The ‘Daniel Tiger’ effect: How quality kids’ TV impacts teen mental health—and why cuts to PBS could be disastrous

Parents used to be freaked out when kids were reading romance novels or Horatio Alger books. It seems quaint now, when so many parents (and teens!) are concerned about the effects of social media and screen time. But it speaks to a universal truth: The stories we learn have the power to shape our lives.

Stories are among the oldest forms of teaching. They don’t just shape our thinking, they actually affect us at a neural level. This is especially true for kids: The entertainment that children consume during their most formative years plays an important role in shaping who they become and how they relate to the world around them.

Now, however, some of the most reliable sources for high-quality children’s media are on the chopping block with the administration’s threat to cut federal funding of PBS, accounting for 15% of its funding, which will only limit access to valuable programming that can impact future generations. In fact, the U.S. Department of Education recently notified the Corporation for Public Broadcasting about the immediate termination of its Ready to Learn grant, taking away the remaining $23 million of a grant that was set to end on September 30. PBS has received this grant every five years for the past 30 years, and it accounts for one-third of PBS Kids’ annual budget.

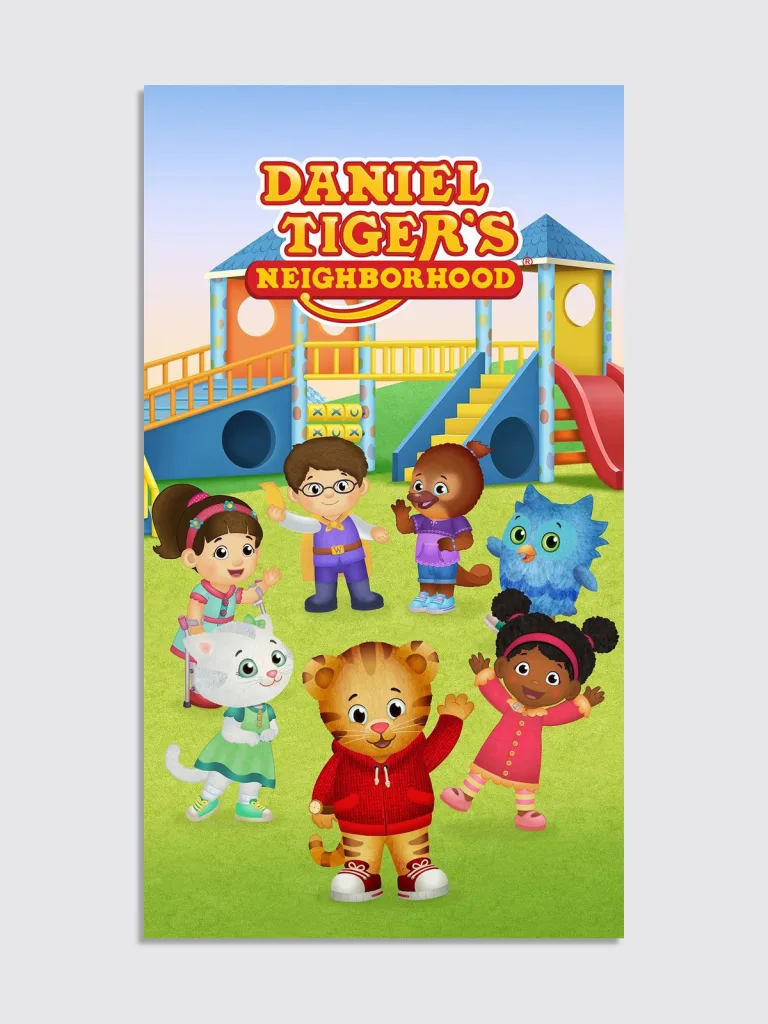

There have been many studies on the immediate effects of media on children, from specific learning goals to impacts on self-esteem. But one thing that hadn’t been measured extensively was how much those learnings persist over time. That’s why my colleagues and I at the Center for Scholars & Storytellers at the University of California, Los Angeles, studied the long-term impact of Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood, a modern-day Mister Rogers-inspired program. The show, which we weren’t involved with, was developed in close collaboration with child-development experts to purposefully and thoughtfully model social skills and emotional regulation tools for young kids.

To see how much teens had learned from watching Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood as younger children, we conducted a mixed-methods study surveying 150 teenagers across the United States. The results were striking: 57% remembered learning strategies from the show, like understanding and managing emotions, academic success, and behavioral regulation. And one in five told us they still use those techniques (like deep breathing and other calming strategies) when they’re upset today.

Interestingly, the teens in our study didn’t just recall facts or songs. They also remembered feelings of safety and warmth. Many associated watching the show with solace during difficult moments in early childhood. We know that storytelling can provide frameworks for coping during times of uncertainty. And in fact, this kind of comfort is increasingly important to kids today: In our research, we found that young people ages 10 to 24 now rank safety as a higher priority than having fun.

Media can be a powerful way to support kids’ mental health: One study found that a popular hip-hop song featuring a story that has a man calling the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline led to increased calls to that hotline and a reduction in suicides.

But given our nation’s ongoing youth mental health challenges, we can’t leave this to chance: Storytelling grounded in research—designed to meet children where they are emotionally, cognitively, and socially—is more needed than ever. These kinds of stories can act as a form of early intervention, providing children with tools that can support their psychological well-being for years to come.

When Fred Rogers testified in front of Congress back in 1969, he said, “If we in public television can only make it clear that feelings are mentionable and manageable, we will have done a great service for mental health.” Our study of Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood provides concrete evidence supporting his prescient statement, showing how quality children’s programming can indeed make feelings mentionable and manageable, thereby serving mental health.

Nearly 60 years later, public television continues to be a haven for thoughtfully produced programs that have a research-backed positive impact on kids. PBS Kids is one of the rare organizations that intentionally creates media in deep collaboration with researchers who study child development.

Another study we published found that movies featuring more character virtues like gratitude or empathy make more money at the box office. This is a real opportunity for the rest of the media industry—public media has shown us where the bar should be: If we give young people stories that honor their feelings, and help them navigate an increasingly complex world, the positive impact will last for years to come.

We’re not going back to the days of romance novels and Horatio Alger for teens: Screens are here to stay. But the real question is: What kinds of content are we putting on them? The majority of the media industry is motivated by profit, which means putting kids first is not always the objective. This is exactly the reason we need to continue to fund public media. Because when we prioritize and fund thoughtful, research-based content that meets kids where they are—and shows them where they can go—we’re not just creating better programming. We’re building the foundations for better mental health, a stronger society, and a healthier democracy.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0