How a ‘Shark Tank’-winning neuroscientist invented the bionic hand that stole the show at Comic-Con

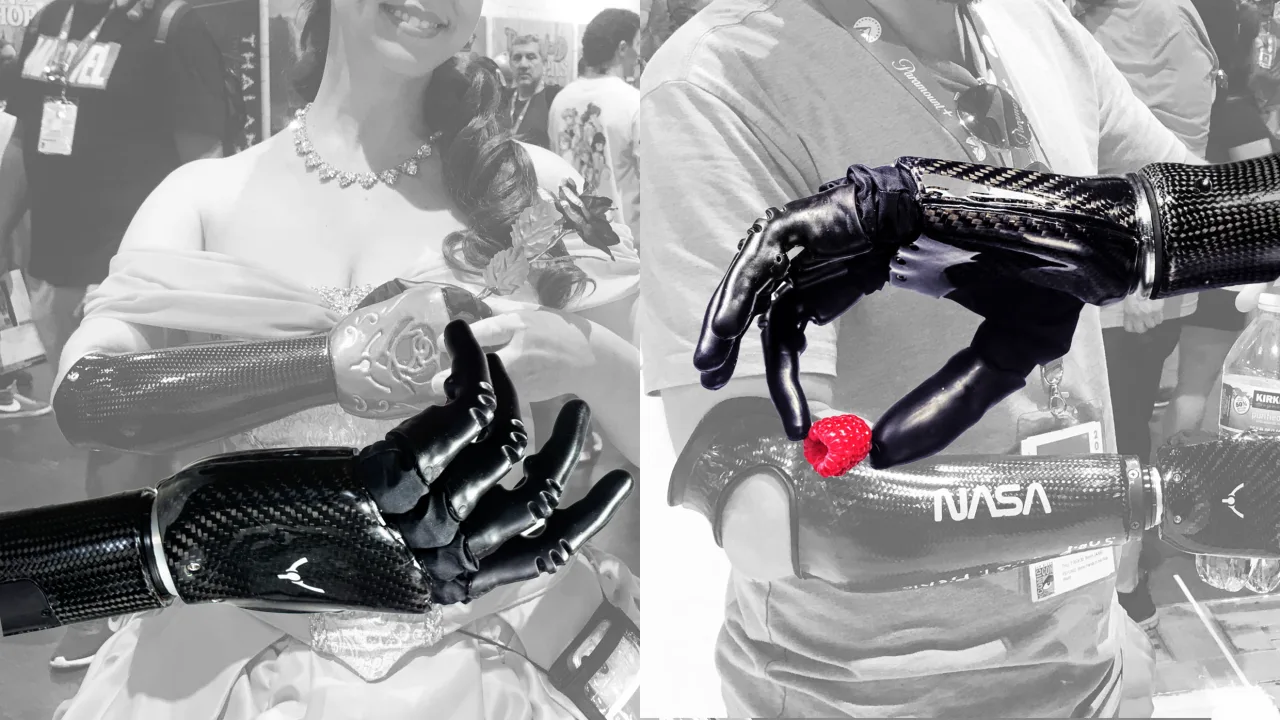

A gleaming Belle from Beauty and the Beast glided along the exhibition floor at last year’s San Diego Comic-Con adorned in a yellow corseted gown with cascading satin folds. She could barely take two steps before a cluster of little girls stopped her for photos. As she waved one hand, her other delicately held a red flower with mechanized fingers. The kids stared. It’s not every day you see a fairy-tale princess with a cybernetic hand. Disney meets Skynet. But this being the epicenter of the nerd universe, the mash-up slayed. “Oh, cooool,” one of them cooed.

For Mandy Pursley, the 42-year-old graphic designer cosplaying Belle, it was a chance not only to show off her enviable sewing chops, but also to display the bleeding-edge technology that overhauled her life. Pursley was born with a right arm that ended just below her elbow. She began wearing prosthetics at age 6 but grew disillusioned with them a few years later. “I didn’t find it to be very functional or very useful,” she says.

