The real meaning behind that viral Department of Homeland Security painting

In recent months, The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has used its social media platforms to promote its vision of an ideal country. In between posts celebrating mass deportations and defending ICE, the department has taken on the role of curator, posting a series of artworks that appear to communicate an idealized, Eurocentric concept of the American dream. The department’s artistic choices haven’t been subtle, but none can compare to the overt messaging of its most recent art choice.

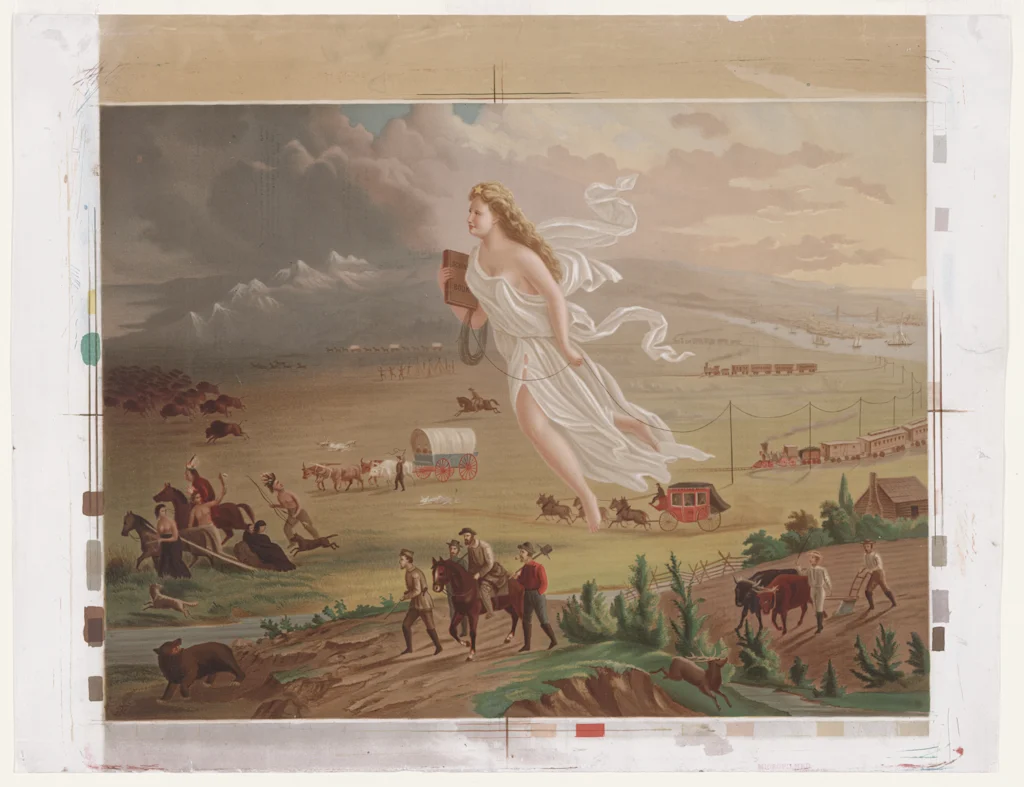

On July 23, DHS posted a painting titled American Progress, alongside the caption, “A Heritage to be proud of, a Homeland worth Defending.” The 1873 painting by John Gast shows a group of white pioneers traveling west, forcing a group of Indigenous people out of frame.

The irony of the DHS’ post and caption, according to Martha Sandweiss, Princeton professor and historian of the U.S., is that American Progress does not show Americans “defending” a homeland: “What we actually see here are American settlers invading a homeland,” Sandweiss says. “Of course, that’s the homeland of the Native people that we see fleeing into the darkness, and, metaphorically, into extinction.”

Gast’s painting has long been used as an embodiment of the concept of “Manifest Destiny,” a belief held by many during the nineteenth century (and beyond) that the United States was destined by divine right to control the entire territory from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. For decades, this dogma was used to explain and legitimize the forced displacement and ethnic cleansing of Native Americans.

The DHS’s choice to highlight American Progress shows that its art choices have become an intentionally provocative flashpoint in an ideologically divided United States. And, Sandweiss says, it represents a whitewashing of the past that might signal a desire to exclude non-white Americans in the present.

The fraught history of John Gast’s ‘American Progress’

Gast’s work on American Progress began in 1872, when he was commissioned to make a work for George Crofutt, an American publisher of several different guides promoting westward expansion.

