How the world’s busiest airports are future-proofing themselves without missing a beat

The clock has just struck midnight, and about 60 people are bustling around an empty taxiway at Dallas Fort-Worth International Airport (DFW). Architects, contractors, engineers, ground crew—everyone has gathered for an unprecedented event. After years of planning and months of meticulous scheduling, six massive buildings are about to be wheeled into place near Terminal C. Yes, wheeled.

DFW is the fourth-busiest airport in the world, and it’s currently undergoing a $9 billion project that includes an expansion of Terminals A and C, as well as a new Terminal F. To build out the airport without closing any gates or disrupting the flight schedule, HOK, the lead architecture firm behind the project, turned to an increasingly popular method of building: modular construction.

Modular construction has long been a solution for schools and apartment complexes, but airports in cities such as Dallas; Los Angeles; Portland, Oregon; and Atlanta are now embracing it as a solution to quickly expand their square footage as a tourism boom pushes airports to their limit.

“Airports have high operational cost, and that is what modular construction offsets,” says Richard Saunders, engineering practice leader for HOK’s Atlanta studio. He estimates that the operational impacts are roughly cut in half.

Designing for the future of tourism

When the HOK-designed Dallas-Fort Worth airport opened in 1974, it was hailed as a modern marvel of airport architecture. HOK’s director of engineering, Matt Breidenthal, says it even graced the cover of Life magazine that year. The original design, however, “wasn’t built for modern air travel,” he says.

Over the past 50 years, global tourism has surged drastically, jumping from 680 million tourists in 2000 to 1.4 billion in 2024. After a yearslong, pandemic-induced slump, the travel industry is expected to reach a new record high in 2025.

DFW is responding to this demand by adding 115,000 square feet and four gates to Terminal C, plus 140,000 square feet and five gates to Terminal A. An all-new Terminal F, designed by HarrisonKornberg Architects and Luis Vidal + Architects (slated to open in 2027), will have 31 new gates. The Terminal C and A expansions are scheduled to be completed by the end of this year.

A decade ago, a major airport expansion project would have required closing runways, as traditional stick-built construction required erecting buildings directly on-site and turning operational gates into construction zones. But HOK suggested fabricating the structures at a nearby greenfield location, then transporting them into place overnight, during low-traffic hours.

DFW was one of the first major airports to pioneer modular construction for terminal expansions back in 2022, when six prefabricated modules formed part of a new 80,000-square-foot concourse at Terminal C. The largest module then weighed 550 tons. This May, the airport set a new record, wheeling in modules twice as heavy.

For HOK, modular construction fits large-scale airports perfectly because it can offset steep operational costs. The architects also see potential in stadium renovations—especially American football arenas, which have a limited amount of time to complete renovations in the off-season.

Whatever the building type, says Saunders, “it has to be the right size to make it worthwhile. If the building is 10,000 square feet, it doesn’t make sense to build here then move it over there, because there’s a cost to moving it.”

Moving a 1,200-ton building

At DFW, each move took place over six nights, spaced two nights apart to allow for contingencies. Each operation began around 9 p.m. and wrapped up by 3 or 4 a.m., just as runways reopened to daytime flights. HOK built the new modules just outside the airport’s security perimeter, which helped accelerate construction and inspection processes.

Moving a 1,200-ton building across a taxiway was made possible by Mammoet, a specialist in heavy transport. In 1985, Mammoet invented the self-propelled modular transporter (SPMT), a platform on wheels that can carry enormous loads by driving underneath heavy modules, then lifting them using hydraulics.

A spokesperson from Mammoet explained that while SPMTs aren’t new, the combination with its “Mega Jack” system is a recent innovation. The technology, which was first introduced in Atlanta, allows heavy modules to be lifted to nearly any height and directly onto foundations—rather than just a few feet off the ground. The DFW operation required an “army” of SPMTs, all coordinated by a single operator using a sophisticated remote control system that Brendeinthal jokingly called a “glorified Game Boy.”

