Climate tech startup Brimstone just lost a $189 million DOE grant—but it’s building its first plant anyway

Last year, Cody Finke got game-changing news from the Department of Energy (DOE): his climate tech startup was in line for a $189 million grant to help build its first commercial-scale plant. The company, Brimstone, has developed a new way to make cement—one of the biggest sources of carbon emissions on the planet.

The startup also makes smelter-grade alumina, a critical mineral that the U.S. currently imports. The team spent months going through the DOE’s grueling evaluation process, from a 200-page application to a three-hour-long interview in front of a panel of 30 technical experts. After the DOE moved the project forward, months of negotiations followed. The grant was finalized in January, just before the inauguration. Then came the Trump administration.

This summer, the DOE announced that it was pulling the funding, along with grants for more than 20 other projects working on industrial decarbonization and carbon capture. Brimstone is appealing the decision, since producing critical minerals in the U.S. is a priority for Trump. But the company is also moving forward with its plans to build its plant regardless of what happens with the government funding.

“Our belief has been from the beginning that our technology has to work without subsidies,” Finke says. “And if it doesn’t work without subsidies, then it probably isn’t going to have the impact we want.”

Tech built for the bottom line—not just carbon cuts

Brimstone’s technology tackles an industry that’s notoriously hard to decarbonize. Cement production is responsible for around 8% of global CO2 emissions, or three times as much as the airline industry. That’s not just because of the energy it takes to make cement, but because of chemistry: Typical Portland cement is made by heating up limestone, and that process releases CO2 from the rocks.

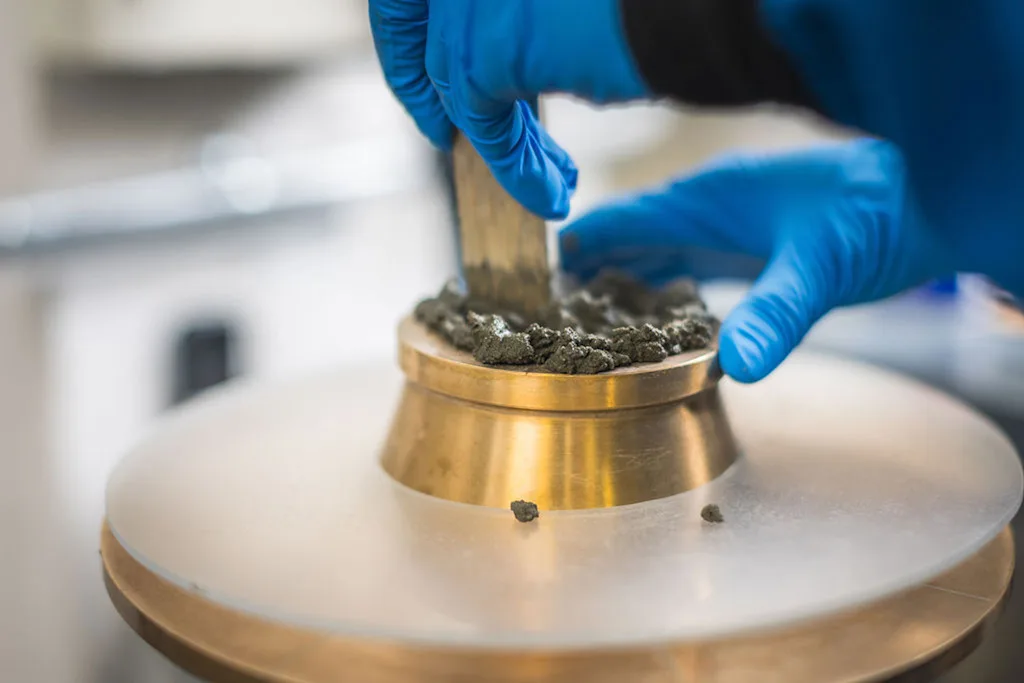

The startup uses silicate rocks instead, such as basalt, which don’t release CO2. If the new process runs on renewable energy, the result is zero-carbon cement. If it uses the mix of energy on the grid, the emissions reduction could still be as much as 75%. If it can be widely scaled up in the industry—which produces more than 4 billion tons of cement each year for everything from roads and bridges to homes—it could make a significant dent in global emissions.

From the beginning, when Finke first started developing the idea with his cofounder as a grad student at Caltech in 2019, he calculated what could make it economically viable. The new process had a fundamental advantage—instead of making CO2 as a byproduct, it makes valuable materials that can be sold.

