The trouble with Agent, ChatGPT’s new web-browsing AI

Hello again, and thanks for reading Fast Company’s Plugged In.

When you think about it, training AI to use the web might be the single most impactful way to expand its power. So much of what we do today—from buying products of all kinds to managing every aspect of our personal data—we do online. If a piece of software could handle that work at least as well as a human, it could be a far more essential assistant than any existing AI tool.

Web savvy is key to the tech industry’s current yen to make AI more agentic—that is, capable of performing multistep processes on our behalf with some degree of autonomy. A flurry of recent news reflects this trend. On July 9, for example, Perplexity launched Comet, a web browser with a built-in AI agent, available mostly to users of the company’s $200/month plan. A week later, OpenAI began rolling out a new ChatGPT agent called . . . Agent. Microsoft is adding a Copilot mode to its Edge browser that it says will soon be able to perform tasks such as making reservations; Opera is previewing Opera Neon, its own browser with built-in agentic AI.

I’ve been playing with OpenAI’s Agent, which showed up in my ChatGPT Plus account earlier this week. The company’s blog post on the feature raises expectations by describing it as “already a powerful tool for handling complex tasks.” So far, however, my experiences with it have not provided any moments of awe and wonder.

Instead, I’ve been left wondering if the era of offloading all kinds of web work to an LLM is further off than I thought. Tech companies have already trained AI to do some astonishing things, such as achieve gold-medal-level performance in the International Mathematical Olympiad. But Agent often came off like a clueless internet newbie banging its head against a medium conspiring to foil it.

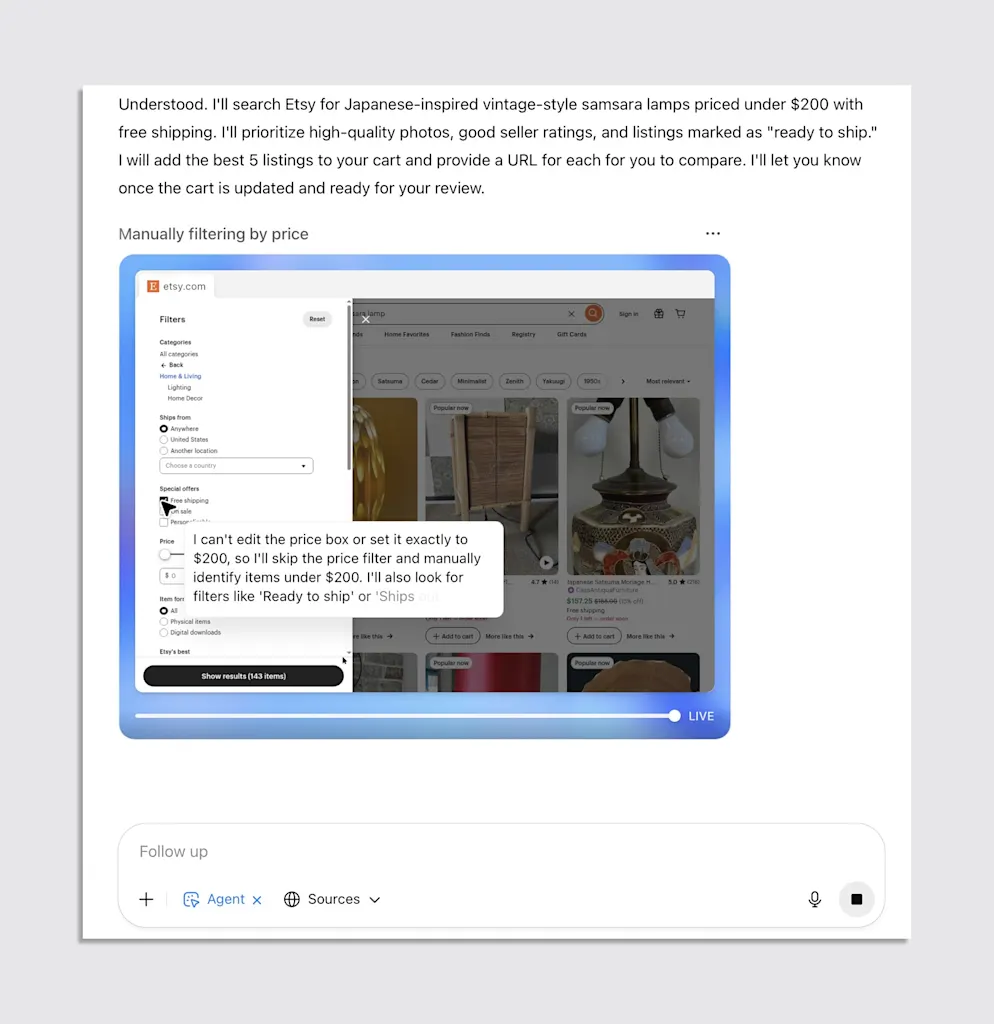

In its own odd way, watching Agent at work is fascinating. When you give it a prompt—as with AI of all types, the more detail you provide, the better—it opens a web browser on a remote OpenAI computer. Then it displays the web pages it’s accessing right inside your chat and explains every step it’s taking in absurd detail, down to which buttons it chooses to click. It’s like peering into the feature’s brain, and underscores the infinite number of tiny, almost subconscious decisions we make when using the web.

More often than not, though, Agent’s responses to my requests weren’t worth the wait. It took 13 minutes to rummage through Google Flights for San Francisco-New York flight options, and the list it gave me was missing the itinerary I probably would have chosen. When I asked it to compile a list of the necessary ingredients to bake authentic German lebkuchen, it combined ones from two different recipes without any apparent logic. I fed it the description for a job opening here at Fast Company and asked it to find candidates; it suggested some, but with out-of-date information on their current employers.

