These geeks are building an early warning system for disappearing government data

To a certain brand of policy wonk, January 31, 2025, is a day that will live in infamy.

It had been nearly two weeks since President Donald Trump took office for the second time—days that passed in a swirl of executive orders to cut federal spending and rid the government of now-forbidden ideas—when suddenly, vast troves of government data began to disappear in a single day.

“My inbox exploded, and it was just people emailing saying, ‘Hey, do you know where this dataset went?’” says Meeta Anand, senior director of census and data equity at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

By The New York Times’s count, more than 8,000 web pages housing information on topics like vaccines, hate crimes, Alzheimer’s disease, and environmental policy simply went poof in a matter of hours. While most of those websites quickly came back online, there was no telling whether or how they had changed while they were dark.

This was the moment Chris Dick and Denice Ross had been fearing—and the one they’d been preparing for.

After the November 2024 election, Ross (who was, until January of this year, President Biden’s chief data scientist) began thinking about how to protect the data that underpins policies Trump was promising to undo. She reached out to Dick, previously an Obama-era Census Bureau official, to come up with a plan. “When I’m worried about data, Chris is the person I call,” Ross, who is now a senior fellow at the Federation of American Scientists, says.

For years, experts feared that a president known for pushing “alternative facts” would try to alter or erase fundamental knowledge. When Trump first took office in 2017, researchers raced to archive climate data and other government resources that looked vulnerable. After the 2024 election, archivists sprung into action once more, with a group called Data Rescue Project becoming a clearinghouse for the many simultaneous efforts to preserve government information.

That was vital, but in many ways Ross and Dick saw it as a first step. What the country needed wasn’t just a snapshot of data from January 2025, but a way to keep that data flowing—and a way to know what data might soon be at risk.

