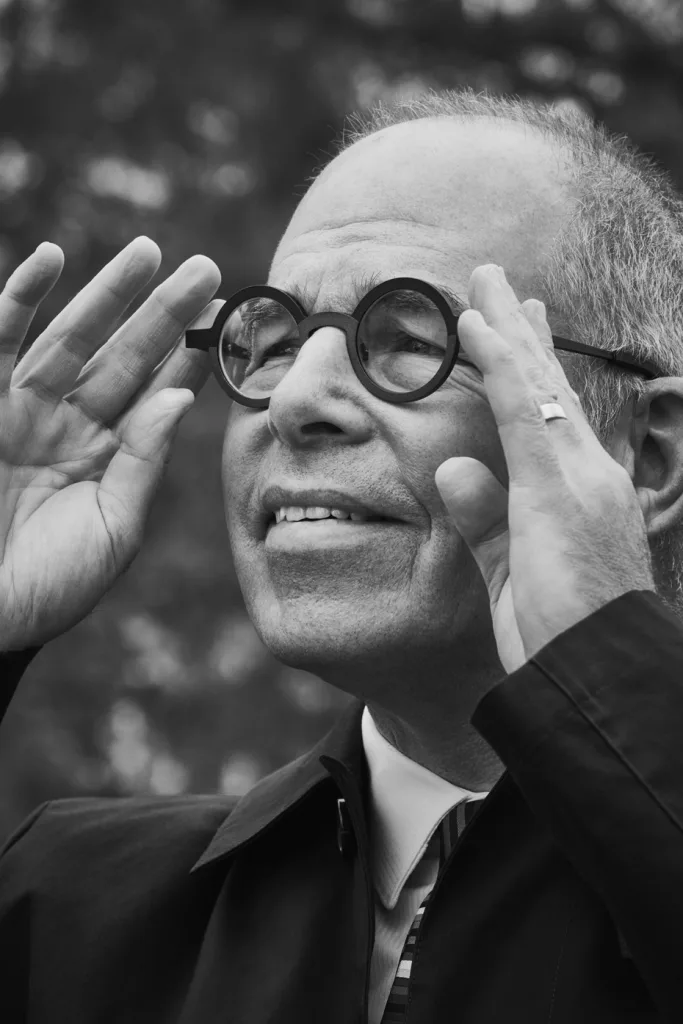

On a Tuesday last fall, Michael Bierut was sitting in his living room in Tarrytown, New York, about 25 miles away from where he’d typically be on a weekday afternoon at any point over the previous few decades.

Bierut, 67, had just stepped back from his role as partner at Pentagram, the storied graphic design studio that has shaped the branding for many of the world’s most important companies, and he was feeling restless.

“It’s been disconcerting for me,” Bierut said as we spoke with a view of the Hudson River sparkling from the window. He noted that the rest of Pentagram’s partners were currently on an annual retreat in an undisclosed location. This was the first time he hadn’t attended. “I’m a really black-and-white person. I have two speeds. I do a lot, or I don’t do it at all.”

For most of his career, Bierut put on a suit and tie, took the Metro-North train from the suburbs to the city, and went to work. Now, he goes to the Flatiron office once a week in his new role as a strategist at-large, where he acts as a part-time consultant on retainer to his fellow partners. Bierut plans to use the rest of his time writing, teaching, and working on independent projects. He has a few ideas for design books.

Bierut has spent the better part of four decades running at full speed. He is responsible for some of the world’s most recognizable logos, including those for Mastercard, Slack, Verizon, and the Hillary Clinton presidential campaign. He shaped the industry from one centered on auteurs executing their creative vision into a more pragmatic and professional ecosystem of work by advocating for the field in business. He launched one of the first design criticism blogs, Design Observer, and is the author of a best-selling design book. He is, by many measures, a celebrity inside of the insular graphic design world, where his approachability and generosity have won favor in an industry that’s often fueled by ego and big personalities.

“If you say ‘who are the famous graphic designers in the world, Michael will probably be in the top five depending on who it is that you speak to, if not No. 1 every single time,” says Aron Fay, a former designer on Bierut’s team.

Bierut has built a career out of being a good guy with great ideas. “He is like the nice guy finishing first in a way,” says Britt Cobb, another longtime designer on his team. But now, Bierut says, it’s time to step aside for a new generation of design leaders who can usher the industry into a new, and more complicated, era.

It’s a telling bookend to a fruitful career that has been driven by unrelenting focus, work, and ambition. “I had this funny combination of insecurity and bravado,” Bierut recalls of himself at the start of his career. “Everything seemed to be affirming that my suspicions were correct that I was the best designer in the world.”

66.5 years old

A few years ago, Bierut received an omen in one of the least mystical forms imaginable: a prepaid business class envelope from the IRS. It was his social security notice. The letter said he’d be fully vested at “66.5 years old,” which happened to fall on leap day 2024. He took it as a sign to retire. “A very typical-for-me thing,” he says.

Longtime Pentagram partner Paula Scher remembers when Bierut told her of his plan. “He told me he was leaving on the specific date that he had made up, that had all kinds of significance between when he joined, or something with Dorothy, his wife,” she says. “I thought, ‘Oh, you’re crazy. You’re never going to do that.’”

Scher was half right.

Ultimately, Bierut couldn’t quite quit. He came back with the strategist at-large idea, which Pentagram partner Abbott Miller says offers a new model for retiring partners to stay on with the group. “He’s a solo agent in this new model, which is fantastic for us because the alternative is that somebody just steps aside and leaves with all of that intelligence and history,” says Miller, adding that the firm previously defined a partner as someone who ran a team. “In the past, it’s been an unceremonious goodbye.”

