Step inside the Nakagin Capsule Tower, one of the world’s weirdest architectural wonders

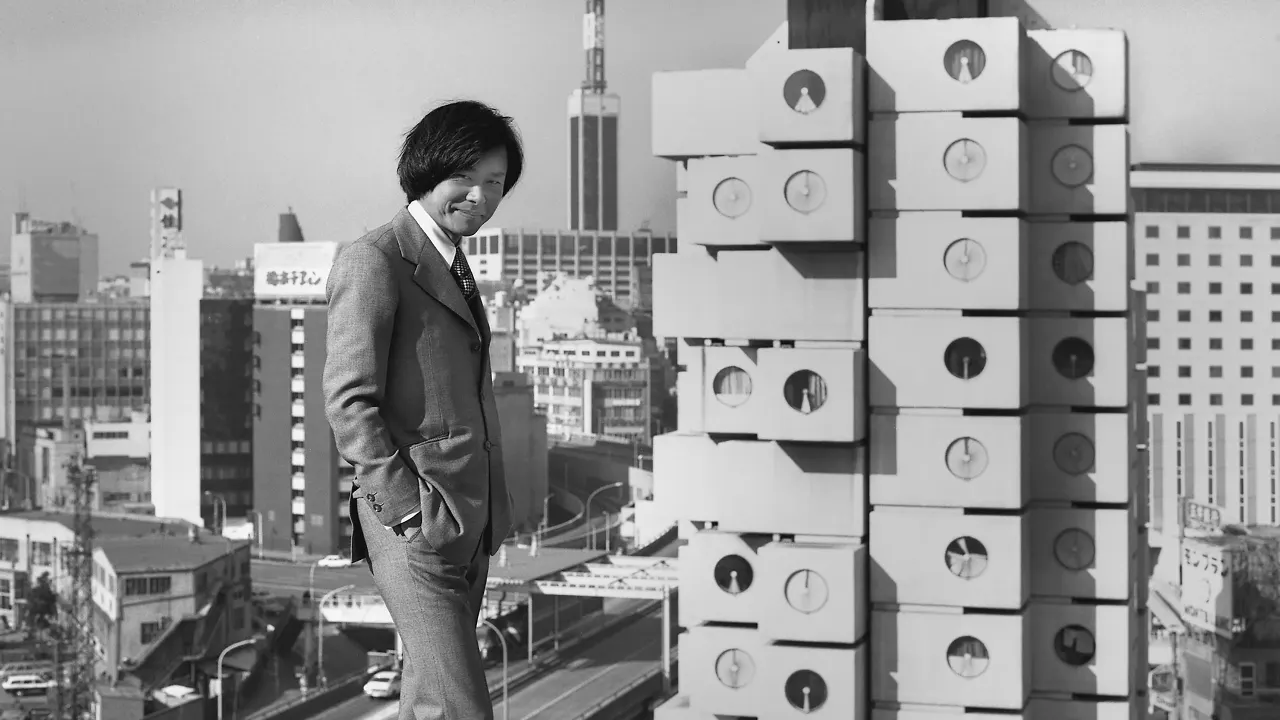

The Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo was one of the most distinctive buildings of the 20th century, both for its oddball form and for its tumultuous evolution. A space station stack of 140 prefabricated cabin-like capsule living spaces completed in 1972, the building went from high concept design to marketing triumph to architectural wonder to lamented demolition. Now, the building is taking on a new form inside the galleries of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) for The Many Lives of the Nakagin Capsule Tower, a year-long exhibition opening July 10. The central piece of the exhibition is the roughly 100-square-foot capsule A1305, a complete and fully restored living chamber from the building that visitors will be able to step inside.

“Especially for architecture exhibitions, sometimes we’re able to show actual pieces of buildings, or fragments,” says curator Evangelos Kotsioris. “But what is extremely rare here is that it’s a whole unit by itself.”

That’s because the building had a wholly innovative design: two tower cores surrounded with individual rectangular living units, or capsules, that attached to the structure like appendages. Designed for the Nakagin Company by architect Kisho Kurokawa, the building came to epitomize the avant-garde Metabolist movement that developed in 1960s Japan as an effort to use adaptable architecture as an avenue for rebuilding postwar Japan and Japanese society. In the mind of Kurokawa, who died in 2007, the capsule tower was meant to evolve, with old capsules being swapped out for new ones as needs and times changed.

This never happened, not exactly anyway. The building slowly decayed over the years and deferred maintenance doomed much of it to becoming uninhabitable before it was demolished in 2022. Some capsules and building parts were salvaged, though, and more than a dozen capsules have been fully restored. Capsule A1305 was acquired by MoMA in 2023.