After a certain point, I wondered whether the projects I was throwing Agent’s way were poor tests of its talents. So I tried several tasks ChatGPT suggests when you initiate an Agent session. Many of them, it whiffed. Agent could not log into my Wall Street Journal account to prepare a report on the site’s coverage of rare earth materials, or verify my phone number to schedule an Uber pickup. While adding banana cream pie ingredients to an Instacart order, it plugged in a random delivery address and didn’t seem to offer any way for me to correct it. A summary of Axios’s recent articles on AI worked better, except it didn’t include anything from the past two weeks. (Agent was often confused about the current date, informing me at various points that it was July 15 or July 16 when it was actually July 30.)

Because Agent discloses what it’s doing so thoroughly, it’s possible to hazard some guesses about why the results aren’t better. First of all, it was frequently bogged down by what it concluded were errors on its part or website malfunctions—“It seems the previous click didn’t work as expected”—though it wasn’t always clear whether anything had in fact gone wrong.

Secondly, the internet as we know it is designed for the convenience of humans, not to facilitate AI agents. Indeed, many sites (including, ahem, FastCompany.com) block automated browsing of the sort Agent performs.

In my experience, this blocking was a persistent obstacle to Agent, which kept encountering “Are you human?” tests. Unfazed, it tried increasingly ambitious work-arounds, such as translating a Fast Company story that had been translated into Spanish back into English. But that turned theoretically simple projects into slogs, almost always with diminishing returns.

Lastly, there’s the question of privacy and security. Agent is designed to let you type login information for your accounts into its remote browser, though it didn’t always work for me. Many folks might be disinclined to even try it, given that it involves handing your passwords over and trusting OpenAI to use them responsibly.

In the interest of researching this newsletter, I signed into my Gmail account and asked Agent to compile a few reports on the messages therein. Correctly identifying it as a sensitive situation, Agent insisted I monitor its work and paused it whenever I tabbed away—negating any time I might have saved by not performing the job myself.

Access to the user’s personal data is essential to Agent realizing even a fraction of its potential, since the better it knows us, the more sophisticated its help can get. For example, I try to book an aisle seat when flying alone but grab myself a middle seat if my wife is along for the flight—a habit a truly clever AI might be able to divine from my travel history without me explicitly stating it. But OpenAI hasn’t yet given the feature anything resembling an uncanny ability to understand such needs and desires.

For now, Agent often turned out to be a slower way to achieve a goal than existing web tools that are mature and predictable. I was heartened when I asked Agent to find the lowest price on a particular Casio music keyboard: It found it on eBay and added it to my shopping cart. Except that a Google search returned the same eBay listing as its first link. And clicking the “Add to cart” button oneself does not exactly amount to heavy lifting.

The thing is, we already have tools designed to give software, such as an agent, efficient access to other software. They’re called APIs, and instead of expecting an app to puzzle its way through browsing the web, typing into forms, and clicking forms, they let it transmit requests and retrieve results as streams of raw data. APIs only support processes that the host software has chosen to make available rather than the theoretically open-ended capabilities of an agent. But they do it quickly, easily, and without requiring the user’s attention.

Agent does support an existing API-based ChatGPT feature called Connectors, but this, too, was flaky in my experiments. When I issued a Gmail-related request, it didn’t point out that there was a Gmail connector but I hadn’t installed it. Instead, it had me log into my account and supervise its browsing. Another time, I tried a task involving OneDrive and Agent suggested, fuzzily, that there might be a relevant connector. (There is.)

I’m not discounting the possibility that Agent, or someone else’s agentic web-browsing AI, will get radically better in manifestly obvious ways. Some degree of improvement is inevitable. Yet the tool, in its current state, is another reminder of how far the industry’s lofty proclamations have raced ahead of actual progress.

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg, and others have lately said that their goal is superintelligence—AI that’s better than humans at everything. Using a web browser hardly ranks among the world’s most intellectually taxing activities. But until AI masters it, superintelligence will be a talking point, not a reality.

You’ve been reading Plugged In, Fast Company’s weekly tech newsletter from me, global technology editor Harry McCracken. If a friend or colleague forwarded this edition to you—or if you’re reading it on FastCompany.com—you can check out previous issues and sign up to get it yourself every Friday morning. I love hearing from you: Ping me at [email protected] with your feedback and ideas for future newsletters. I’m also on Bluesky, Mastodon, and Threads, and you can follow Plugged In on Flipboard.

More top tech stories from Fast Company

How Google is working with Hollywood to bring AI to filmmaking

Mira Lane, who runs Google’s Envisioning Studio, talks about how artists are embracing tools like Google’s Flow for preproduction, previsualization, and prototyping.

Read More →

Exclusive: Reality Defender expands deepfake detection access to independent developers

The cybersecurity company has launched a public API and a free tier that allows up to 50 detections per month.

Read More →

‘The overall vibe was total chaos’: Tesla Diner goes viral for long waits and mixed reviews

Elon Musk’s retro-futuristic restaurant is blowing up online as TikTokers share their experiences.

Read More →

The Trump administration might overhaul the U.S. patent system

The Commerce Department is considering charging patent holders between 1% and 5% of their overall patent value.

Read More →

Software nearly ate the world. Now builders and designers are taking it back

What’s behind the New Industrials movement—and why it matters

Read More →

Starbucks was a pioneer of the mobile-first shop. Now its getting rid of them

Starbucks is sunsetting its mobile-order and pick-up-only store format as part of a strategy to elevate its café experience.

Read More →

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0