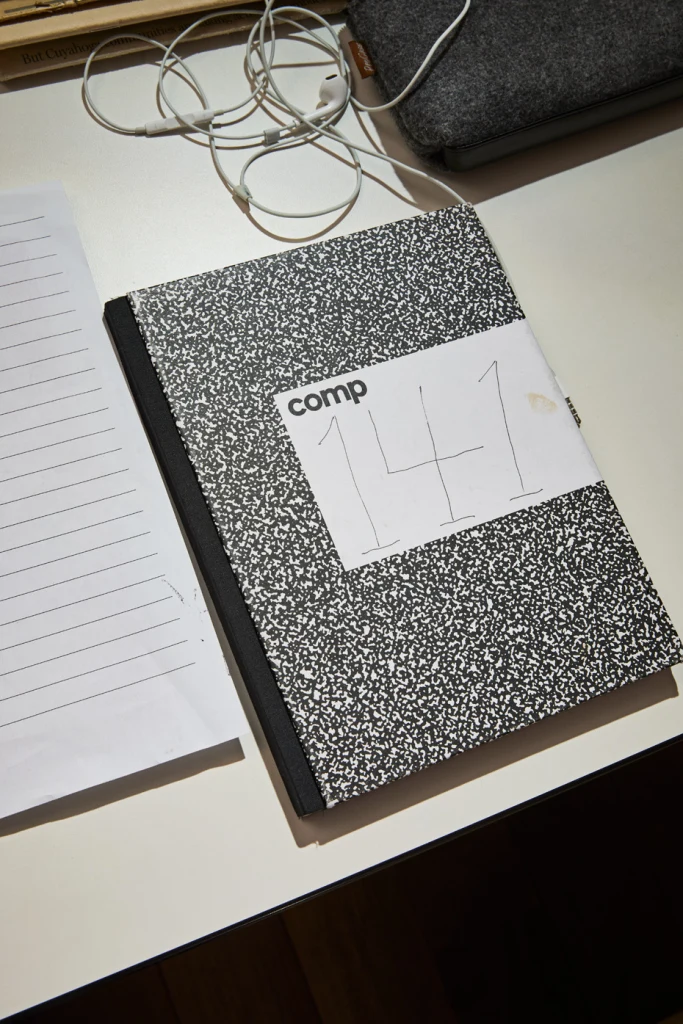

Bierut describes Pentagram as a little like Saturday Night Live: the cast changes, but the show goes on. Even before his quasi-announcement, he’d been feeling like it was time to pass the torch. Bierut, who is known for filling composition notebooks with early sketches of his designs, had started to feel a gap between his core ideas and the most contemporary modes of executing them.

He rattled off half a dozen of his fellow partners. “All of them can do things that I can’t do,” Bierut says. “They have a facility with tools, a more nimble way of thinking with technology. I can do things—communicate in the ways humans do—but in terms of really realizing things, they make leaps that I can’t make.”

Bierut has always conceptualized his ideas with pen on paper; he never made the switch to computers himself. Now AI is further revolutionizing industry work, and the ability to execute digital and motion graphic brand iterations is table stakes as identities become more diffuse in online spaces. He recalls that in annual work presentations with partners, “I went from feeling like an iconoclastic prodigy to feeling like I was heaping up the same old stuff.”

Bierut says his new role allows him to focus on his strengths, which center on ideas rather than execution.

His approach has earned him a unique legacy in the world of contemporary design. He is a descendant of modernism’s masters like Massimo Vigenelli, and a mentor to scores of young designers. This has made Bierut a connective tissue between design’s old guard of iconoclasts and a new cohort of design leaders, many of which came up under Bierut at Pentagram before leaving to start their own studios.

When he made the decision to pull back from Pentagram, he called a few senior team members like Cobb and Tamara McKenna, and then told the rest of the team. They’d recently all gone to a screening of American Graffiti for Bierut’s birthday, and he referred to himself as the townie character driving around with the high schoolers the night of graduation. He didn’t want to hold on for too long. He was nervous about sharing the news.

“I was sort of like a one factory town, and I’m announcing the factory is shutting down,” Bierut recalls. He gave his team members a year’s notice, helped them secure jobs elsewhere, and diverted his big clients to fellow partners. And then, the all-or-nothing guy found himself in liminal space.

Ohio born

Bierut was born in Garfield Heights, a suburb of Cleveland, in 1957, and grew up in nearby Parma. His mother, Anne Marie, was a housewife, and his father owned a business selling printing presses. He has twin brothers, Ronald and Donald. Bierut was an introverted kid. “I used books the way people use phones these days,” he says. “The idea of going somewhere without a book was the most terrifying idea ever had.”

But he had an innate artistic talent, and by high school used his skill as a way to get involved in other things that interested him, like theater and music. As a teenager, he discovered books by Milton Glaser, Armin Hofmann, and Neil Fujita. “I wasn’t fit to be on stage,” he says. “But if I would do the poster, I could go to the cast party.”

In 1975, Bierut enrolled at the University of Cincinnati. Yale-trained Professor Gordon Salchow, who previously taught at the Kansas City Art Institute, had just overhauled its design program in the style of the modernist Swiss Basel school. One of Bierut’s professors, Joe Bottoni, remembers Bierut as having an innate talent. “He had it in him,” Bottoni says. “We just gave him the opportunity to express it.”

The department’s mandatory work-study program brought Bierut to the East Coast for the first time in 1978 with a summer internship at the Boston public broadcast station WGBH. The office, led by designer and Yale professor Chris Pullman, was a high-octane place with a diverse client roster and a casual chumminess that would go on to shape how Bierut cultivated his own team at Pentagram. “It was only three months, but it really changed my life,” Bierut says.

The station was at that time on a growth trajectory to become the largest supplier of content to PBS, according to Pullman, and had about 400 employees. Pullman’s team of about 10, including Bierut, handled design for the organization’s slew of national programming, including Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, which was seen by more than 500 million people. After three months, Bierut planned to return to Ohio to finish college and to his fiancé, Dorothy. But first, he made a stop in New York City.

Tom Sumida, Bierut’s WGBH supervisor, had mentioned earlier that summer that one of his Yale MFA classmates, Peter Laundy, just got hired at Vignelli Associates, the iconic New York firm led by the famous designer Massimo Vignelli and his wife, Lella. This caused some chatter in the office—not from Bierut, though, who only had a vague sense of the firm’s reputation. Even so, when Bierut and some friends took a week-long trip to New York at the end of the summer, Sumida told Bierut to look Laundy up.

Standing at a grimy New York City pay phone, Bierut pulled a note covered in names and phone numbers out of his pocket, dropped some coins into the slot, and rang Vignelli Associates. “I was fairly shameless,” Bierut recalls. “I was in New York for a limited period of time and I thought, I’m going to make the most of this.” Laundy said he was too busy to see him but he could drop off his portfolio. Bierut left his portfolio to be reviewed. The next day, Bierut was back in the lobby of the Vignelli office in hiking boots and a flannel shirt to retrieve it. “I looked like I had rolled off the back of a pickup truck from rural Ohio,” he says.

He gave the receptionist his name. “Suddenly, bounding around a corner comes Massimo Vignelli himself, followed by Peter,” remembers Bierut. “Massimo starts pumping my hand with such enthusiasm and saying things like, ‘So this is the kid. This is that Cincinnati kid, right, Peter?’ and saying ‘Your portfolio is fantastic.” Vignelli and Laundy gave Bierut a tour. “The whole thing happened so fast,” Bierut remembers with palpable amazement. “After some period of time that might have been 30 seconds or 20 minutes, I was standing there with my portfolio wondering what the fuck just happened.” Vignelli offered him a job. He joined Vignelli Associates a year later, after he finished college.

New York Bred

Bierut moved to New York City in June, 1980 one week after graduation. Basquiat, Haring, Warhol: Times Square was still seedy. Punk reverberated in the East Village. The city was seemingly covered with a light dusting of cocaine. When I asked him about New York during that time, Bierut more or less shrugged at all this as not quite as exciting as the Studio 54 era New York of the ’70s.