Once wheeled into position, the modules were “parked” adjacent to the terminal, where a precise operation aligned them perfectly before lowering them onto pre-built foundations. After all modules were in place, the team completed the structure by “stitching” them together with concrete.

The airport now faces the final tasks: installing baggage handling systems, mechanical units, and interior furnishings.

Future-proofing airports

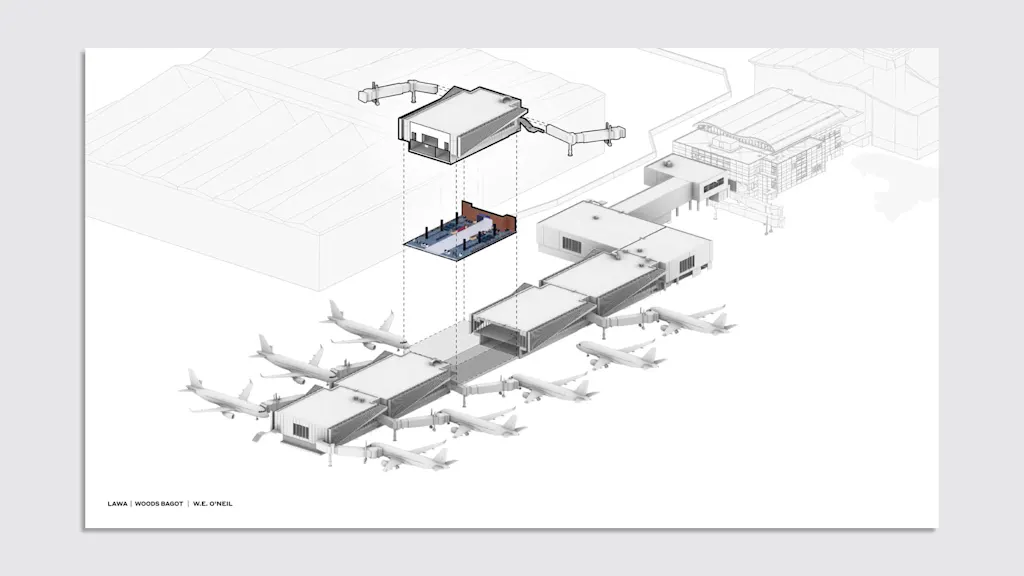

At DWF, speed and operational efficiency were key, but modular construction can also prove more sustainable. When architecture firm Woods Bagot started working on the new American Airlines terminal at Los Angeles International Airport, the goal was to prove that major public infrastructure could be delivered faster, and smarter. This meant designing a fully demountable terminal.

The construction industry is responsible for approximately 39% of the world‘s global greenhouse gas emissions, and more than a fourth of those come from embodied carbon emissions associated with the production of building materials and construction. If LAX ever needs to reconfigure its layout, it wouldn’t need to demolish this terminal and build a new one from scratch. Instead, it could be relocated and repurposed as office space or community facilities.

The LAX expansion involves the MSC South Concourse—an eight-gate, two-story building. Woods Bagot used a system called off-site construction and relocation (OCR), which is akin to modular construction but with greater scope. Unlike at DFW, where windows and finishes were added post-installation, the LAX team built nearly the entire terminal off-site, including windows and mechanical systems. Only final finishes like terrazzo floors and wayfinding signs were installed on-site.

This made some of the modules heavier than they would have been, but Matt Ducharme, Woods Bagot’s West Coast design leader, says the up-front investment helped avoid the kind of disruption that installing a gigantic windowpane would have caused. “LAX is a 24/7 airport and none of the takeoffs or arrivals were disrupted at all,” he says. The architects’ calculations showed that OCR helped cut construction time by six months and saved approximately $30 million compared to a traditional stick build.

This technique also called for a rigorous design discipline, where every element had to be justified. “One of the more joyful aspects of the project is the brise-soleil,” Ducharme says. The shading feature blocks heat from the glass facade, actively cooling the building, but if it had been an architectural flourish, it wouldn’t have made the cut. As Ducharme puts it: “Every piece of the building needs to be very hardworking.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0