This new front-of-package nutrition label is designed to make us healthier

For more than a century, the U.S. government has tried to bring more transparency to food labels. It started in 1906, when the Pure Food and Drug Act cracked down on mislabeled ingredients and false health claims. Since then, regulators have required more disclosures—calories, trans fats, added sugars—all in the name of public health. But if the goal was to change how Americans eat, the results remain hard to swallow.

Today, nutrition labels are more accurate and comprehensive than ever, yet 74% of adults in the U.S. are still overweight.

There are many reasons for this discrepancy—highly processed foods are addictive; healthy options are often more expensive. Some have argued that nutrition labels are “a wasteful distraction in the fight against obesity.” But many studies have shown that nutrition labels have their own role to play in nudging consumers to make healthier decisions—with two very big caveats. One: You must care enough to turn over the packaging and study the nutrition info box on the back. Two: You must know enough about nutrition to interpret what’s written in that box.

The Good Food Collective, launching today, wants to tackle both problems at once. The mission of this coalition of more than 25 food brands, organizations, and nutrition experts is to advocate for greater transparency in the food industry. Its first goal is to push for a front-of-package nutrition label that’s visible at a glance and easy to understand and interpret—qualities that can benefit both consumers and food manufacturers. It could change how Americans consume food, and it could change the way companies produce it, too.

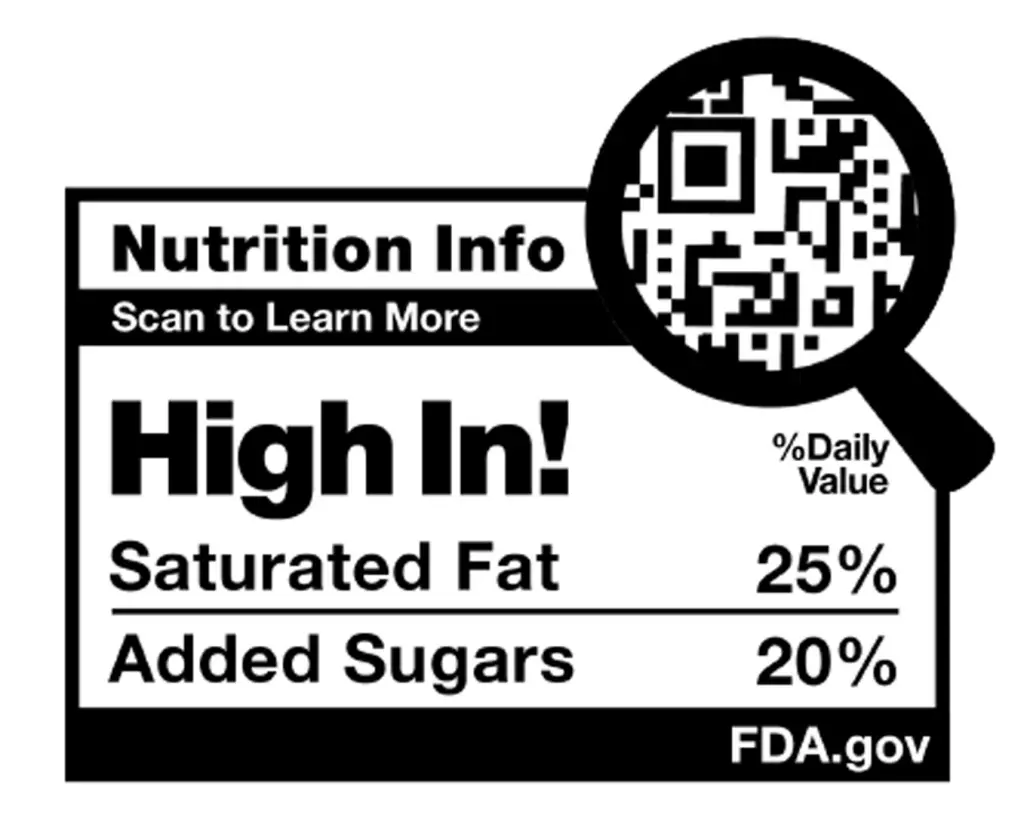

Unlike nutrition labels on the back of packaging, a front-of-package label can catch consumers’ attention during that split-second decision-making moment in the store. The coalition’s design, by branding agency Interact, highlights when a product is high in added sugars, sodium, and saturated fats. It comes with a QR code framed inside a magnifying glass that’s designed to educate people about nutrition, whether at the supermarket or back home. “We’re all working on the same problem, which is undoing years of irresponsible food marketing,” says founding member and GoodPop CEO Daniel Goetz.

The FDA seal of approval

The Good Food Collective isn’t operating in a vacuum. On January 14 of this year—just six days before Donald Trump took office—the Food and Drug Administration proposed requiring a front-of-package (FOP) nutrition label for most packaged foods. By then, the FDA had designed three versions: a simple, text-based label; a traffic light-style, color-coded label; and a black-and-white “percent Daily Value” label. After surveying 10,000 Americans, the agency found that the latter performed best in helping consumers identify healthier food options. The design was then put to a wider test as part of a public comment period that closed just last week, on July 15.

Judging from the docket, the FDA received close to 12,000 comments. Some food manufacturers stated their concern that a label would incur financial costs related to redesigning and repackaging. Others noted that percent daily values like “low” or “high” could be misunderstood without contextual education. The Good Food Collective submitted its design as part of the comment as well.