Vignelli Associates was at its peak when Bierut was there from 1980 to 1990. Vignelli was the industry’s sun; modernism rose and set with him. Look to IBM, American Airlines, Bloomingdale’s, Knoll, and the New York City Subway system map and wayfinding and you’ll see the mark of Vignelli’s pen.

Vignelli and Lella were strict believers in structure and an objective, rational, neutral design approach that anyone could interact with. They also used an extremely limited color and font system: white, red, and black; Helvetica, Futura, and Bodoni. Massimo began his career in Milan, which is close to the epicenter of modernism in Zurich. “So he was very, very influenced by the Swiss graphic designers of that period,” says Roger Remington, the former director of the Vignelli Center for Design Studies at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

Bierut eventually chafed against that rigidity, but first, he thrived.

“He clearly was the golden boy in the Vignelli office,” recalls Rosalie Genevro, the former executive director of the Architectural League of New York, who first met Bierut as a Vignelli Associates client in 1985. Bierut designed all of the League’s graphics, and the pro bono client moved with him to Pentagram in 1990. (He passed the League work to partner Eddie Opara upon his retirement.)

“I remember thinking at Vignelli that I was a bit of a prodigy,” Bierut told me at his home in North Tarrytown, where he and his wife moved to in 1984. “And I was unbelievably ambitious. I would be given the most trivial thing in the world to do, and I would stay up all night to do 20 versions of it for Massimo to look at in the morning.” He adds, “I just couldn’t believe that I had this job. I was very conscious of the fact, also, that most of the time I didn’t quite know what anyone was talking about.”

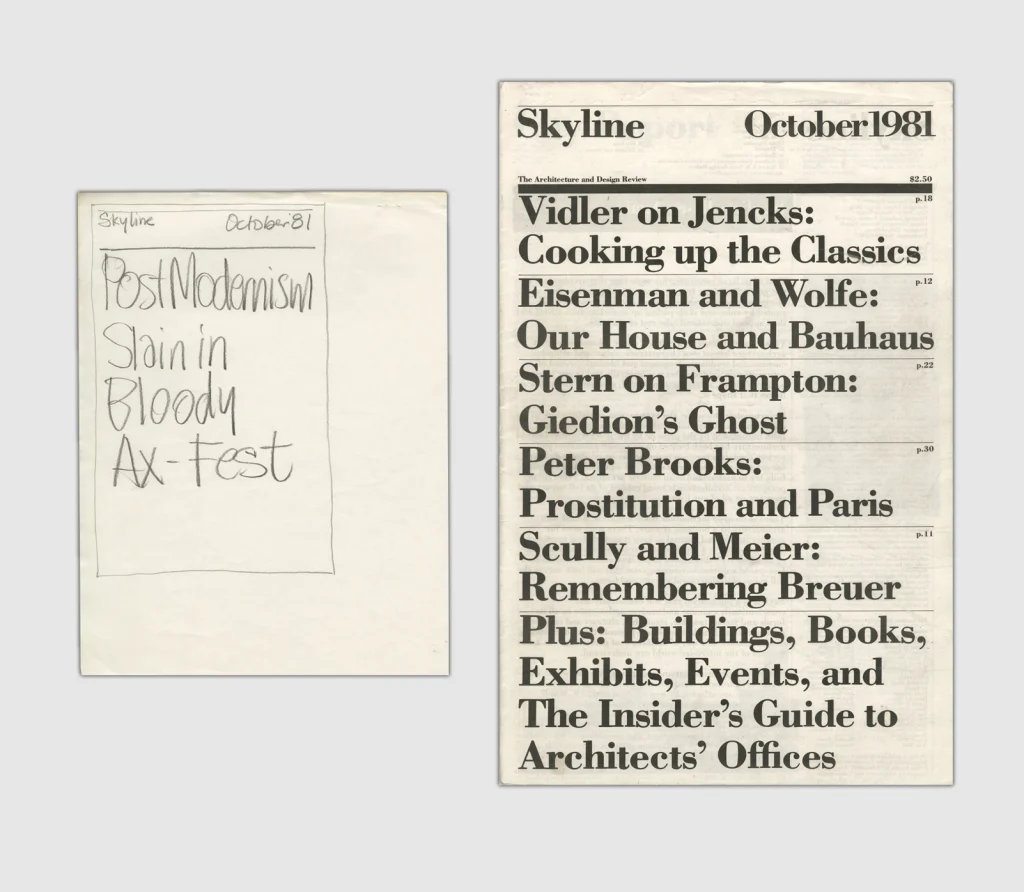

In one such instance, he had to assemble catalogue materials for an Architectural League of New York exhibition and call up a bunch of famous architects to make sure they sent their work on time. He didn’t know who any of them were—but at least that made it easy for him to strong arm, say, acclaimed architect Peter Eisenman into meeting a deadline. But Bierut felt the contrast of his relatively pastoral Midwest background against the Ivy League milieu, and it pushed him to become even more ravenously curious, close the knowledge gap, and prove he could cut it.

Bierut deeply admired Vignelli’s passion, integrity, and deep convictions about design as a potential force for good in the world—that design was inherently a “public-spirited gesture.” By the end of his decade at Vignelli Associates, Bierut had become its vice president of design and taken over as president of the professional organization American Institute of Graphic Arts’s (AIGA) New York chapter. But a curiosity about other ways of doing things nagged at him.

“I knew I was successful at Vignelli because I got the principles,” Bierut says. “But I never thought it was the only way to design something. It was just the way Massimo liked to design, right? I’m a good mimic, but you’re not going to base your life on mimicry. Or I didn’t want to, at least.”

The early Pentagram years

The question came over a plate of steak frites in a dimly lit restaurant downtown. Would he join Pentagram as a partner?

Like many of the designers Bierut hired to join his team whom I spoke to, he knew of Pentagram before stepping foot in the place. He wouldn’t have guessed he’d be considered for the job. But when partner Woody Pirtle asked Bierut if he’d consider joining as a partner following a talk Bierut gave at the firm, he played it cool and said he’d think it over.

The renowned San Francisco designer Michael Vanderbyl, a friend, recalled Bierut asking him to dinner to get his opinion on the move. “I said that yes, he should, because he could emulate Massimo so well, and I was anxious to see what he could do on his own as a designer,” Vanderbyl says. “I encouraged him to do it.”

“I could have been the heir apparent [at Vignelli Associates] I assume, so I had a decision to make when I was 33 years old,” Bierut says. “Do I want to do this forever or do I want to try something new? Just as when I was 66 years old, I had the same decision. Do I want to do this forever? Do I want to try something new?”

Bierut accepted the position.

Now, he was autonomous. There was no one to tell him who to fire, how much to work for. “Like everyone at Pentagram, I pictured how it would be, and it’s never the way you picture it,” Bierut says. “It’s really independent.” He described himself as “unmoored and a little scared and excited” during the early days. He began building a team, securing clients, and finding his own identity.

