AeroFarms turned itself around after bankruptcy. Is it a sign that vertical farming can succeed?

After raising billions in funding, vertical farming companies have struggled. Plenty, a Silicon Valley-based startup backed by investors including Jeff Bezos and Eric Schmidt, filed for bankruptcy in March. Bowery, which was once valued at $2.3 billion, shut down last fall. Another startup, Fifth Season, shuttered its automated indoor farm in 2022. AeroFarms, a pioneer in the space, declared bankruptcy in 2023.

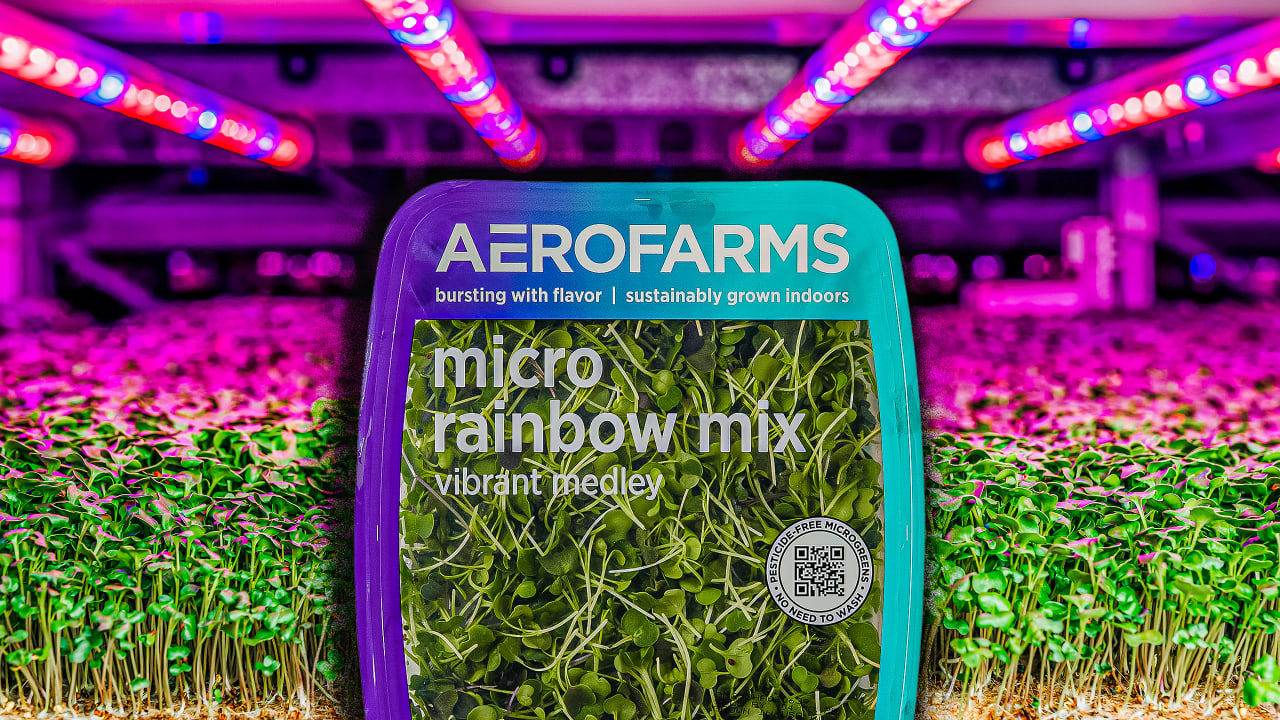

The basic business model—growing crops like leafy greens indoors on tall vertical towers—hasn’t proven that it can work. But AeroFarms, which raised an undisclosed amount of money after its bankruptcy and found a new CEO, has managed to turn itself around. The company has now been profitable for the last two quarters as it sells microgreens at retailers like Whole Foods and Costco.

“Despite the current skepticism, I think we’ve now demonstrated that vertical farming can be sustainable and profitable and deliver product at scale,” says Molly Montgomery, who became CEO of AeroFarms in September 2023.

Before joining the company, Montgomery studied it at the request of investors who wanted to know if it could be a viable business. “I was extremely skeptical about vertical farms because I had never seen a profitable business model yet,” says Montgomery. “When they asked me, I was like, ‘I’m not sure that a vertical farm can be profitable.’” Montgomery, who also serves as board director for NatureSweet, a leader in greenhouse-grown tomatoes, previously led Landec Corp., a company that contracted with outdoor growers throughout the U.S. and Mexico to make salad kits and other packaged vegetable products.

But doing the due diligence on AeroFarms convinced her that it could actually succeed. She calculated that AeroFarms’s technology could operate at the right production cost. And consumers liked the product, particularly its microgreens, tiny greens that are harvested when they’re 4 days old.

“The missing ingredient was operational excellence,” she says. “There wasn’t enough experience in the company on how to run a vegetable production facility.”

It was a tech company first, not a farming company. Montgomery’s initial step was to focus: She shut down R&D facilities in New Jersey and Abu Dhabi, so all that was left was a 140,000-square-foot production facility in Virginia that had opened in 2022. Half of the staff was laid off. “Everyone who was left was put on specific initiatives that I believed would enable us to get to farm profitability,” she says. She also hired employees with deep expertise in food production.

The team went through several sprints on the basics, from food safety to training employees. Then it focused on operational issues like how to improve yield and how to maintain the robots that grow the crops. The company’s automated system loads plants in the tall towers where they grow, monitors and harvests the crops, and packs up products for stores. (It runs 24/7 and has more than 2,000 spare parts, meaning that maintenance is a major task.)

Montgomery also chose to focus on microgreens, which have better margins than traditional leafy greens. The company grows a variety of crops, from kale and cabbage to bok choy and spicy wasabi mustard. The young greens are more nutritious than fully grown versions of the same crops. It’s not something that was ever readily available from traditional farms. When they’re grown outside in soil (and often with pesticides), they have to be washed, which harms the dainty plants. “As soon as you wash them, they begin to decay,” she says. “So [they have] a very short shelf life. When you grow them aeroponically, we don’t use any pesticides and we only spray the roots. So we do not need to wash them.”

That means, she says, that AeroFarms’s greens have a shelf life that lasts as long as 24 days. The company currently supplies around 70% of the retail market for microgreens, and is seeing demand for more.

The company’s tech may have some advantages compared to other approaches. It grows plants aeroponically, without soil and without submerging plants in standing water, so the whole system is lighter than some others, and more plants can be stacked vertically, making better use of floor space. Misting the roots with water and nutrients speeds up the plants’ growth rate. Because the farms can be more productive than competitors, the company can use less energy per plant; energy is one of the biggest factors in the cost of running a vertical farm.

If vertical farming can work, there could be clear benefits. Right now, most greens in the U.S. come from drought-prone regions like Arizona and California; vertical farms use 90% less water than growing outside. As climate change makes farming more difficult—especially because of extreme heat—indoor farming could theoretically help support the supply chain. And instead of shipping produce thousands of miles across the country, East Coast grocery stores could get more of it locally year-round.

The industry is still nascent, and two profitable quarters aren’t conclusive proof that vertical farming can succeed. Still, it’s a sign of hope for a teetering field, and AeroFarms is once again planning for expansion.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

![Britz unites cultures and sounds on summer anthem “Ghanaman” with Pacify and NSG [Video]](https://earmilk.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Britz-NSG-Pacify-scaled.jpg)

![Andy Tongren launches solo project with anthemic "So Good" [Video]](https://earmilk.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/ANDY-RETOUCH-1.jpg)