Over time, her left hand overcompensated. She accomplished tasks like typing 60 words per minute, but more nuanced dexterity eluded her. That is, until three years ago, when Pursley began using the Ability Hand, a state-of-the-art bionic prosthetic from San Diego startup Psyonic. Marketed as the first and fastest touch-sensing myoelectric hand, the device translates arm muscle movements from the residual limb into electronic signals that control the hand, while a haptic motor vibrates to indicate how tightly items are being grasped.

The results were game-changing. Before, Pursley often held objects with her feet. Now she tackles mundane tasks like opening a water bottle or threading a needle much more conventionally. “I’m able to use jewelry pliers now when I’m doing my costume making,” she says. “Before I would put the pliers in my armpit. It would hurt, and I didn’t have a lot of control over the really fine motions, like opening and closing them.”

Pursley wasn’t the only bionic cosplayer at Comic-Con. She was part of a posse of Psyonic clients alongside Aadeel Akhtar, the firm’s 38-year-old founder and CEO and Ability Hand inventor, coursing through the convention after their panel, “Psyonic: Bionic Arms in the Real World,” which returns to this year’s event on July 24.

“It’s the world’s premier conference for sci-fi,” Akhtar says. “This is the current state of bionic technology, and what’s happening in science fiction is becoming a reality. We can demonstrate it at San Diego Comic-Con and show the world the cool stuff our users can do.”

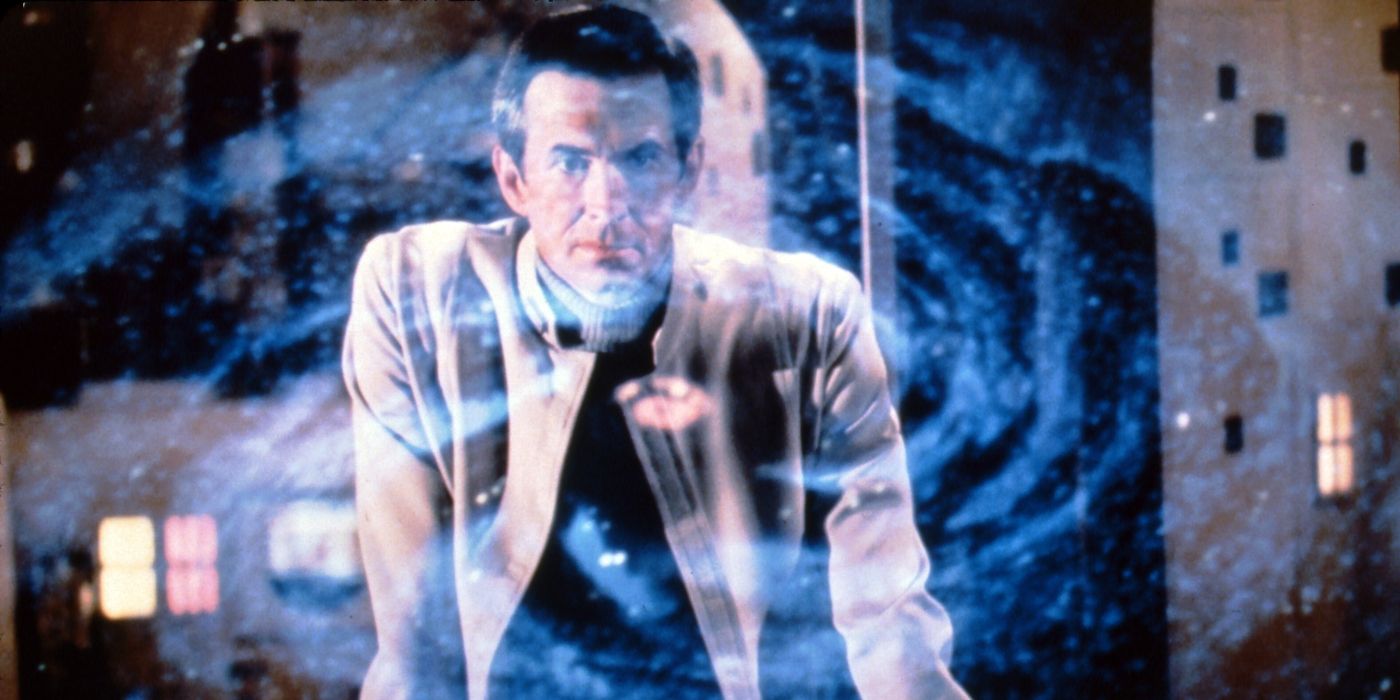

Their presence is a natural here, given the pervasiveness of high-tech prosthetics in the sci-fi and comic universes. Marvel’s Bucky Barnes and Mad Max’s Furiosa sport bionic arms, while characters in the anime series Fullmetal Alchemist boast a range of mechanized limbs (not to mention the robotic hand Luke Skywalker receives in Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back after Darth Vader severs his real one).