He started wearing a suit and tie. He became a member of the social club the Century Association, which Mark Twain described as “the most unspeakably respectable club in New York,” according to its website.

Pentagram, founded in London in 1972, is one of the most prestigious international design firms in the world. Following a generation of mid-century firms named after one design hero, like Vignelli Associates, it operated instead as a design consortium of partners who run their own teams and budgets, secure their own clients, and carry their own weight. No matter each partner’s profit and loss at the end of the year, revenue is shared equally. It is built to be a melting pot of ideas, due to its unique structure. Disney, IBM, Coca-Cola, Citibank, SNL, FIFA: It’s hard to capture how broad its portfolio is across global civic, corporate, and cultural institutions. Pentagram’s work is elemental to the way people interact with the world.

Bierut was one in the first wave of second-generation partners who joined the firm, along with Michael Gericke, Jim Biber, and Scher. He helped founding partner of the New York office, Colin Forbes, who was also president of AIGA at the time, beef up Pentagram into the industry heavyweight it is in the United States today by building a roster of large, attraction-getting corporate clients, which complimented the cache-garnering cultural client roster Scher fostered. The firm started to gain attention as a group. Bierut built a reputation for consistently delivering results (though he’s not without his critics).

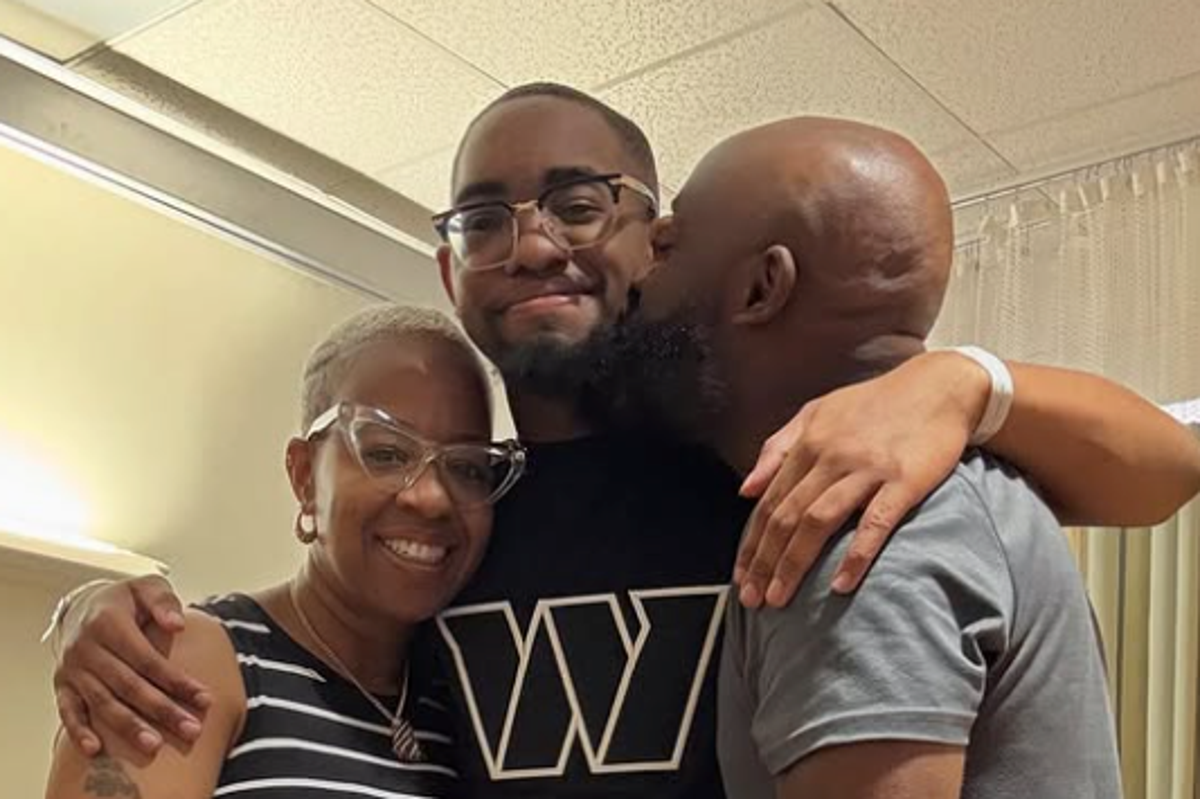

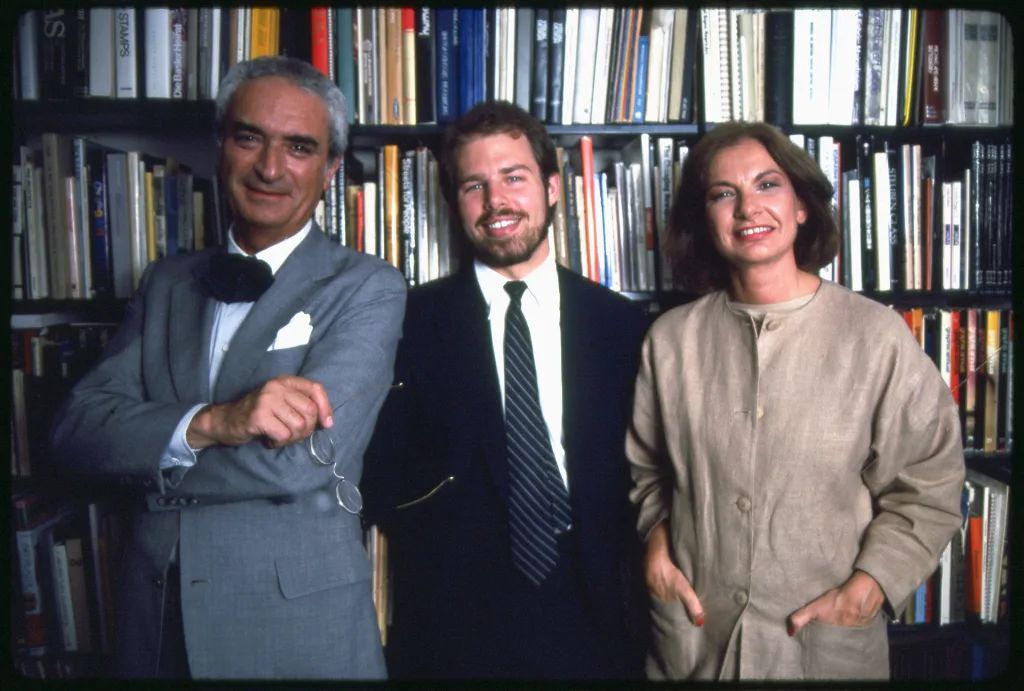

[Photo: courtesy Pentagram]

You’ve seen the work for his biggest clients: the Hillary Clinton presidential campaign, Saks Fifth Avenue, Verizon, Mastercard, the New York Jets, PayPal, Slack, Benetton, the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA), Sesame Street, as well as myriad New York City institutions like the MTA’s OMNY card system, Central Park Conservancy, Governors Island, St. John the Divine Cathedral, the Architectural League, the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), and the Museum of Arts and Design (MAD).