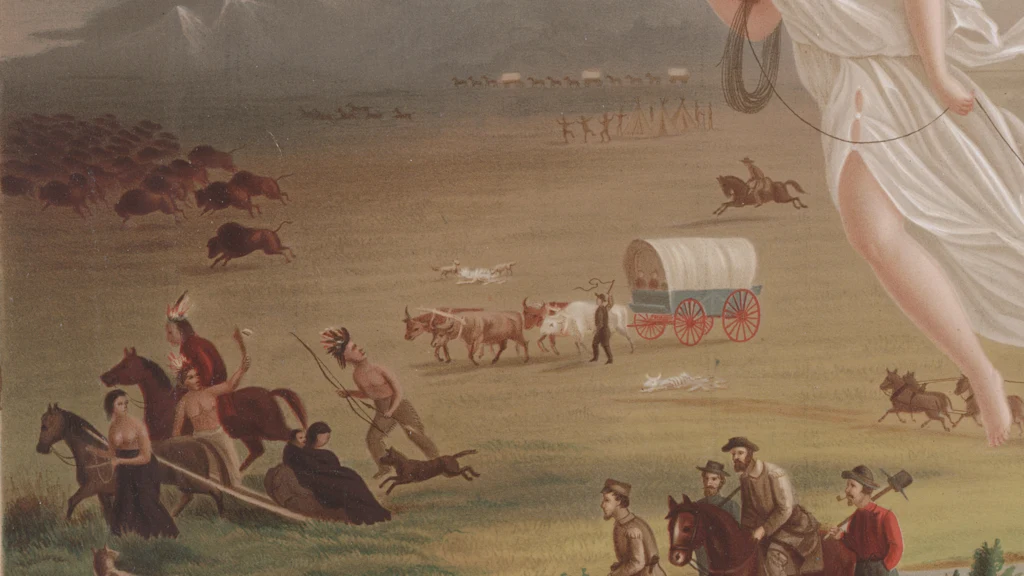

The image shows settlers traveling by stagecoach, conestoga wagon, and railroads, guided by a giant allegorical female figure of America, who holds a schoolbook in one hand and places a telegraph wire in the other. While these figures are glowing in a bright light, the fleeing Indigenous people are shrouded in darkness.

“On the one hand, [Crofutt] needs a set of ideas that his readers will readily respond to and are, in a sense, already familiar with,” Sandweiss says. “In addition, he’s using the picture as a kind of propaganda. He’s picturing an imaginary scene that he hopes will resonate with people who might want to buy his travel guides and travel west themselves.”

American Progress ultimately appeared in the monthly publication Crofutt’s Western World. The image’s description, as written by Crofutt, is full of racist tropes that align with the Manifest Destiny ideal of bringing “civilization” to an “uncivilized” place and people.

![A image of a vintage printed advertisement with text on it. Which reads as follows:

AMERICAN PROGRESS! Subject: The United States of America.

This rich and wonderful country - the progress of which at the present time, is the wonder of the old world - was, until recently, inhabited exclusively by the lunking savage [or lurking, print is smudged] and wild beasts of prey. If the rapid progress of the](https://images.fastcompany.com/image/upload/f_webp,q_auto,c_fit/wp-cms-2/2025/08/i-3-91378813-dhs-painting.jpg)

“This rich and wonderful country—the progress of which at the present time, is the wonder of the old world—was, until recently, inhabited exclusively by the [lurking] savage and wild beasts of prey,” Crofutt writes.

Crofutt goes on to describe how the painting associates American settlers with the transformative power of technology, like transcontinental rail lines, trans-Atlantic trade (pictured in the top right of the image), and new telegraph wires. On her head, the symbolic female figure of America wears what Crofutt calls the “Star of Empire.”

In contrast, he writes, the lefthand side of the image “declares darkness, waste and confusion.” The Indigenous people in the image are visually grouped with fleeing wild animals like a herd of bison and a black bear, all shown, per Crofutt, “as they flee from the presence of the wondrous vision.”

“It doesn’t reflect reality in any way”

According to Sandweiss, it’s no coincidence that American Progress shows trains in conjunction with the displacement of Native peoples. By 1872, it had been three years since the completion of the first transcontinental rail line, and several other lines were already underway. In the coming decades, Indigenous people would be forcibly located away from these routes.

“Absolutely, when the large reservations were created in the late 1860s, it was in part to move Native peoples away from the prospective railway lines so that they would not pose a threat to either the railroad companies or the settlers that the railroads would bring west,” Sandweiss explains.

American Progress, Sandweiss says, is an idealized version of the American settler story. Encoded in the image is the idea that white Europeans were the sole people living in the American West, while, in actuality, the region was primarily settled by people of Spanish origin who arrived from Mexico.

“It doesn’t reflect reality in any way,” she says. “It doesn’t reflect the multiple sources from which non-Native people came into the West. It doesn’t depict the more complex racial identity of people who came into the West, which, by 1872 is including more free people, is including people coming north from Mexico, and it doesn’t convey the role of women and families in the settlement of the Western landscape.”

The press office of California Governor Gavin Newsom also reposted the painting with the response, “This painting is housed at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles. The museum heavily features Native American history and intentionally embraces a more honest, inclusive understanding of Western history—a concept the Trump administration fails to understand.”

Whitewashing of the past leads to whitewashing of the present

Many American schoolchildren will be familiar with American Progress because, for decades, textbooks have used it as a visual explanation of the Manifest Destiny concept. The image’s themes of divine conquering, the spread of technology, the superiority of European settlers, and patriarchal structure capture the complex dynamics at play within this belief system.

For the DHS to post this painting through an uncritical lens, Sandweiss says, signals “a broader ignorance of American history on the part of the current administration”; an ignorance that she sees reflected in the administration’s efforts to alter the historical information shared by agencies like the Smithsonian and the National Park Service.

“If you overly simplify the past—if you pretend that the only important people in the story were white men—you not only distort the past and dishonor the many other kinds of people who were part of American society at that moment, you also suggest that there’s not a space for different kinds of people in the present,” Sandweiss says. “Whitewashing the past makes it easier to whitewash the present, and pretend that people who are not like the people we see in this painting have never had a part in the American nation.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0