Valuable byproducts

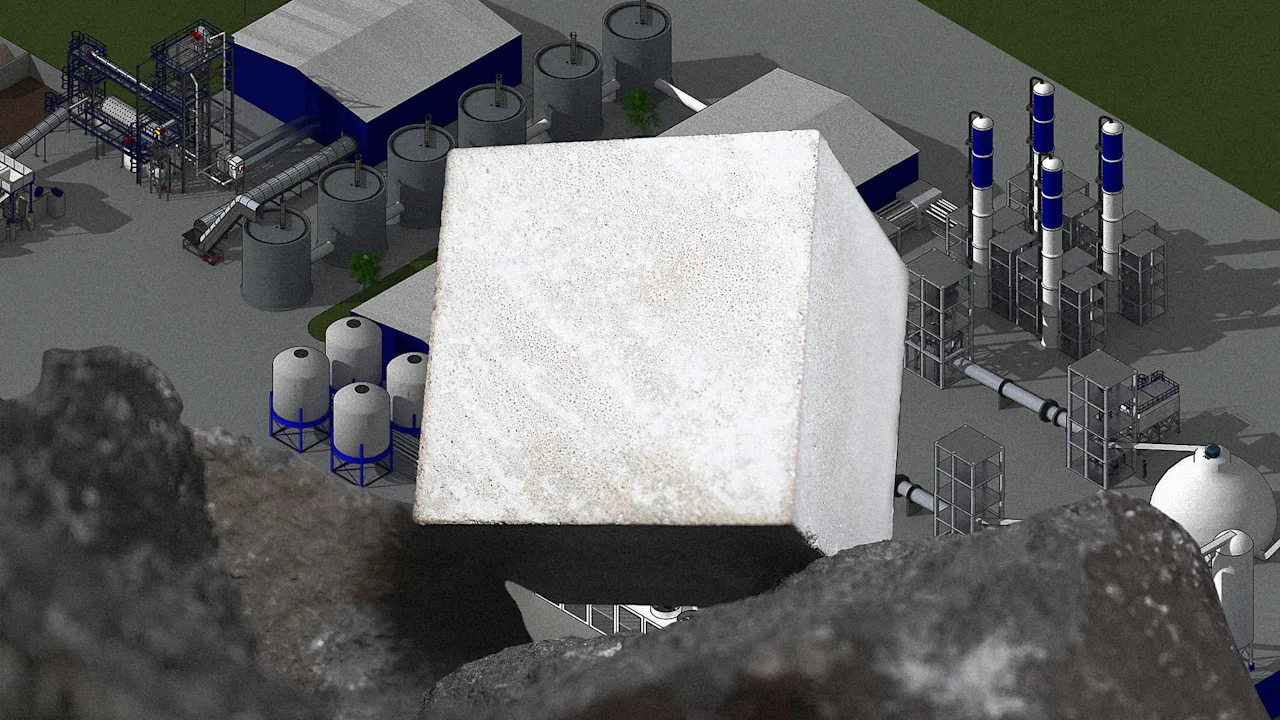

The first plant will mine rocks that are especially high in alumina, which can be used to make aluminum. The process is fairly straightforward. The company crushes the rocks into particles, and then uses chemicals to extract calcium for making cement. (The calcium is heated up, and then milled with gypsum.) Other residue becomes the SCM (supplementary cementitious materials), another product that’s used to make cement. Aluminum compounds are extracted separately.

By making and selling more than one product from the same rock, all of the products—including the low-carbon cement—can be cost-competitive when they’re produced at an industrial scale. The process is inherently more efficient. Right now, other companies make cement, alumina, and SCM separately, and start each process by mining and grinding rock.

“It’s three separate instances of mining and grinding,” Finke says. “We have one instance of mining and grinding, which means that we only have to develop a rock with a single quarry. We only have to have a single piece of equipment, and that piece of equipment can be larger, and then therefore benefit from economies of scale.” The company will mine seven times less rock for its products than the standard processes today.

Strong demand

While some other companies are making low-carbon alternatives to cement, Brimstone wanted to make ordinary Portland cement—the standard product already in use in the building industry. Brimstone’s cement meets ASTM International’s standards for Portland cement. It’s exactly as strong and durable and capable of handling extreme temperatures or chemical exposures. The SCM and alumina are also the same as what’s already on the market.

“We make the exact same products,” Finke says. “Since these are all structural materials, we think that’s really important—no one wants to take a risk on structural components.”

Large customers already want to buy it. Amazon, for example, recently announced plans to reserve volumes of the cement and SCM from the upcoming plant. The tech giant recently went through rounds of third-party tests of the materials, proving that it met requirements for strength and other factors. Amazon has also invested in the startup through its Climate Pledge Fund.

Since the first plant will be a demonstration plant, the initial cost of the products will be higher, but companies like Amazon are willing to pay a premium. There’s strong demand, even as some companies are now less vocal about climate goals.

“There are certain companies that care deeply about green attributes, and there are certain companies that don’t,” says Finke. “I think that the number of companies have changed somewhat, but the number of meaningful companies has not really changed. We see that steadiness.”

A careful funding strategy

Brimstone has raised more than $80 million to date from investors including Bill Gates’s Breakthrough Energy Ventures. As the team raised money, it never counted on the inevitability of government grants.

“These subsidies are sort of at the political whims of any one party, and we don’t want our technology to be [subject to] political whims,” Finke says. “We want to have a solid economic footing. And that means that we need to have a fundraising strategy that doesn’t count subsidies until the dollars are in our bank account.”

The DOE money was reimbursement-based, so funds would have been given out when the project hit certain milestones. It was also focused on funding for the final stages of building the plant.

Because the company hadn’t counted on that funding, it has money available now to continue working on the project. The company recently announced that it was partnering with a quarry in Oklahoma, Dolese Bros., after evaluating 23,000 different quarries across the country. The location of the new plant, called the Rock Refinery, is being finalized now. It plans to begin operations by the end of the decade.

Looking ahead

The company isn’t disclosing its fundraising strategy, though it says it has investors in place to help it continue building. Of course, the grant could have helped the company move even faster.

The company’s policy team continues to work on its appeal for the grant. “Smelter-grade aluminum is a critical material that the United States cannot make,” Finke says. “The Trump administration is very interested in critical materials. And what we like to say is that if the Trump administration put out a grant for critical materials, we would have applied to that grant—basically the exact same project.”

But the appeal process isn’t delaying the current work to build the plant and plan for future growth. “Subsidies would help our costs, absolutely,” Finke says. “But if it’s necessary to have those subsidies, it’s not likely to scale globally.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

![Wednesday Part 2 Trailer Brings [Spoiler] Back from the Dead, Teases Lady Gaga’s Arrival](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/wednesday-season-2-part-2-release-date-trailer.jpg?#)