“He’s probably one of the strongest examples of that kind of . . . split that we have between the importance of great work and economic strength,” Miller says.

If you can picture the logo for any of these, know that it probably germinated as a rough pencil sketch from Bierut’s head put to paper in a classic composition notebook (of which he’s filled more than 100 that now line a shelf above his desk), or on the computer monitor of a designer on his team.

Bierut has a seeming ability to conjure an idea like a rabbit out of a hat that lends him an aura of mysticism. In reality, his iterative, in-the-moment ideation process came from Vignelli, who sketched ideas out in real time during client meetings. But without that peek behind the curtain, the skill confounds people. “We would leave the meeting, and he would show me a sketch of a logo or an idea like, ‘This is what they need,’” says Armin Vit, a designer on Bierut’s team from 2005 to 2007 who now runs design firm UnderConsideration. “The sketches were gnarly, like scribbles, but the essence of what we ended up with weeks or months later was there.”

Fay recalls Bierut proposing a solution for Verizon on the car ride home—a gradient checkmark. “He’s like, ‘Oh, I think we should consider doing this.’ Which speaks to the genius of him. He sort of had fully conceptualized the thing after 10 minutes of sitting in a room with them.”

Bierut’s project mix has included pro bono work like for the Architectural League, and small spot illustrations for four-figure payouts, up to larger contracts in the five and six figures. His way of working has helped him retain long-term clients in his roster, like Genevro, who has been with him for decades, as well as corporate clients like Verizon, which brought in six figures over a multi-year contract. (Turner Duckworth rebranded Verizon in 2024.) Scher described Bierut as “very profitable,” and noted that the firm lost a profitable partner when he changed roles, although she declined to cite specific figures. Miller also declined to share specifics.

Finding his own style

It took time for Bierut to shake off some of that Modernist puritanism and develop his own, more humanist aesthetic. “I used to think his design was the least interesting of the Pentagram group in those early days when he was part of it,” says Steve Heller, a former New York Times art director and author of more than 100 design books. “I thought he retained a little too much of Massimo’s austerity. . . . He just had to find his voice, and his voice has always been more diverse than some of the others.”

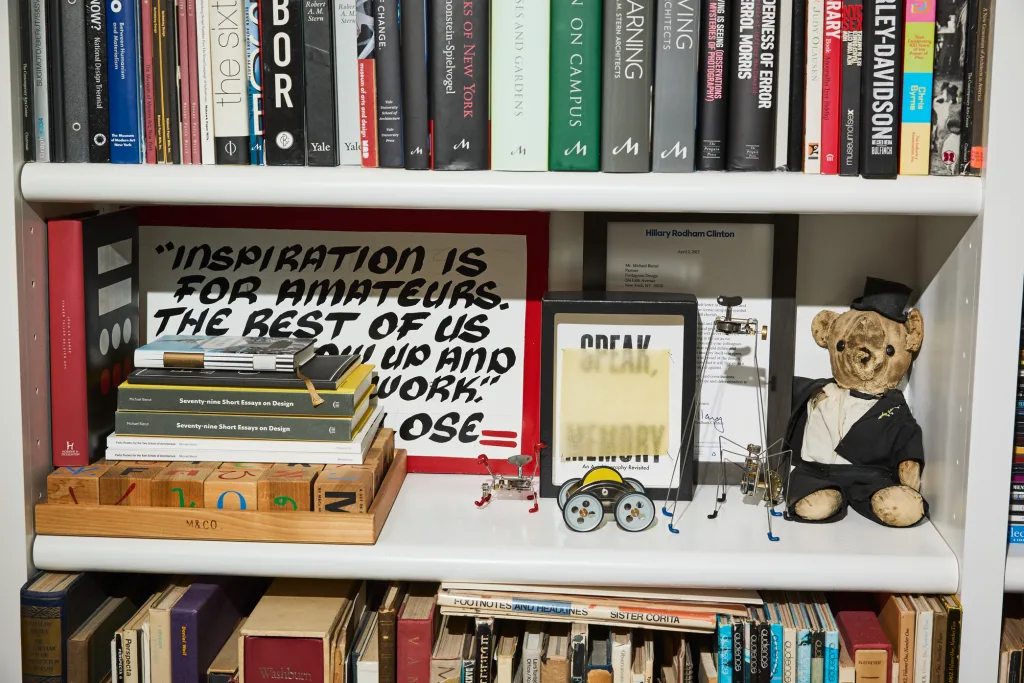

In his tidy home office, among white built-in bookshelves filled with design books and just behind his Eames lounger, Bierut has a framed quote by the artist Chuck Close that reads, “Inspiration is for amateurs. The rest of us just show up and get to work.” His team gifted it to him in the 2010s. The quote also opens his 2015 book How To. It’s a useful artifact to understand how Bierut thinks. He doesn’t see design as an absolute or stylistic ideal. Unlike fine art, it’s not a medium for self-expression.

This makes placing Bierut within design history difficult to do. There are some graphic inspirations, sure, like Fujita or Hofmann. But to really trace his design style, you have to turn to an architect: Ero Saarinen. Saarinen, who died in 1961, designed JFK’s TWA Flight Center (now a hotel), the St. Louis Gateway Arch, the CBS Building in New York, and the GM Technical Center in metro Detroit. None of them look much like each other. Bierut describes Saarinan as a “journeyman,” who felt you had to “find the right style for the job,” and he takes inspiration from this positioning. According to Bierut, the design style is always, “What would make sense for this particular thing?”