But it wasn’t just sci-fi fans. The technology also caught the attention of science and film luminaries. Retired NASA astronaut Cady Coleman and Captain America: Brave New World production designer Ramsey Avery, at SDCC for panels, stopped to chat with Akhtar and examine the Ability Hand.

Avery recalls being awestruck by the machinery: “After years of cheating fake versions of functional artificial arms to look real for film or theme parks, there it was, the real thing!” Avery is returning to Comic-Con this year to conduct portfolio reviews on July 26. “It is so exciting to find myself living in the aspirational versions of the sci-fi I read as a kid, instead of the dystopian ones,” he says.

It’s the same “wow” factor that last year blew away the hard-won Shark Tank judges, three of whom—Lori Greiner, Daymond John, and Kevin O’Leary—agreed to invest a collective $1 million in exchange for a 6% equity stake, the particulars of which are still being negotiated. The device was also featured in a 2023 60 Minutes segment on University of Chicago prosthetic brain implant research.

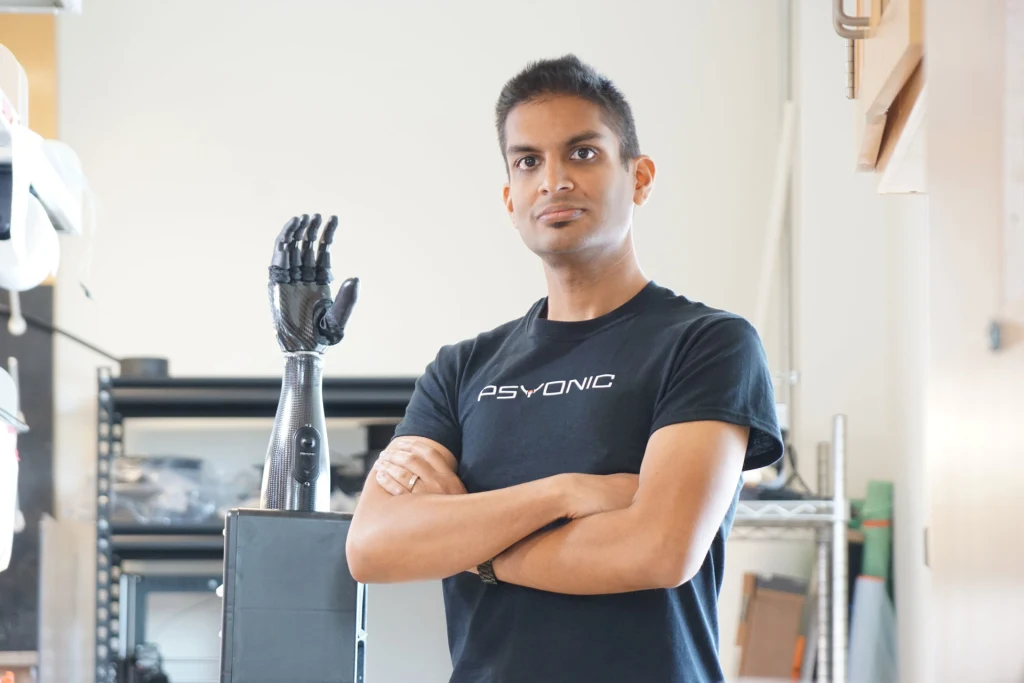

Having amassed $4.1 million from equity crowdfunding and now valued at $65 million, the 10-year-old company has grown to more than 45 employees and broken even with a projected revenue of $6 million this year. It’s now in the process of relocating to a nearby 22,000-square-foot manufacturing facility, almost five times the size of its current digs, and considering an eventual IPO to scale up manufacturing.