The FDA has yet to review all the comments, but a lot has changed under the Trump administration. In his capacity as secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. fired 3,500 employees at the FDA, or 20% of its workforce (the FDA did not respond to a request for comment). The Consumer Brands Association (whose members include General Mills, PepsiCo, Unilever, Nestlé, Procter & Gamble, and others) sponsored a study pushing back against front-of-package label efficacy. And Trump introduced a regulatory freeze that’s put many pending rules—including the FOP label—on hold.

If the FDA chooses to go ahead with the proposal, it will publish a final rule in the Federal Register. At that point, manufacturers would have three years to add the new labels, while smaller food manufacturers would have four years.

Nutrition labels around the world

If the FDA decides to implement a front-of-package label, it would follow in the footsteps of about 40 other countries. Some labeling, like in Australia, New Zealand, and the U.K., is voluntary. In Mexico, Chile, Argentina, and Brazil, it’s mandatory. Canada is in the process of implementing front-of-package labels by 2026 for products containing high sodium, sugar, and saturated fat. Singapore is due to extend its label from beverages to foods in 2027. Japan is currently piloting a front-of-package system.

Multiple reviews and real-world trials have shown that front-of-package labels have improved customers’ understanding of nutritional quality and, in the case of New Zealand, the Netherlands, and Chile, even prompted manufacturers to reformulate products. After Chile’s Food Labeling and Advertising law went into effect, the percentage of products qualifying for a high-in-sugar label fell from 80% to 60%, while high-sodium products dropped from 74% to 27%.

It’s important to note that labels are more likely to succeed if they are accompanied by widespread consumer education campaigns to help the public understand how to interpret the labels. The look of the labels matters, too. Simple designs like traffic lights (U.K.), star ratings (Australia and New Zealand), or clear warning symbols (Mexico) have proven more effective than complex or purely numerical labels.

Designing a front-of-package label

The label that GFC is proposing is a direct response to the one proposed by the FDA. At first glance, it doesn’t even look that different. Like the FDA’s version, it’s black and white and mostly laid out in the same way—a wise move that piggybacks on the agency’s research.

But there are some key differences, the biggest being the way information is presented. The FDA’s version gives a breakdown of all key nutrients and whether they are “high,” “low,” or “medium.” The GFC label highlights only nutrients that qualify as “high” in content.

One of the comments submitted to the FDA, by the National Milk Producers Federation, objected to the proposal for a front-of-package label, stating it provides an incomplete assessment of a food’s nutritional profile by focusing only on the bad. But members of the Good Food Collective argue that positives like “organic” or “high in protein” tend to cloud people’s judgment. For example, a product may be high in protein but also high in saturated fat. By focusing on “high in” nutrients, the GFC label makes it harder to avoid the mountain of fat or sodium lurking in that ingredient list.

To further draw attention to the label, the Interact team added a visual nugget in the form of two widely recognizable symbols: the QR code and the magnifying glass. Dan Gladden, Interact’s executive creative director, calls these “memory structures” because the average American is already familiar with them. The QR code is now ubiquitous. The magnifying glass is a clear invitation to find out more.

Interestingly, Interact took cues from the FDA and shied away from using colors in favor of a monochromatic design. According to Gladden, whenever people see a red label, as they do on a bag of crisps in the U.K. (what Americans call potato chips), their inner child might kick in and reach for what they can’t have. “Americans like their freedom, and don’t like to be told what to do,” Gladden says.

Studies have shown that people browsing in a supermarket make a decision in as little as three to five seconds. A black-and-white graphic that calls out “high in” ingredients is easier to interpret than one that, for example, requires parsing out the meaning of a yellow symbol and what about that particular product makes it yellow.

Rising tides lift all boats

At the time of this writing, the Good Food Collective is a coalition of 26, including founding members GoodPop, LesserEvil, Quinn, and Interact, and brands that joined later, including Little Sesame, Dr. Praeger’s, Rudi’s Bakery, and Sweet Nothings.

All brands bill themselves as healthy, which of course could mean that a front-of-package label may translate into higher sales, but it’s hard to be cynical when the outcome could benefit consumers as well. In any case, Tanner Smith, director of retail sales at Little Sesame, isn’t convinced a front-of-package label will lead to increased revenue. “Hummus is a cleaner category anyway,” he told me, referring to Little Sesame’s core offering. “My mind goes to chips, where brands can put a lot of additives.”

Tanner believes the GFC label, the QR code in particular, provides a huge opportunity to educate consumers on making better food choices. “People are more aware of ingredients so I really do hope it does have impact,” he says.

Caitlin Mack, VP of marketing at LesserEvil, is also hopeful it will help brands reformulate their ingredients. “Ultimately, if it’s so in your face, then you’re going to want to make sure it’s coming across as something that consumers are going to want to be consuming,” she says.

Whether or not the FDA takes the GFC’s recommendation, the mere fact that the coalition exists brings a glimmer of hope for the food industry. Many of these brands have been working toward the same goal for years—clean ingredients, honest marketing—but by banding together, they hope to prove that rising tides lift all boats. “What we’re trying to do is, for the first time, be food companies that actually want to see progress on behalf of consumers,” says Goetz. “That’s the spirit of the Good Food Collective.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0