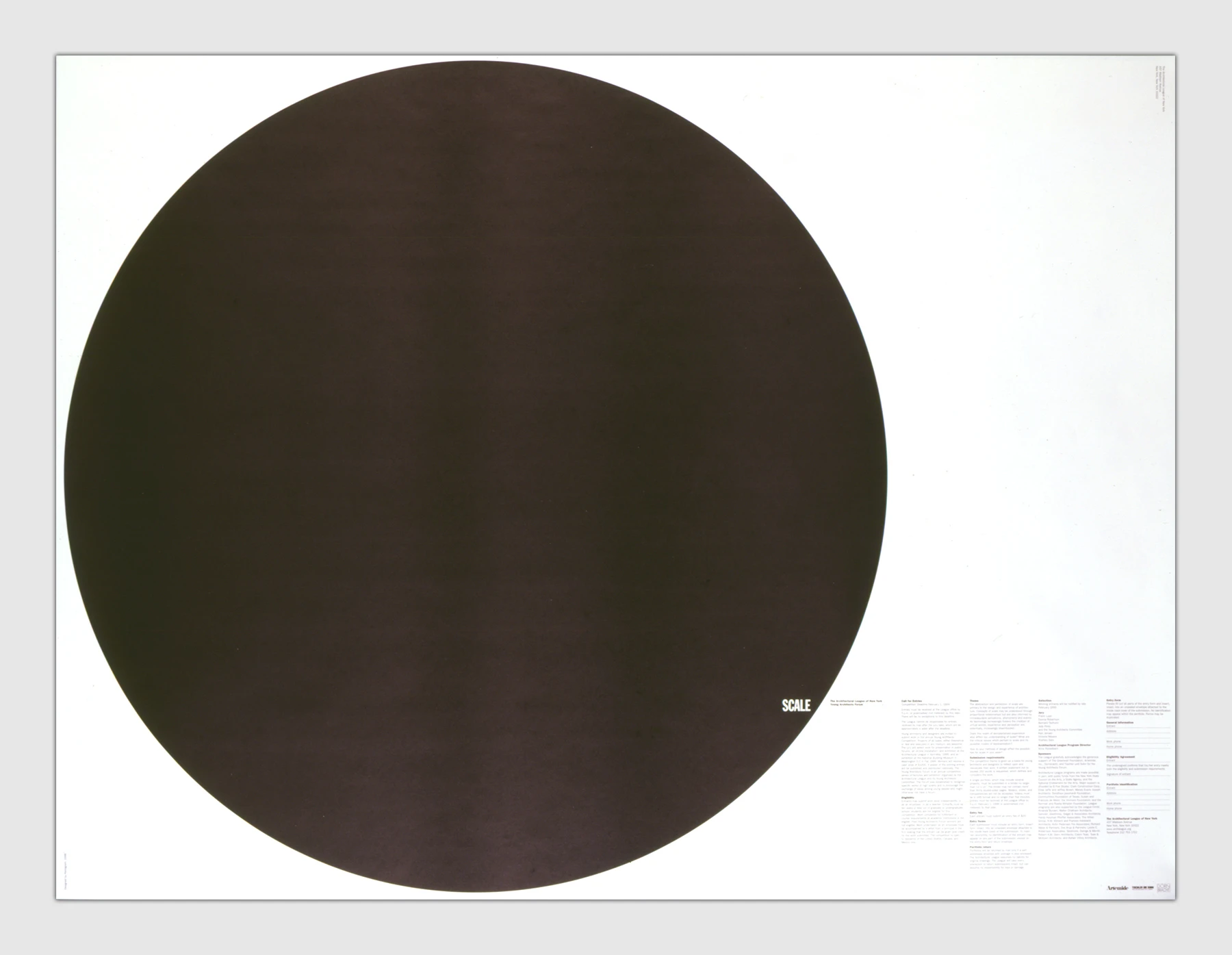

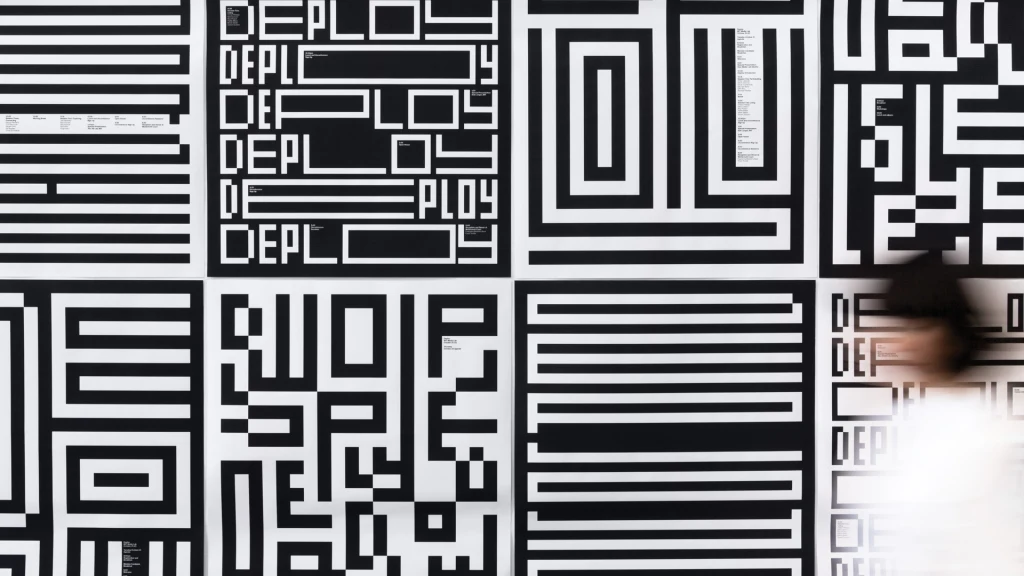

But Bierut does have a few stylistic tells. He returns again and again to black and white compositions and simplified, big graphic moves, which he often iterates, multiplies, remixes or cuts off, as was the case for his 2007 Saks Fifth Avenue rebrand, which rotates and crops a contemporized version of its classic script logo into 64 squares. MIT Media Lab had a core black and white logo with some 40,000 permutations. (Bierut says it’s the one icon designers really “fetishize.”) Or his long-running, conceptually diverse, black-and-white Yale Architecture poster series, which Scher, Heller, and Miller all cited as among his best work.

“Michael is this incredibly conceptual thinker,” says Miller. “He has a reputation as an incredible strategist and corporate identity person, but he thinks in this very deep way about the issues of scale and typography.” A poster Bierut designed for the Architectural League of New York in 1999, which shows a nearly full-bleed black circle with the teeny tiny word “scale” in its bottom right exemplifies this, according to Miller. It’s a quick study in wit. What all his successful projects have in common is a simple, clever, hook.

“He might kill me for saying this, but there’s no one logo that Michael did that you like as the epitome of logo design,” Vit says. “But there’s so much work that is so consistently good at a level that is always appropriate, it’s always well-executed, it’s always relevant. . . . That’s what’s most impressive.”

Graphic design is a pas de deux between the written word and image. “What got me into graphic design originally was about words more than anything else,” Bierut notes. For him, corporate identity design, or branding, as it’s often known today, is a visual expression of problem-solving.

“I remember thinking, design training has a way of refining your sensibility to the point where you’re attuned to things that most people aren’t aware of; where you’re doing work at registers that are going to be barely perceived by people; kind of working the math of really small differences and all these things that you’re going to be really picky about,” he says. “I always remembered, my mom wouldn’t know the difference between any of this stuff. And for certain things I was doing, my mom was the audience.”

The Design Dad

Bierut’s team remembers him as uncommonly generous with his time, even though, in their words, he wasn’t particularly available, and generally doled out time in minutes, not hours.

