Why AI has a big branding problem

If artificial intelligence is going to take over the world, it may need a rebrand. Not only do many of the company logos look like swirling vortexes, but because no one has the patience for its name, a mouthful of eight syllables, we have fallen back on the now-ubiquitous initialism: AI. Those two letters have been on everyone’s lips for the last several years, but they don’t exactly roll off the tongue. Try saying them without sounding like an awkward amalgam of Fonzie (“Ayyyy!”) and Bart Simpson (“Ay, caramba!”).

Vowels in English just don’t play well together; string too many of them in a row and you soon sound like Old MacDonald having a farm. Sorry, EU, UAE, and IEEE, but abbreviations need some meaty consonants thrown in to give them some heft, à la “U-S-A!” Sam Altman and Jony Ive may learn this the hard way should their newest venture in AI (i.e., io) end up evoking the Lone Ranger (“Hi Yo, Silver!”) or Ed McMahon (“Hiyo!”).

AI’s written form has issues as well. Like many such constructions, AI initially had periods after both letters to hammer home its status as an abbreviation. Those periods were firmly in place in the title of Steven Spielberg’s 2001 A.I. Artificial Intelligence, which went with a belt-and-suspenders naming approach to really make sure that the audience knew what the movie was about.

To this day, some stodgier publications like The New York Times and The New Yorker still insist on the “A.I.” formulation in their house styles (the latter, as a matter of fact, only just stopped writing “Web site” this year!). But the rest of the world has dropped the periods in favor of the sleeker “AI” convention. In this decade, for instance, over 5,000 U.S. trademark applications have contained “AI” while only 76 specified “A.I.”

A problem, though, occurs when the period-less “AI” is expressed with the use of a similarly-hip sans serif typeface. Without those helpful serifs, “AI” is, to the human eye, indistinguishable from “Al”—as in Al Pacino. (Eerily and fittingly, though, computers can tell the difference.)

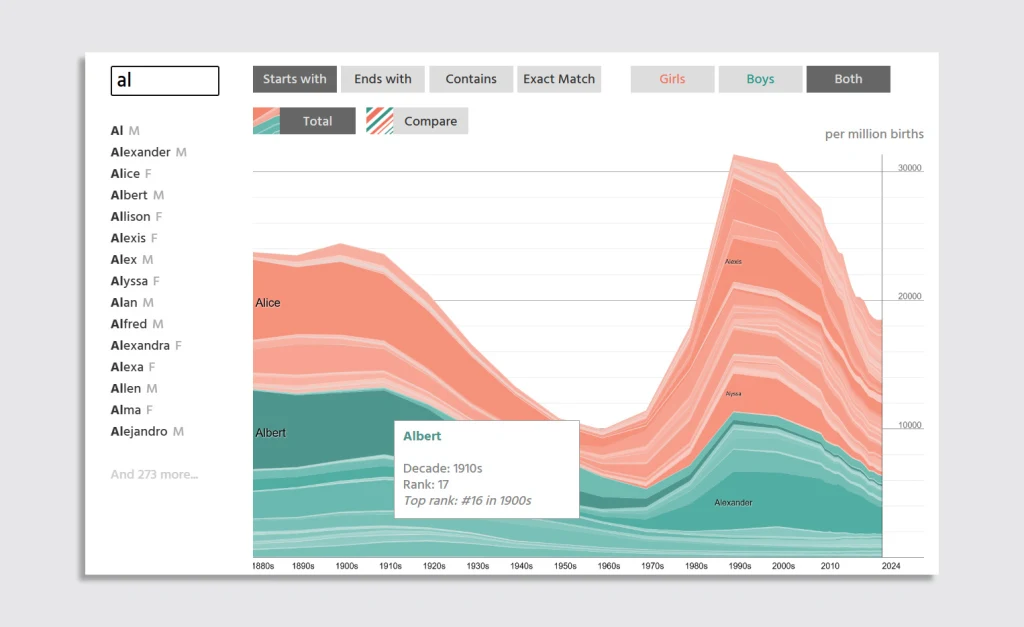

An analysis of U.S. baby name data reveals that names starting with “Al” peaked in use in the 1990s, meaning that there are many thousands of thirtysomething Americans who live in fear that writing their nickname “Al” on one of those “Hello my name is” stickers will inspire confusion, or worse, mockery, from a younger Gen Z coworker. Paul Simon wouldn’t have a chance with “You Can Call Me Al” today.

NBC Sports made lemonade from the lemons of this “AI/Al” confusion at last year’s Paris Olympics, delivering custom highlights narrated by an AI version of sportscaster Al Michaels. But the difficulties don’t end with the Alans and Alberts of the world. Consider that the definite article—the “the”—of Arabic, the world’s fifth-most-spoken language, is “Al” and you start to grasp the full extent of the situation.

One might think that a solution might lie with the British tendency to express acronyms and abbreviations with an initial capital rather than all-caps (“Nato” rather than “NATO”). But using “Ai” just opens new cans of worms ranging from Ai Weiwei to Adobe Illustrator. And that’s even before taking into account the recent propensity of high-ranking government officials to mistake artificial intelligence for A.1. Steak Sauce.

Sadly, following the mid-twentieth century origin of the term “artificial intelligence,” no clever Madison Avenue ad man came up with a catchy nickname like, say, “artelligence,” and so we’re stuck for now with “AI.” If various tech pundits are to be believed, we have just a few years before the arrival of artificial general intelligence (AGI). But in that time perhaps the world’s best and brightest branding and marketing minds could be assembled in a sort of modern-day Manhattan Project to come up with a replacement for the term “AI” with which to welcome our new robot overlords.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0