Psyonic’s hands are used by nearly 250 patients and more than 50 of the world’s top robotics researchers, institutions, and companies, including NASA, Meta, Google, Mercedes-Benz, and MIT. Nonhuman applications range from automated assembly to service robots. Two years ago, the company introduced Abi the Ability Dog, a demonstration robotic dog that uses an Ability Hand to turn doorknobs and wield lightsabers. Meanwhile, NASA is readying an Ability Hand-sporting humanoid robot named Valkyrie for a future space mission.

“We’re making over 1,000 hands a year, at $15,000 to $20,000 apiece, for both a human and humanoid robot marketplace that will explode in the next five years,” Akhtar says. “But we need to scale this to where we’re making tens to a hundred thousand hands per year. Our biggest issue right now is that we’ve got more demand than we can produce.”

Much of that growth allows putting considerable energy back into innovating. Earlier this year, Psyonic released a lighter, faster, and more durable upgrade with a stronger grip and conductive fingers for cellphone use, with plans to roll out a fully redesigned Ability Hand by 2027. Meanwhile, it’s concurrently working on a next-generation interface enabling more nuanced individual finger control and a localized sense of touch. This approach involves implanting electrodes in the residual limb nerves and titanium rods in the bones. The electrodes carry signals between the nerves and the hand along wires inside the rods.

Akhtar also intends to adapt the technology for partial-hand amputees and to create an Ability Leg. “I see a more seamless interaction between humans and machines, where this feels like an extension of your body as opposed to just a tool on the end of it,” he says.

What makes the tech so special?

The Ability Hand is two and a half times faster than its competitors (closing as fast as 0.2 seconds) and the first with touch feedback, Akhtar says. It attaches to a custom-molded arm prosthetic, or “socket,” that’s made separately by prosthetic clinics, and grips the residual limb by extending over the bony protrusions flanking the elbow. The user’s brain sends signals to the limb muscles as though to move an actual hand, causing them to expand and contract. Two sensors in the socket detect those movements, amplify them, convert them into electrical signals, and transmit them to the Ability Hand, causing the grip to open or close. Users can connect to a smartphone app via Bluetooth to create customized grips and display data such as muscle signals and touch feedback. An internal haptic motor vibrates according to grip strength to let users know how firmly they’re grasping things and give them the sensation of pressure.

Batteries last six to eight hours, depending on use, and recharge in an hour by plugging the socket into a wall. There are also a couple of nifty perks: The hand plays a synthesized version of the Doom video game theme song and can also charge phones. (“I wish I could do that with my natural arm!” Akhtar says with a laugh.) Psyonic offers a selection of colors—blue, white, green, rose gold, and black—and attachments like a wrist rotator that can turn hands 360 degrees.

Both the Ability Hand and socket are typically made from carbon fiber—the same material used in rocket parts—rendering them lightweight but able to take a beating, with silicone and rubber in the fingers enabling flexibility.

“I can smash this, it totally survives,” says Akhtar, waving a model Ability Hand. “I’ve dropped it from the roof of my house, 30 feet in the air. I put it in the dryer for 10 minutes. I’ve stepped on it. We’ve done flaming board-breaking with it. I arm-wrestled a U.S. paratriathlon national champion and lost. It’s also one of the few that’s water resistant, so you can wash it like you would a natural hand, though you can’t submerge it yet.”

That toughness makes more activities possible. “I’m very hard on my prosthetic devices,” says Kate Ketelhohn, 22, who was dressed as Bo Peep from Toy Story. “I do theater, and it would break during a show. The director would want me to do certain tasks and I couldn’t do them because my hand couldn’t handle it.”

A graduate student in bioethics and medical humanities at Case Western Reserve University, Ketelhohn has been using the Psyonic device since her senior year of high school. As an infant, she lost her left forearm, right-hand fingertips, and feet from sepsis and meningitis, and has worn prostheses since she was a toddler. But the muscle-powered hook she used during childhood couldn’t quite cut it.