“We sort of lovingly would refer to him as being ‘Design Dad,’” Fay says.

Bierut typically hired designers after they had a trial run as interns. “In design you have strong-minded people, and I was really fortunate that I seldom had to hire full-time designers who I didn’t already know,” he says. This also had a side effect of creating cohorts of people who were all around the same age and over long hours and takeout, became friends.

He looked for people who had innate curiosity and interest “in all of the ins and outs of a project,” and then he gave them outsized responsibility. At the start of a project, he would assign one designer as the lead—something he learned from Vignelli—and guide them through the initial decision-making about the design concept and direction. From there, he handed off basically everything leading up to a client presentation, with his guidance when needed. “I don’t have to sit at their desk and help them pick a typeface,” he says.

In the early days, Bierut often returned from a client lunch with a logo or identity scribbled on a napkin and handed it to someone to execute, according to Agnethe Glatved, a designer on his team in the early 1990s. In later years, more experienced designers recalled him as being less prescriptive. “Generally, he allows designers to run with the idea from start to finish, build it out, lead it, and that helps build their confidence,” former Pentagram employee Talia Cotton says. “That helps make them feel like they’re creative and they’re being heard.”

The one-on-one relationship between a designer and clients also created a self-running system based on institutionalized trust that allowed Bierut the time to move on to the next project, and leave the office for client and new business meetings, with a shared understanding that his team would deliver. “You look back and you see all these patterns,” Bierut says. “Massimo would travel a lot. He’d give me a project and go to Milan and would come back in two weeks and say, ‘How’s it going?’ Every partner has a way of working that I suspect has root in how they came up in design.”

The model required long hours from a high-energy twentysomething hire who could work independently and be married to the job. Many designers I spoke with said a typical workday ended between 8 p.m. and 10 p.m., or later. They ordered dinners to the office. The team often worked weekends, not because Bierut explicitly required it but because of the caliber and quantity of work they were responsible for.

“Everyone is scared that they’re gonna fuck something up and as a result of fucking up, ruin Pentagram’s reputation, and as a result, their career,” says Cobb. “So that magic makes people work really, really hard there. Michael never has to motivate anyone.”

[Photos: courtesy Pentagram]

In the early years, Bierut was often away at meetings, and his team members could tell when he found Wi-Fi because they’d all start getting emails. Whenever he was in the office, there’d also be a long line of people waiting to get his take on their work so they could keep going. Even so, former team members remember him as extremely present and encouraging. Occasionally, if he spotted a really killer design on a monitor, he’d slow clap from partners row, a second floor overhang where all the partners sat, or loudly announce “You did it!”

And in an industry where personal, artistic investment can fuel decision-making, he remained relatively even-keeled. “There’s no screaming, urgency, there’s no bloody consequences. We’re in it together,” recalls former team member Jennifer Kinon of the work culture he built.

Pentagram is structured in such a way that forces attrition, as designers there hit a growth ceiling unless they become a partner, which is rare. So when the time came to move on, the learned self-sufficiency of the Bierut team created a diaspora of independent design studios: Champions Design, Cobbco, Order, Cotton, Fay, and Franklyn are just a few founded by his former team members. Even in their own firms, several designers I spoke with said they ask themselves to this day, “What would Michael do?”

All this has made Bierut into a father figure in the design world. Both Order founder Jesse Reed and Fay recalled car rides home from meetings. “It felt like you’re with your dad,” says Reed. “He would play the Talking Heads and have his sunglasses on. He would start singing in the car.”

Bierut once described the Vignellis as “surrogate parents,” and though he shifted uncomfortably in his seat when I asked him about being thought of as a “design dad,” it’s that quality of trust, pressure, and generosity that helped build such a strong alumni network in a new generation of designers. It’s also similar to how Massimo and Lella’s son Luca Vignelli described Bierut’s relationship with his family: “He was like a second son for my father, and as a graphic designer more similarly spiritually attuned, so I guess that made him a sort of adopted brother to me.”

The client whisperer

Bierut’s alumni consider him to be an unflappable client whisperer. “I’ve seen him do presentations where he hadn’t seen the most recent version of the deck,” says Hamish Smyth, a former team member who now owns the design studio Order with Reed. “Sometimes in the beginning they were printed out on paper still, he’d flick through the papers for like, 30 seconds. ‘Okay, got it,’ and then just go in and crush the presentation. . . . You’ve got people sweating, preparing for these things for days, and he would just come in. He has this natural oratory ability.”

Smyth recalls a real estate client that came into the office several times to review their proposal on screen. They couldn’t get approval. So Bierut suggested going old-school. They printed dozens of logos on 12-by-12-inch sheets mounted on boards and wrapped in paper like Vignelli used to do. Bierut presented one-on-one with the CEO. And the horse and pony show worked. (Bierut, however, didn’t recall this.)

Bierut presents as familiar and approachable, sometimes code-switching based on the client, as Cobb recalls was the case in the casual tone he took to defuse tensions with the many native New Yorkers who were MTA stakeholders for their OMNY project. Reed recalls leaving meetings with a luxury real estate group “white in the face,” as they threw money at them to try to get the work on faster timelines. Bierut was unfazed. Reed recalls him saying, “Can’t we just do the thing that we signed up to do and get paid to do that and then deliver and have a good day?”

Verizon’s logo design was the easy part, according to Fay. “Everything that came after that was really challenging and really political,” he says. He recalled “really disproportionate” demanding timelines, in which “tons of employees” asked one or two people from Bierut’s team assigned to them to crank out work. “Michael was really great at setting boundaries with the client from the outset about what we’re going to deliver to you.”

He also had an unrehearsed approach to presenting. “He just treats people like people and that’s his best trait,” says Reed.

“He started to show you he had a form of generosity about another person’s point of view,” says Scher, who recalls him using baseball analogies with male clients, because that was a relatable form of communicating design decisions. “I’ve never once sat in with Michael on a meeting and thought, ‘he is blowing smoke up these people’s ass,’” says Cobb. (Bierut did, however, write an essay on the art of bullshit.)

But for all his generosity, Bierut does like to talk. He recalls coming out of a meeting with founding partner Colin Forbes when he’d just started at Pentagram. “He gently put his hand on my arm and said, ‘I’ve got one bit of advice for you.’ I leaned down and he said, ‘Don’t talk so much.’ I went completely red. I was horrified. I was so eager to please everyone that any bit of criticism just felt like an anvil on me. But he was right. The way I ended up shifting that was by saying you don’t learn anything by talking, you learn by listening.”

Bierut accepts that clients are people, and people are complex. Pushing your way through doesn’t solve for that. “They’re successful, so there’s something they’re really good at doing, but whatever they’re good at doing isn’t this, or else they wouldn’t have called for help,” he says. “It feels like all of a sudden they’ve abandoned the world of business and they’re somehow in the world of black magic, you know?”

