Why State Bags went stealth about its philanthropy

Scot and Jacqueline Tatelman never planned on launching a backpack startup—much less a cult brand that now generates $100 million a year in revenue. Each of them had spent their childhood summers going to idyllic places for sleep-away camp, and they wanted kids from under-resourced communities to have this life-changing experience.

In 2009, when they were in their early twenties, they started a nonprofit that brought students from Brooklyn and the Bronx to the wilderness, where they could eat s’mores around a campfire. But every year, their hearts broke to see how the children toted their stuff. “Many brought all their things in trash bags or plastic Duane Reade bags,” says Scot. “One time, when we were catching a train, a girl’s bag ripped, so all her things were on the platform. These were kids who lived less than two miles from us in New York.”

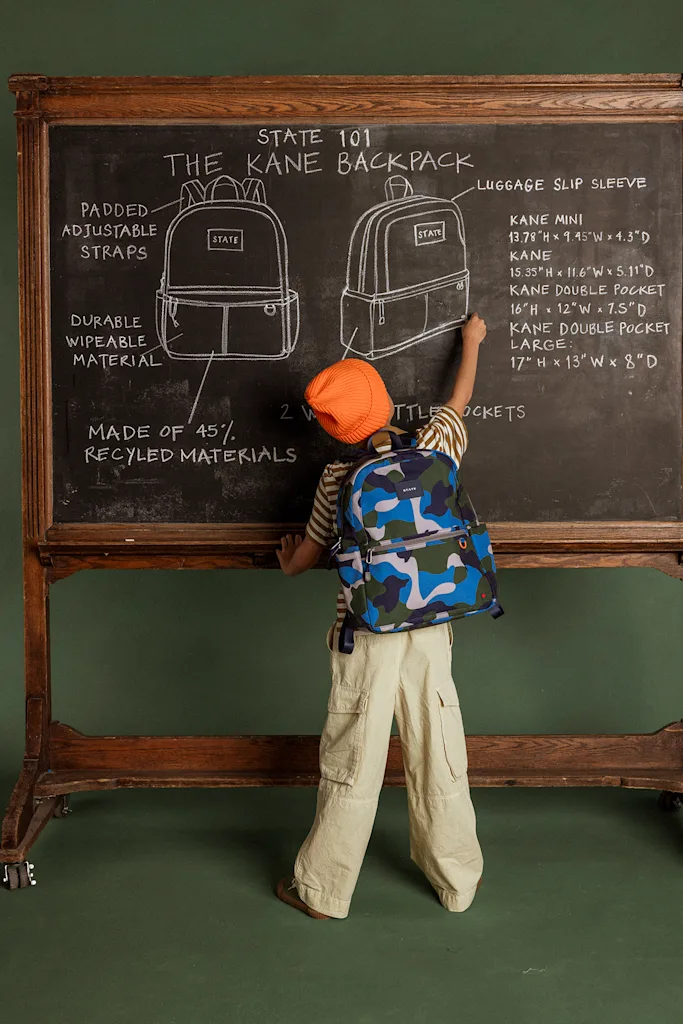

The kids needed better bags, the Tatelmans agreed. At the time, Jacqueline was pregnant, but since her family had been in the fashion industry, she felt she had the skills to start a buy one, give one backpack business. In 2013, they cofounded State, which sells high-end backpacks and uses the proceeds to donate backpacks (and other resources) to kids in need. “We made the deliberate decision to focus on the premium end of the market so we would have enough margin to donate to the philanthropic efforts,” Scot says.

Jacqueline focused on the business, first as chief creative officer. In 2020, she decided to take on the role of CEO as State faced financial challenges, and has since increased revenues by 1,000%, rocketing the company to eight figures in revenue. Scot, meanwhile, has been laser focused on the nonprofit. Every year, Jacqueline apportions hundreds of thousands of dollars to support Scot’s work, from donating backpacks to organizing summer camps.

During the pandemic, Scot pivoted to focus on one-on-one tutoring to kids in New York who were falling behind academically. If the company exceeds its financial targets, it pours more money into the philanthropic work the following year.