“The devastation as a kid when you just keep trying to eat chips and keep crumbling them because your hand can’t handle fine delicate movement,” she says. “Now, being able to eat chips or carry food in one hand and eat it with the other feels like a complete life hack. People with disabilities, especially with upper-limb differences, have such possibilities to work and function at a pretty normal able-bodied level if we have access to the right tools.”

A life-changing trip

Akhtar has wanted to build bionic limbs since age 7 after traveling with his parents to their native Pakistan and seeing a girl his age missing her right leg and using a tree branch as a crutch. “It just stuck with me,” he says. “We had the same ethnic heritage, but vastly different qualities of life. A lot of it has to do with having access to things like affordable rehabilitative care and advancements, like bionic limbs.”

He studied biology at Loyola University in Chicago, his hometown, intent on becoming a neurosurgeon, until a computer class captured his imagination. “I loved everything about coding and programming and making my own things. I realized that if I became a straight-up MD I wouldn’t get to do any of the cool stuff I was learning in my computer science classes.” Akhtar also drew inspiration from breakthrough research at the time that used nerve impulses to control prosthetics. “I wanted to figure out a way to merge my interests in prosthetics, clinical medicine, and engineering to help people with limb differences regain function and improve their quality of life.”

Akhtar went on to earn two master’s degrees in computer science and electrical and computer engineering at Loyola and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, respectively. He was on an MD/PhD track at the latter when he got the chance to work with the Range of Motion Project, an Ecuadorian nonprofit that provides prosthetics to those who can’t afford them. Its first patient was Juan Suquillo, an Ecuadorian Army veteran who’d lost his left hand during a 1981 border war with Peru. Akhtar watched Suquillo tear up after donning an early version—three times his hand size, with wires everywhere—and pinching his left fingers together.

“For the first time in nearly 35 years, he felt as though a part of him had come back,” Akhtar recalls. “It was in that moment I realized that if I finished this MD/PhD program and worked at an academic hospital, this would just end up as a journal paper. And if we wanted everyone to feel the exact same way that Juan did, we had to commercialize the technology.”

Thus, Psyonic was born in 2015. Even the name has its roots in comics, inspired by the X-Men characters whose “psionic” powers control matter with their minds. After earning his doctorate in neuroscience the following year, and buoyed by two prestigious university innovation awards for his invention, Akhtar stepped away from medical school (to his parents’ dismay) and began raising money through equity crowdfunding and National Science Foundation grants.

By 2021, he had a Food and Drug Administration-registered marketable product, landing him in a Newsweek special issue, America’s 50 Greatest Disruptors: Visionaries Who Are Changing the World. The following year, Akhtar moved the company west to level up the tech with surgeons at the Naval Medical Hospital San Diego and the UC San Diego medical school, where he’s now a faculty member. Then came his Shark Tank appearance in early 2024, which included the first Psyonic patient, U.S. Army Sergeant Garrett Anderson, who’d lost his hand in a roadside bombing in Iraq. “He told us that when he wears our hand, he can feel his daughter’s hand,” Akhtar says.

His pitch not only won over the judges, but also made up for his abandoned medical degree. “When my mom saw me on Shark Tank, she was pretty proud of that,” he says, laughing.

The Luke Skywalker Hand

Dale DiMassi, a 46-year-old filmmaker and Psyonic’s new creative marketing manager, was pretty much over prosthetics. Born without a right hand, he’d long adapted to the world as he was. In 2023, he was developing a documentary, Grasping Beyond, that explores how groundbreaking bionic hand technology is transforming the lives of amputees and challenging societal norms about ability, when his brother sent him a video of the Ability Hand.

Holy cow! Somebody built the Luke Skywalker hand! DiMassi remembers thinking. “It’s this picture I’ve had in my mind since I was a kid when I saw that film and thought, Someday, somebody’s gonna build that,” he says. “I hadn’t worn a prosthetic in about 30 years but was really interested in seeing the technology and meeting some of the users. But it was such a game changer, I didn’t want to just document it. I had to experience it for myself, too.”