He compares a slide deck to a Rorschach test. “They’re all ready to unload whatever their hopes, fears, dreams, nightmares are onto these shapes, colors, and forms you’re showing them.”

Ultimately, the key to working with clients is understanding how to deal with people, and that “there’s no one way to prevail,” says Bierut. “One of the reasons I love being a designer is that I love clients. I don’t have a love-hate relationship with clients. I often say even the clients that I hate, love me.”

People don’t vote for logos

It was 2014, and Bierut’s phone was ringing. This in and of itself wasn’t unusual. Bierut, then in his fifties, had already been a partner at Pentagram for nearly 25 years. The name carried notoriety. And so, calls were expected. But this circumstance in particular was a bit strange: It was Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. They needed a designer to craft the campaign’s identity. Would he help?

You’ve seen the final result as part of hundreds of millions of dollars of political advertising during her 2016 campaign: on yard signs, in digital ads, and at the end of swing state commercials. The design has gotten its fair share of criticism, but it’s also a good representation of Bierut’s approach. The concept is simple and clear, with a clever play on visual elements, like much of his work: a sans-serif capital H, comprising two vertical lines and a forward arrow. Hillary equals forward progress. (“A sort of design that I like to do is blunt and obvious,” he noted in 2016.)

The first time that Bierut met with Clinton, he recalls telling her that people “vote for candidates who they think can improve their lives. They don’t vote for logos.” Instead, it acts as a signature, according to Bierut. It gives “people a thing to coalesce around, mak[ing] sure that when your messages are going into a complicated, crowded environment, people can tell what you’re signing off on, and that they know it when they see it.”

The identity project, code-named “Hi-C,” was secretly developed with assistance from Reed and advice from Miller. His former team member, Kinon, was the campaign’s design director responsible for its distribution. The identity had an easily understandable concept and workhorse framework that made it adaptable and participatory. But its tight corporate style irked many people in the face of Trump’s bombastic approach to campaigning. Critics saw the arrow as inadvertently symbolizing a move toward the right, rather than forward as intended.

We all know how that turned out. After Trump’s win, the work led to both real backlash and reckoning about design’s efficacy, at a moment when conversations about the power of design were at an all-time high, and the industry pushed design as a secret weapon for solving deep-seated problems of all kinds and “design thinking” as good business. Critics saw the campaign branding as responsible for her loss. “Donald Trump’s graphics were easy to dismiss,” Bierut wrote in 2017. “They combined the design sensibility of the Home Shopping Network with the tone of a Nigerian scam email. Like so many other complacent Democrats, my only question was: Why is this even close?”

Of course, broader foundational political, cultural, and social issues also factored into the loss. Long-standing, foundational agreements of American politics were shifting, along with party coalitions. Insatiable grievance proved to be a winning idea. “Design can’t overcome people’s fears and prejudices,” says Scher. “It just can’t do that messaging. It can to a degree, but you find out that people live in their own communities and that the breakthrough can be very different unless you’re selling something universal, like soap.”

I asked what he’d say to those who felt the branding was responsible for Clinton’s loss. “Assuming those people are graphic designers, I would say for most of my life I’ve shared your exalted view of the power of graphic design to change the world,” he says. “I think it can change the world in many cases. I’m not sure this is a moment where the right logo or the wrong logo would have made a critical difference.”

If he feels guilty about one thing, he says, it’s using what was successful for Obama as a model. The introduction of a logo, designed by Shepard Fairey, was a first for political branding, and marked a clean corporate approach Bierut followed, based on one initial. “I never made that case explicitly, but I think in the background that was sort of a set of expectations that I didn’t question clearly enough.”

But Bierut is used to criticism, and seems to consider it part and parcel of working in the public sphere. “There are people that think it sucks, but in what we do, some things become famous, some become infamous,” he says. “You can just do the best you can do.”

For as outwardly self-deprecating and humble as Bierut is, since early in his career he’d pined for the design industry to get the same attention as other cultural pillars like movies. He considers his push to make graphic design part of the general zeitgeist his most significant impact on the industry, work he’s largely done as a writer, speaker, and industry advocate completely outside his role at Pentagram.

“All along, even when people were criticizing things that I had done—and I got a lot of criticism for things I’ve done over the years—I remember thinking, I asked for this. I was dying for people to notice that I had done a logo for a presidential campaign or changed the logo of a big telecom company or changed or updated the logo of an online workplace communications platform,” he says referring to Verizon and Slack, which he developed after the Clinton logo. “Now two-thirds of them seem to hate it, maybe even more,” he says. “But that was what I wanted. I wanted people to notice it and so people were talking about it.”

A new role to play

I met Bierut again on a Tuesday afternoon in April in Pentagram’s most recent office on Park Avenue. The office was full of young designers sitting at Apple desktops, quietly clicking away, and milling around between meetings. The firm’s newest partner, Andrea Trabucco-Campos, met with designers in Bierut’s former conference room. Partner Matt Wiley was in conversation with another partner, bent over papers splayed across a conference table in another room. Bierut has a small built-in desk next to partner Michael Gericke’s, by a built-in bookshelf filled with books from his collection over the decades, including a designer encyclopedia his wife Dorothy gifted him in the ’70s. He’d given up his larger desk when he became part-time. Aside from Luke Hyman, the other partner desks were empty, but there was energy in the air.

As we made our way around work stations, Bierut introduced me to partners and stopped to sit next to a designer who was formerly on his team, and was working on an identity he’d passed to Trabucco-Campos. He loved the work she was doing and wanted me to see it, so we sat down at her monitor and she walked us through the concept. Bierut gushed. And even though he said the partners had gotten more deliberate about what he took on since November to keep him part-time, as we moved through the office, colleagues constantly stopped him, shouted for him, and consulted with him.

Aging creates an interesting tension because it involves both constancy and change. For Bierut, aging has shifted the way other people perceive him over time. “First you’re like a kid in the room who no one’s expecting to talk,” Bierut says. “Then there’s a moment where someone like Massimo Vignelli turns to you and says, ‘Michael, why don’t you explain the idea behind this one?’” Then, you become the same age as your clients and you take big swings, then a steady, big brother figure, and then, in a “horrifying moment,” you remind your team of their dad, he says. And you have to find a new role to play.

But Bierut’s sense of self has been consistent. He recalls noticing how he’d aged on video calls during the pandemic. “It’s funny because in your head you’re the same person, you haven’t changed,” he says. “I feel like I’m exactly the same person I was the first day I sat down to work at Vignelli Associates in 1980.” He’s still essentially driven by the same motivations as when he dropped coins in a payphone 40 years ago.

As Bierut wandered the office floor, he had a conversation across the room about building architecture related to a project he was helping with. Someone stopped him to show off a magnetic lip gloss case design in development. He pushed back a meeting due to our interview. In some sense, upon retirement, it seems his team just got a whole lot bigger.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0