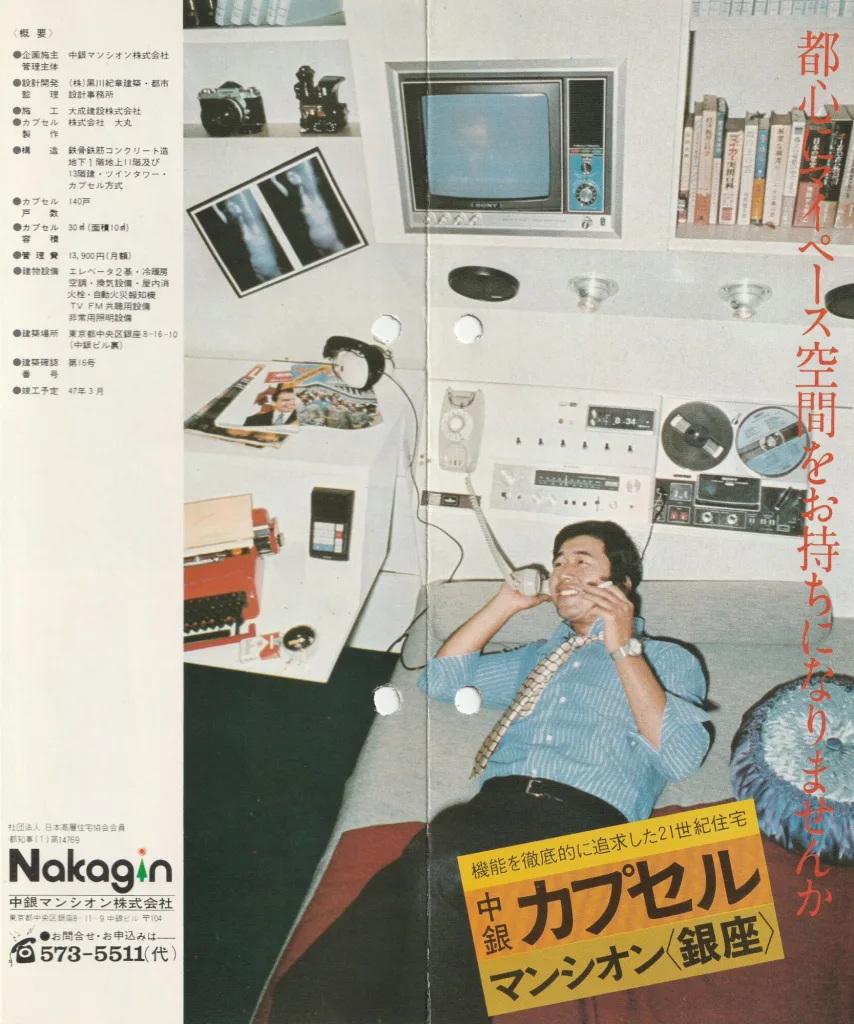

But the Nakagin Capsule Tower exhibition is more than just a showcase of an architectural curio. It features 45 other objects relating to the building and its design, including the only surviving physical model from the early 1970s, the original architectural drawings of the building, historic marketing material from the Nakagin Company for the building’s original use as a businessman’s pied-à-terre, and a digital building walk-through created with 3D scanning technology just days before the building’s demolition. Kotsioris also interviewed the group of residents who lived in the capsule tower during its final decade, and the exhibition includes documentation on the varied ways they repurposed the capsules.

“The capsule itself, if you just look at it from the outside, it’s not telling you much. You cannot fully comprehend the radicality of the proposition behind it,” Kotsioris says. “I thought it was really important for its first presentation in New York to contextualize it properly, with the ideas about the birth of the project, the drawing, the models, but also interviews with residents.”

The capsule in the exhibition is a faithful recreation of the way the building was originally marketed, as a part-time residence for businessmen visiting Tokyo for work. One famous ad for the building shows a smiling businessman inside a capsule, seemingly after work, lounging on the bed while talking on the phone and smoking a Marlboro, with the capsule’s built-in Sony TV and audio electronics playing in the background.

Kurokawa intended the building to be more than just a space for businessmen, envisioning the building with multiple capsule sizes for offices, hotel rooms, and family residences. That vision narrowed, but also evolved, as Kurokawa later went on to design the first capsule hotel in Osaka in 1979.

Even short of Kurokawa’s original intent, the Nakagin Capsule Tower has influenced generations of architects, while also pushing new ideas about urban living in Japan, impermanence in the built environment, and prefabricated housing. “Even though there was a lot of speculative projects about capsule living and prefabricated dwellings, even from the early 20th century,” Kotsioris says, “this was really the first realized prototype on the ground that said this is an idea that you can actually put into action.”

MoMA members will be able to step inside the capsule during several special events throughout the exhibition’s run, which Kotsioris says should be a treat. “I remember the first time I entered a capsule,” he says. “There’s something extremely magical about being inside it, because it’s very small, but at the same time it feels spacious.”

The Nakagin Capsule Tower exhibition explores the ways the building played multiple roles in its five-decade lifespan. Despite the compact size of the capsules, they evolved over time from a kind of temporary living quarters to more of a permanent residence. And, Kotsioris found, the individualist nature of the capsules changed over time, too, as maintenance and structural issues began to plague the building. “The more the building started to break down over the years, the more it generated social interactions,” he says.

Residents told him that frequent earthquake evacuation alarms in the aging structure turned into social gatherings in the lobby. When the hot water boiler stopped working, a group of residents would travel together to a nearby bathhouse to take showers, and when the air conditioning broke, they’d gather in one of the units with a working dehumidifier for drinks after work.

These unintended uses of the building—a version of the Metabolist architecture idea Kurokawa was designing around—helped it remain useful up until the end. “Kurokawa had one idea of how this project could be metabolized or change over time,” Kotsioris says. “And it did metabolize, but maybe in a different way than he would ever have imagined.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0