Initially, DiMassi found a reverse learning curve. “Things that people do with two hands, I’ve learned to do with one, and then had to relearn how to do it with two,” he says. But making those adjustments—such as rebalancing his body to carry items on both sides—solved other physical issues, like posture and back strain. However, it was little gestures, like shaking his dad’s hand with his right hand, that carried the most meaning. “Just doing a proper handshake, which is something in 45 years I hadn’t been able to do.”

Maddening insurance hurdles

Prosthetics have become increasingly sophisticated and varied with the rise of microprocessors, advanced materials, and computerized designs. Yet private medical insurance often drags its feet on more state-of-the-art (and expensive) prosthetics. The retail cost of the Ability Hand plus the custom socket, fittings, and training can run $40,000 to $60,000, compared to body-powered hooks, which cost about $10,000. Despite it being covered by Medicare, the device is classified as experimental by some private insurers.

“Everything is supposed to be predicated on Medicare,” says David Rotter of David Rotter Prosthetics in Joliet, Illinois, who’s given Akhtar clinical guidance since his grad school days. “But the private sphere looks for ways to belabor and deny claims or give terrible reimbursement rates, hoping people will give up and they won’t have to pay out on these expensive claims. So there’s a devious plotline; the rationale behind it is to make money.”

Prosthetists (who craft the sockets, attach them to the Ability Hands, and train their users) often do battle for their clients. After Ketelhohn’s former insurance provider, Aetna, initially denied her claim, her prosthetists at Gillette Children’s Hospital in St. Paul, Minnesota, as well as Psyonic made a case with the exact conditions for usage.

“Insurance is often looking for the cheapest way to provide the most function,” says Ketelhohn. “If you can accomplish basic living tasks like eating, dressing, and bathing with a low-cost device, why should insurance pay for an expensive new one?” Moreover, approvals rely heavily on precedent when there are none without using the requested device, thus setting up a bureaucratic catch-22. “For many activity-specific prostheses, how can you know you would use it if you can’t even try the activity?”

Insurance covered a nonfunctional cosmetic hand for much of Pursley’s life, but deemed a bionic hand medically unnecessary because she didn’t have a history of problems from overusing one side of her body to compensate. “I was actually told being able to feed and dress myself was enough,” she says. By then, Pursley was in her early thirties, married to a Marine, and covered by his military insurance, Tricare. When she began having pain and muscle strain a few years later, she tried again. This time, Tricare did cover both the hand and subsequent repairs. But it took her needing physical therapy for her shoulder and documenting her overuse issues.

“A common barrier to insurance coverage is proving that a limb difference is causing additional medical problems because of your limb difference,” she says. “Just the fact that you have a limb difference may not be considered enough need to be able to have a prosthetic. I had to prove I was breaking down in order to get this approved. Ideally, we want access to this technology before we have problems.”

DiMassi, too, endured a maddening odyssey getting coverage for his Ability Hand. After paying Anthem Blue Cross of California his preapproved $3,000 portion, the insurance company reassessed and blindsided him with a surprise bill for $9,000, which he had to resolve through the state attorney general’s office.

“You’re completely at the mercy of the insurance companies,” he says. The Ability Hand is not a normal ask, “so there aren’t a whole lot of things to benchmark it against. It often takes multiple denials and resubmitting the claim to get approval. It feels like a game the insurance companies are playing.”

The National Association for the Advancement of Orthotics and Prosthetics (NAAOP), Amputee Coalition, and So Every Body Can Move advocacy initiatives, along with injured veterans, have pushed for better insurance coverage and legislation giving people with disabilities greater access to mobility and independence. “With war, there’s always renewed interest in prosthetics because you have young, healthy veterans coming back with real needs,” Rotter says. “We are seeing a steady movement for choices available for amputees and whether they’re actually going to be covered.”

The NAAOP is currently investigating how the newly passed 2025 budget reconciliation bill, aka the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” will threaten orthotics and prosthetics coverage once Medicaid cuts and stricter enrollment provisions kick in. The Congressional Budget Office already projects some 17 million Americans will lose healthcare or subsidies over the next decade.

“This will impact orthotics and prosthetics in some way, whether it’s direct or downstream from losing access to preventive care,” says 2025 NAAOP Breece Fellow Annika Berlin, who works at Psyonic as a user experience specialist. (The 23-year-old was also part of last year’s Comic-Con crew, as Mad Max’s Furiosa.)