Scot says that it has always been tricky being a mission-driven brand. This is particularly true now, when the Trump Administration is attacking companies that engage in diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts. But he’s found that even when social justice was fashionable, it was still hard to communicate about the brand’s work. “There was a time when every brand said it was mission-driven,” says Scot. “Consumers began to see it as a cheap marketing ploy. And now, when you’re committed to social justice you have a target on your back. You just can’t win.”

Now, Scot believes that the best approach to corporate philanthropy is to under-communicate, but over-deliver. After all, the evidence suggests that most consumers don’t make purchases based on a brand’s social mission—and the small number that do will be on the lookout for these efforts, and hold a brand’s feet to the fire if they don’t follow through.

The pendulum of corporate philanthropy

When the Tatelmans launched State, it was the norm for startups to describe themselves as mission-driven. Millennials seemed to care more about brands’ ethics than previous generations did and in the mid-2010s, a wave of direct-to-consumer startups positioned themselves as brands that made money while also doing good.

Warby Parker and Bombas gave away products for each one they sold. Everlane vowed to eradicate virgin plastic from the supply chain. Allbirds and Reformation made eco-friendly sneakers and clothes. Over time, larger companies from Nike to Coca-Cola also aligned themselves with good causes. In 2020, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of the police, even more companies began supporting DEI.

Scot felt ambivalent about this shift toward corporate activism. On the one hand, it validated his thesis that “business for good” was possible. But on the other, it was so ubiquitous that consumers became skeptical when a brand touted its good deeds. This is when State made the decision to communicate less about its mission. “The conversations on social media around mission felt opportunistic,” he says. “I didn’t want to add to the noise.”

Just a few years later, the corporate landscape is unrecognizable. The Trump administration and right-wing shareholders have demanded that companies abandon their DEI initiatives, and many have complied. Companies once seen as beacons of progressive values—like Target and Google—have pulled back from their DEI programs. As James Surowiecki argues in a Fast Company article, shedding social justice and philanthropy efforts was also a way to cut losses.

And on the surface, State also seems primarily focused on selling products. There are clues about the brand’s philanthropic efforts, including the company’s “about” page and an occasional Instagram post. “We’ve found that the best and most authentic way for people to learn about the mission is organically, as opposed to shoving it down their throat,” he says. “If they want to know more, they’ll dig deeper. But many will not, and we’re okay with that.”

While consumers report that corporate ethics matter to them, this hasn’t been borne out in their buying behavior. In 2024, scholars from the University of Chicago and New York University tracked the spending habits of 24,000 consumers. While most stated a moderate preference for ethical companies, it ultimately had no impact on what they bought. And this was before the mood in the country shifted.

So what’s the point of corporate philanthropy?

All of this surfaces the question of whether it is worth launching a mission-driven business at all. Does it make more sense for nonprofits and companies to stay separate? Scot doesn’t think so.

For one thing, he believes a social mission is a good way to keep employees engaged. At State, staff can devote part of their time to working on philanthropic projects, from back-to-school backpack drops to helping to plan camps. Jacqueline says the brand’s mission has also helped her stay focused as CEO. “Running a business is hard,” she says. “We have been through very difficult times as a business, but having larger goals—and people we don’t want to let down—really helps us stay motivated.”

Jacqueline also believes that some consumers are more loyal to mission-driven brand. While they make the initial purchase because they like the backpack’s design and quality, they may learn more about State’s philanthropic efforts over time. And if they feel good about their purchase, they are more likely to buy another backpack in the future.

Utimately, Scot hasn’t given up on the idea that a business can be force for good in the world. Some companies were clearly serious about their mission, given how quickly they abandoned their philanthropic efforts. But others have stayed the course regardless of the political climate, including Patagonia, Levi’s, Ben & Jerry’s, and Costco.

And these companies can continue have a positive impact on many people at a time when many nonprofits are dealing with cuts to their funding. “Many communities that are struggling because companies offered to help them but are now retreating,” he says. “We really need more companies to step up and fill in the gaps.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0