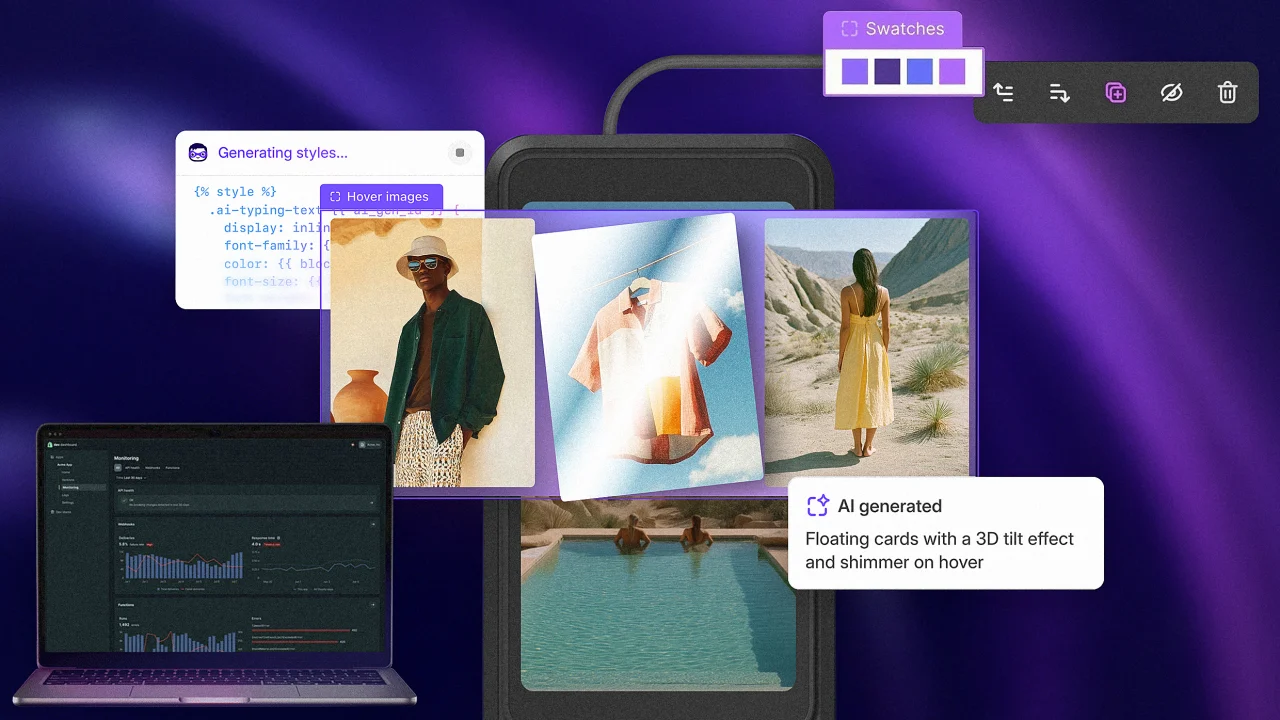

The result of their collaboration is a new project called America’s Data Index, which Dick describes as a sort of weather forecast for government datasets. Using a combination of automation and human review, the site is tracking roughly two dozen widely used datasets—from the National Crime Victimization Survey to the Census of Agriculture—to identify in real time any changes that are being made to the websites that host them.

“There are more changes to the federal statistical system and the federal government overall than we have seen at least in my lifetime,” says Dick, who now runs his own data firm, Demographic Analytics Advisors. Keeping tabs on how these changes are impacting people is “more important now than it ever has been,” he says.

The White House did not respond to Fast Company’s request for comment.

The Data Index also monitors other signs that data might be at risk of disappearing. Federal law, for instance, requires agencies collecting data on people to seek new approval every three years. The Index monitors which datasets are set to expire and whether the White House has moved to renew them.

Another signal of potential change comes in the form of legal requests the White House must submit each time it wants to change how data about people is collected. In some cases, the public has a chance to comment on those changes, known as Information Collection Requests; in others, where those changes are deemed minor, it doesn’t.

The goal, Dick says, is to alert anyone who might rely on that data—be it legal advocates, healthcare systems, journalists, or businesses—so they can respond before a crisis hits. “Weather forecasts are useful both in blue skies as well as in storms,” Dick says, “but they’re more useful before storms.”

To come up with an initial list of datasets worth monitoring, Dick and Ross worked with groups like the Leadership Conference to find out what data civil rights leaders were most concerned about losing. Anand says she viewed the Data Index as, in some ways, even more critical than an archive. “It’s one thing to preserve the data that’s already been collected, but you can’t manufacture data that was never collected at all,” she tells Fast Company.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the vast majority of change requests have related to executive orders the president has signed—most notably a January 20 order that, among other things, instructed government agencies to remove all statements, forms, and other internal and external messages “that promote or otherwise inculcate gender ideology.” As public reporting has shown, that order and others triggered a widespread purge across the federal government of terms like gender ideology, nonbinary, transgender, and more than 100 other words and phrases. But the change requests reveal exactly where and how that censorship is being carried out.

In just a three-week period in May, for example, the White House Office of Management and Budget submitted 62 change requests related to the gender executive order. Those changes include, for instance, removing a question from a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey asking young people if they’re transgender. Another request proposed altering questions about gender identity and hate crimes in the National Crime Victimization Survey.

In many cases, these changes were submitted as “non-substantive,” which means they can slide under the radar, without allowing for public comment. Yet these changes stand to wildly distort what we know about the country, by, say, pretending entire populations of people simply don’t exist. “People’s lived experiences need to be reflected in the data so that we are able to have a democracy responsive to people’s needs,” Anand says.

It can be difficult, of course, to get anyone worked up about protecting data at a time when so many other rights and institutions are being toppled. “Who’s going to march in the streets to save NOAA’s [the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] vegetation health index data?” Ross says.

But part of what Dick and Ross are trying to do is help a wider circle of people, beyond their fellow data nerds, understand how their lives are impacted by government data. As part of this project, they’ve launched another site, called America’s Essential Data, which is collecting individual stories of heroic uses of data.

Already, they’ve amassed accounts of government data being used to deliver tornado warnings in languages that local refugee communities can understand, businesses designing new products based on demographic data, and, yes, farmers using NOAA’s vegetation health index data to seek out tax relief during droughts.

Dick and Ross may not be able to stop the Trump administration from dismantling government data, but they can at least help us see the damage more clearly.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0