Rural regions are expected to be hit the hardest, especially in states that expanded their Medicaid programs—federal and state-funded health insurance for those with low incomes and disabilities—after the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010. “That’s where Medicaid dependence and amputation rates are typically higher, due to factors like limited access to preventive care, high rates of diabetes and peripheral artery disease, and occupational hazards in industries like farming and manufacturing,” she adds, noting a potential snowball effect.

Berlin has also spent years tussling with insurance companies, enduring three denied claims from Cigna Healthcare, Blue Cross Blue Shield of New York, and Aetna for other myoelectric brands. Aetna finally reversed course on her Ability Hand in 2020, her senior year of high school, after copious doctors’ notes and pain documentation from overusing her other arm.

“They’re not usually super keen on paying for the most advanced, expensive, bionic hand up front at first, even though I knew that was really important for my needs,” Berlin says. “They tend to define medical necessity as the basic ability to perform tasks required to survive—not the broader activities that allow someone to thrive, participate fully in society, and live a fulfilling, joyful life in a way that’s free from discrimination.”

For its part, last year Psyonic started the Ability Fund, a fundraising partnership with Range of Motion to raise money for prosthetics and clinical services for those who can’t afford them. Range of Motion’s network of clinicians and Psyonic will supply sockets and hands, fittings, and training at significantly reduced costs. Every $25,000 raised will enable an upper-limb prosthetic for a user in America and a leg prosthetic for one in Ecuador, which would normally retail for $100,000 to $150,000 collectively. The Fund’s first recipient is Ivan Krastev, an 18-year-old born with one hand. Already skilled in robotics and high-speed drone piloting, Krastev is heading to aviation school to become the world’s first bionic pilot.

Akhtar also wants to partner with video games that feature prosthetic-wearing avatars to create Psyonic-branded in-game purchases and use those proceeds to help defray costs for those in need.

Changing the narrative

As they head back to Comic-Con next week, it’s against this backdrop that bionic Belles and Bo Peeps serve a kind of celebratory activism by whimsically showcasing how such technological advances not only enable more fulfilling lives for those with limb differences but also change the narrative on people’s perceptions about disability.

This year, Pursley will unveil a matching red bedazzled prosthetic and ruby slippers as Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz. Her arsenal also includes a “glass” arm for Cinderella, a golden hand for Belle, an arm laced with Fabergé egg-style designs for Anastasia’s Russian princess, and a metal hand for the Sorceress from the tabletop game Cult of the Deep, whose creators tapped Pursley to help develop a character with a magical prosthetic hand. In addition to Psyonic’s panel, Pursley will appear on “Cos-Ability: Cosplay Without Boundaries” on July 26.

Meanwhile, Ketelhohn is heading back with two costumes: Astrid from How to Train Your Dragon—“It was the first movie I saw as a kid that accurately portrayed prosthetics,” she says—and the Winter Soldier, aka Bucky Barnes, a Marvel character with a cybernetic arm. “My costume looks really accurate with this hand,” she adds.

Joining them are Psyonic digital media specialist Ryan Goodwin and newcomers Krastev and Jamie Groshong, a 20-year-old San Diego State University junior who was an aspiring baseball player before losing his hand in a fireworks accident two years ago. Thanks to the Ability Hand, he’s resumed playing the sport for fun, recently hitting the first bionic home run and throwing an honorary first pitch at a San Francisco Giants game.

“The whole conversation changes with this hand,” says DiMassi. “People are beyond the ‘What happened to you?’ Now it’s ‘This is so cool. How does it work?’ Imagine the impact this is going to have on a young kid growing up and how different their experience navigating the world is going to be.”

Two years ago, Akhtar returned to Ecuador to deliver the latest version of the Ability Hand to Juan Suquillo. “It was an incredible moment because everything started with him and that trip,” says Akhtar, especially when Suquillo surprised him by turning down a hand color matching his skin tone.

“He preferred the bionic-looking version,” Akhtar says. “He said when he walks down the street, he feels like Robocop.”

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

![Øyunn finds "New Life" in latest single [Music Video]](https://earmilk.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/oyunn-800x379.png)